The humans who cast their eyes to far horizons and then set out to reach them are a special breed. It takes enormous physical and emotional fortitude to be an explorer.

But what about spiritual fortitude? When your life comprises vast, empty landscapes and long periods of solitude punctuated by occasional violence, what price is paid? And what happens when those spiritual reserves start to run dry?

This is the question we must ask about Old Bill Williams: a man of the cloth turned man of fur, gunpowder, and steel, a skilled linguist, scout, and trapper. His intelligence was matched only by his increasingly noteworthy love of drink and predilection toward violence.

West of Missouri in the early 1800s, there was no shortage of either.

Williams blazed many paths for others, but the one he chose for his own life ended in blood-spattered snow high in the southern Rockies. Had he been blessed with the ability to look forward and see that outcome, would Old Bill have still made the same choices?

St. Louis’s siren song

It can be difficult for contemporary travelers to understand what a siren song St. Louis, Missouri, once held. Now often a stopover on road trips elsewhere, the city once represented the end of predictable life and the beginning of adventure on the frontier.

So it was for Williams, who found himself here at the age of seven. The Williams family was originally North Carolinian by way of Wales, with Bill’s father Joseph homesteading a 111-hectare plot on the banks of Horse Creek. The grant was in return for seven years of service in the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War. Doubtless, Joseph passed some of his warrior’s skills on to Bill, who developed quite a reputation as a skilled fighter later in life.

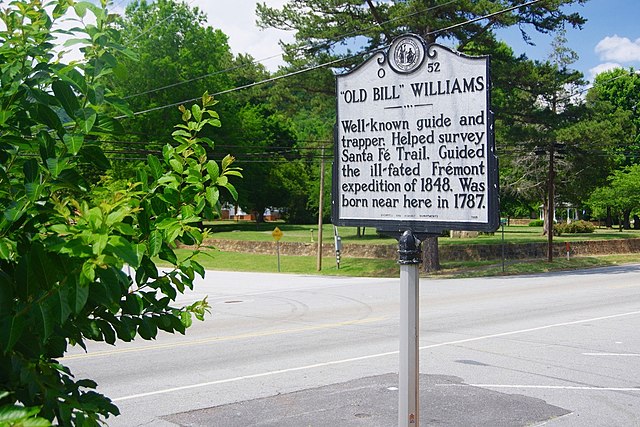

A historical marker near Old Bill Williams’ birthplace in North Carolina. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

But as a seven-year-old freshly relocated to America’s western gateway, Bill was more interested in rambling through the woods, trapping animals, and learning languages — a skill he had an affinity for.

Becomes a preacher

At 17, Bill decided to put this talent to use by becoming a traveling Baptist preacher. The year was 1804. Not much is known of Bill’s career as a minister. One can only imagine what the area’s residents — a potent blend of hardy farmers, dreaming businessmen, rough-and-tumble trappers, and Native Americans — must have thought of a fresh-faced, red-haired, verse-quoting, earnest young man preaching the good word in their midst.

In any case, Bill’s career as a Bible toter lasted seven years. During this time, his life became increasingly intertwined with that of the Osage people, a tribe native to the area. If Bill ever told anyone why he gave up his spiritual calling in 1811, that record is lost to history. What is known is that by 1813, Bill was living among the Osage, generating income via the fur trade, and working as an Indian agent. The Osage knew him as “Lone Elk” and “Red-Headed Shooter.”

Treaties, trails, and trials

Williams used his time with the Osage well. He picked up the language quickly, just one of many native tongues he learned over his lifetime. The burgeoning scout even created the first Osage language dictionary and translated the Bible into Osage as well.

He also met an Osage woman named A-Ci’n-Ga (Wind Blossom). After a period of traditional Osage courtship, he married her. They had two daughters between 1814 and 1816. Had life been less tragic for Williams, he might have lived out the rest of his days in relative domestic bliss while trapping and trading among the Osage.

But destiny had other things in store. Wind Blossom died somewhere between 1819 and 1825. Heartbroken, Williams sent his children to a boarding school in Kentucky. The eldest, Mary Ann, married a future Confederate Army captain named John Allen Mathews. After Mary Ann’s death in 1843, Mathews married the younger Williams sister.

Over the next few years, and following a pattern that generations of adventurous, itchy-footed, or heartbroken North Americans also followed, Williams found himself drawn inexorably West.

A statue of Old Bill Williams in his namesake town, Williams, Arizona. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Sante Fe Trail

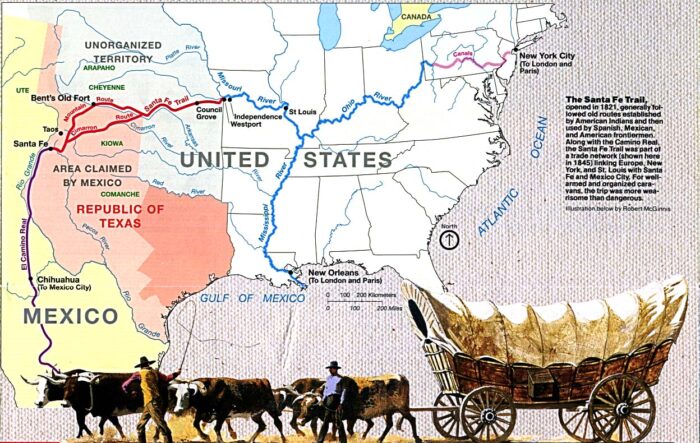

As a scout and explorer, Old Bill has two major claims to fame. The first is his involvement with the Santa Fe Trail — a perilous 1,400km trading route stretching from Franklin, Missouri to Santa Fe, New Mexico. The route had long existed among the native tribes in the region, but Williams was part of the team of European explorers that surveyed it with wagons and (eventually) with a railroad in mind.

The trail helped multiple waves of westward-traveling European pioneers as they sought land, fame, and fortune in the years of Manifest Destiny — to the eventual harm of the Native Americans along the route.

In this phase, Williams still reached for diplomacy before his firearm. His contributions to the survey included brokering several peace treaties with local tribes and translating. But shortly after this period, historians lose the thread of his life. Provable facts about his activities over the next decade are hard to chase down, but several historians note that primary sources indicate he was involved in several native massacres in the Southwest and, later, California.

A map of the Santa Fe Trail. Map: National Park Service

An entirely different man

Conflicting sources claim he both befriended and was an enemy of the Ute people — something to remember, given how Williams met his end in the San Juan Mountains of southern Colorado.

Other sources indicate that Old Bill increasingly turned to alcohol during this time and that his personal hygiene and general mood also deteriorated. It’s a long fall from enthusiastic 17-year-old traveling preacher to buckskin-clad, filthy, perpetually drunk, violent fur trapper. The question remains whether this descent happened quickly because of heartbreak and the loneliness of frontier life or by degrees, where each violent act felt necessary at the time. Maybe the booze was an attempt to soothe a weary conscience.

Whatever the cause, it seems clear that by 1840, the 53-year-old Williams was an entirely different man from the clear-eyed Missouri boy of decades earlier. Zebulon Pike, for whom Pike’s Peak is named, described him thusly:

About six-feet-one, gaunt, red-headed, with a hard weather-beaten face, marked deeply with smallpox…a shrewd, acute, original man, and far from illiterate…the bravest and most fearless mountaineer of them all.

Fremont’s Fourth Expedition

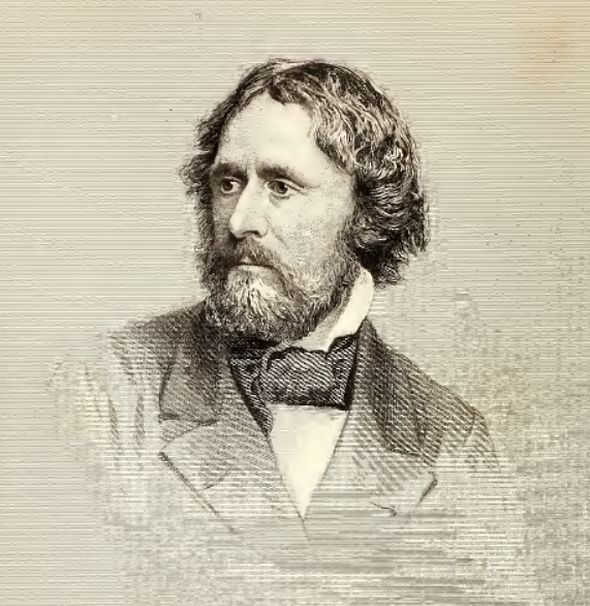

Old Bill’s second claim to fame was his association with the ill-fated Fourth Expedition of John C. Fremont.

In 1848, Fremont hired Old Bill to help blaze a railroad route through the southern Rockies. Fremont and Williams had a mutual acquaintance in Kit Carson. By then, Fremont had achieved notoriety for his participation in native massacres in California.

One hesitates to imagine what the two discussed around campfires in the evenings, especially if the whiskey was flowing.

But while conflict with natives would eventually spell the tragic end of both the expedition and Williams’ life, the famously problematic weather of the Rockies caused the beginning of the end.

An engraving of John C. Fremont. Illustration: Wikimedia Commons

Disaster strikes

Already late October by the time Fremont began his expedition, the 35-man party was deep in the Rockies come late fall. Most sources indicate that Williams advised Fremont against pushing forward along his proposed route, though Fremont later blamed Williams for the blunder. Whoever was responsible, what is known is that by November, the expedition was struggling in bitter cold, deep snow, and impassible passes. One source claims it took the party 90 minutes to progress 300 meters through the ferocious conditions.

By the first of the year, Fremont finally saw reason and changed routes, heading for Taos. Before the party made it, 11 men had died, and some were eaten by the survivors. Williams took control of the push toward safety. Without his efforts, it seems clear that many others — perhaps even Fremont himself — might have perished.

Fremont abandoned the venture after resting in Taos. He headed back to California, where he passes from this tale (but still managed to live an adventurous and complicated life).

But Old Bill Williams had one last journey in mind, and it is up to you to decide whether it absolves him of his past sins or is an example of karmic debt coming due.

Apparently without direct orders to do so, in March of 1849, Williams set out back along the expedition path in search of lost gear and possible survivors who had become separated from the group. Another expedition member, Dr. Benjamin Kern, tagged along with him.

The two men found neither gear nor survivors.

Instead, they were killed by members of the Ute tribe for trespassing on Ute territory.

Subtle shifts of character

Old Bill Williams never achieved the level of fame enjoyed by other towering examples of the American fur-trapping era. Men like Fremont, Carson, and Jim Bridger were simply more gregarious, better at self-publicity, and with reputations and exploits more suitable for an adventure-hungry reading public.

Moreover, it is hard to deny that after his wife’s death, Williams was more interested in lonely explorations of high deserts and snow-capped mountains than in politics (like Fremont) or the settled life of a trader/farmer (like Bridger).

But Williams remains a striking character nonetheless. So many mountain men of the era spring from the pages of the past fully formed. They leave home, they have adventures, and they quickly become the men whose exploits echo through history, for good or ill.

With Old Bill Williams, we can at least partially trace the subtle shifts of character as the crucible of the American West formed him from minister to mountain man over the course of a turbulent and ultimately tragic existence.

The lives of some historical figures seem purpose-made for learning lessons and drawing moral conclusions.

Other lives simply are — like mountains, they are neither good nor evil. They just rise from the plains and, for a time, stand out against the open sky.