Richard Halliburton was an outlandish character for the 1930s. He packed his round-the-world adventures with unconventional and flamboyant antics, then retold them in his bestselling books. In the era between the two World Wars, he seemed unrelatable, which may be why his whimsical adventures were so hugely popular. Eventually, Halliburton vanished during his most daring adventure of all, an event that turned his fame into legend.

Richard Halliburton was the most famous travel writer of the 1930s, but his final adventure aboard a traditional Chinese junk ended fatally.

Raised by well-off parents in Memphis, Tennessee, Halliburton and his younger brother Wesley enjoyed a privileged childhood. They traveled interstate to visit friends and relatives — not common at that time — and attended private school. Halliburton went on to study at Princeton.

When Wesley passed away suddenly in 1917 of suspected rheumatic fever, he was just a youngster. The event catapulted Richard’s vivacious character into overdrive, and he began a life of adventure outside the traditions of an affluent upbringing.

In those days, it was expected that someone of Halliburton’s stock would enjoy a conventional life of marriage, career, and then “common death in bed”. For him, this was entirely undesirable. Instead, he wished to be “remembered as the most-traveled man who had ever lived.”

He dashed off to Europe, momentarily quenching a nascent thirst for adventure. He returned to finish his studies and gathered experience in editing, writing, and public speaking at Princeton. His adolescent lust for adventure, which he never seemed to grow out of, seeded his first great project.

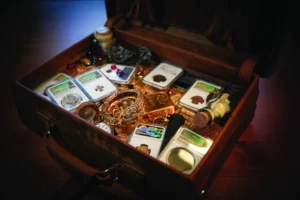

From 1921 to 1923, he explored more of Europe, Asia, and the South Pacific, making a point of doing — you might say performing — what might entertain a future audience.

On Lake Geneva, he swam to the dungeon window of Chillon Castle and was jailed for taking forbidden photos. He swam in the Nile, climbed Mt. Fuji and the Matterhorn. He managed to pack more into one trip than many can in one lifetime, even today.

Upon his return to the U.S., he desperately tried to put his adventures into a first book, but the words didn’t come easily. Eventually, two years later, he published The Royal Road to Romance, which some say is his best book. It sat on the bestseller lists for three years and was translated into 15 languages. Thereafter he was virtually unstoppable.

In his lifetime, he penned six books. His second, The Glorious Adventure, came out in 1927 and detailed his passage around the Mediterranean in the footsteps of Ulysses, the legendary Greek hero whose journey was obstructed by the sea god Poseidon.

He next headed to Mexico and Central America, where he dived to the bottom of the Mayan Well of Death and swam 90km down the Panama Canal, which he detailed in his 1929 book, New Worlds to Conquer.

Richard Halliburton spent 18 months circumnavigating the globe in his own biplane.

By this time, his escalating fame allowed him to buy a Boeing Stearman biplane which he named The Flying Carpet. He spent 18 months circumnavigating the world, covering 54,100km and visiting 34 countries. He swam in Venice’s Grand Canal and bought and sold slaves in an African village, among other unusual activities. Needless to say, these figured in his next book, dubbed suitably enough, The Flying Carpet.

As his escapades became increasingly wild, so too did his popularity. He followed each book with a schedule of lectures, where he vividly recounted his peculiar journeys.

But his character was not authentic. He carefully edited himself into a vibrant and bubbly persona for his audience. In personal letters to his family, the truth was revealed.

He suffered long bouts of depression and spoke of poor health and self-doubt. Although he wrote of the girlfriends he’d had and his pursuit of beautiful women, he was shielding his family from what was then shameful: He was gay. In 1935, French police stated that Halliburton frequented a known homosexual area of Paris and was known in specialized establishments. It also emerged that he may have been in a relationship with the journalist Paul Mooney.

Halliburton and Mooney met in 1930, at the time when Halliburton brought his plane. They’d lived together during The Flying Carpet adventures and on his fatal final adventure.

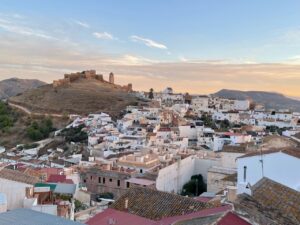

In late 1938, Halliburton and Mooney went to Hong Kong. Their intention was to build and sail a traditional Chinese junk across the Pacific Ocean to San Francisco.

They spent six weeks modifying the junk to Halliburton’s specifications. They named it Sea Dragon because of the artwork emblazoned across its stern. The pair were then joined by 12 crew members.

Concerned that his fame was in decline, Halliburton had told his cousin in 1938 that the voyage was intended to renew public interest in him. After a sail lasting an estimated three months, he planned to dock in San Francisco Bay, where visitors could pay an admission fee to the Sea Dragon.

The junk was, however, laden with flaws. Some problems had surfaced during an earlier trial run, but Halliburton was undeterred. They set off in early March 1939. They had been at sea for three weeks when a typhoon struck. Radio contact recorded the junk battling high seas, but nothing alarming was relayed. But by March 24, Halliburton and his crew seemed to have vanished without a trace and were presumed dead. Neither their remains or the wreck of the Sea Dragon has ever been recovered.

An empty grave serves as a memorial to a legend who vanished without a trace.

Halliburton’s writing was not to everyone’s liking. Some found him to be “too much”, and even Vanity Fair archly listed him as a celebrity “we nominate for oblivion.” But he was more than a flashy writer who went out of his way to be outrageous. He created fantasy during the Great Depression and pioneered adventure travel as we know it today.