In January 1973, 10 students from the Kuibyshev Aviation Institute embarked on a ski trek across the Lovozero Tundra in Russia’s far north, an area known for its harsh beauty and unpredictable weather. The students aimed to cover 50km from Revda to Kirovsk, over the Chivruay Pass. However, the excursion became one of the deadliest hiking tragedies in Soviet history.

The Lovozero Tundra lies on the Kola Peninsula, one of the largest peninsulas in Europe. It lies entirely inside the Arctic Circle, bordered by the Barents Sea to the north and the White Sea to the east-southeast. The western part of the Kola Peninsula has two mountain ranges: the Khibiny Mountains and the Lovozero Mountains. Chivruay Pass lies in the Lovozero range.

The Kola Peninsula. The red square marks the site of the 1973 tragedy. Photo: Dyatlopass.com

The team

The group was a mix of eager freshmen and a few graduates, all part of a tourism group from the Kuibyshev Aviation Institute (now the Samara State Aerospace University) in the Volga Federal District of Russia.

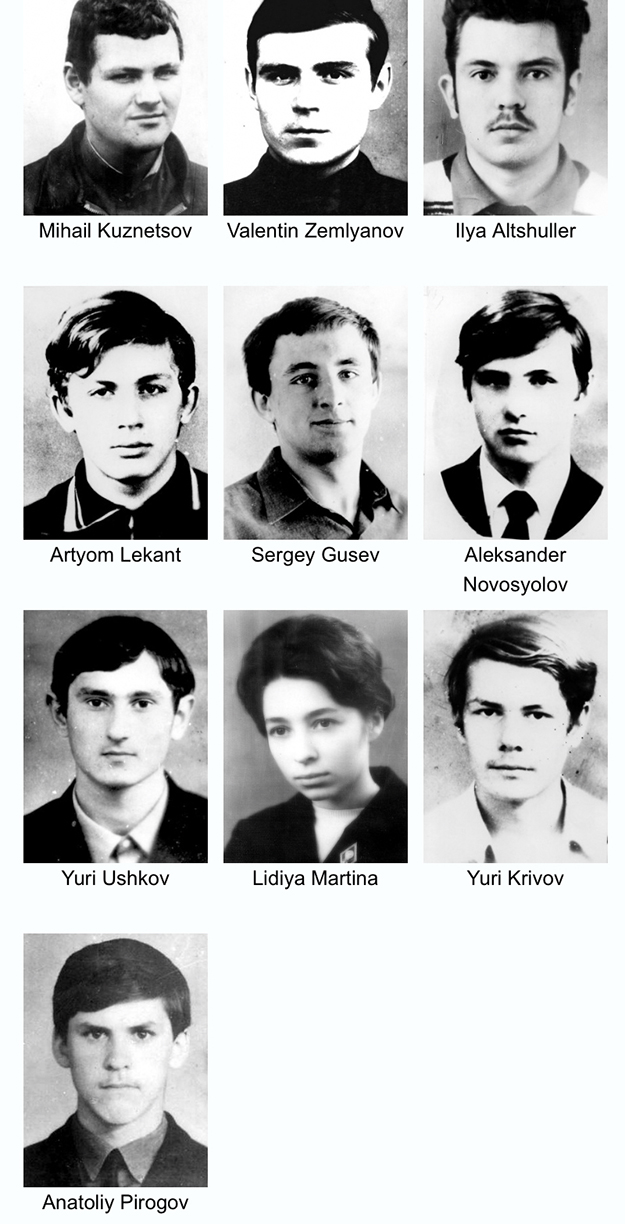

Twenty-four-year-old Mikhail Kuznetsov led the team. A seasoned skier, he had trekked the Kola Peninsula the previous year. His group included Lidiya Martina, 26, an engineer and the only woman; Sergey Gusev and Yuri Krivov, both 17; graduate Valentin Zemlyanov, 23; the group’s photographer Ilya Altshuller, 23; Alexander Novosyolov; Anatoly Pirogov, 17; Yury Ushkov, 18; and Artyom Lekant, 17. The group bonded during training hikes in the Khibiny Mountains.

The team’s goal was to complete a category II route, a challenging but achievable trek for prepared hikers. They wanted to test their skills and see the northern lights over the Chivruay Pass.

The 1973 team. Photo: Dyatlovpass.com

Setting out

On January 24, the group boarded a train from Kuibyshev (now called Samara) to Revda, a small mining town on the Kola Peninsula. When they arrived the following day, they chatted with locals. Mine worker Lev Gugel warned them of a brewing storm, with winds strong enough to “make dogs fly.” Ignoring the warning, they skied over the Elmorayok Pass that day and camped near the river under clear skies.

Their planned route would take them along Lake Seydozero, up the steep Chivruay Gorge, over the 800m-high pass, and down to the city of Kirovsk by January 31 to meet a rescue checkpoint deadline. The group’s leader, Kuznetsov, stung by a 1972 trek that triggered a costly search, was determined to finish on time.

January 26 started cold, -24°C with light winds. The team skied past Lake Seydozero and stopped for lunch in a pine grove at the Chivruay Gorge’s mouth. After lunch, they pressed on despite gathering clouds, driven by the deadline. The 700m ascent was hard, with 45° slopes slick with ice. By 3 pm, as daylight faded in the short Arctic winter, the team reached the pass’s flat plateau. Winds surged, and snow slashed visibility. Meteorological logs from a nearby settlement recorded gusts up to 110kph, with temperatures dropping to -28°C, according to SGPress.ru.

The last photo of Kuznetsov’s team. Photo: Vladimir Borzenkov via Dyatlovpass.com

The storm

On the plateau, the group tried to pitch their lightweight Zdarsky tent, but the storm ripped it apart. The ropes snapped, and the stakes pulled free in the gale.

The hikers split up. It was a common tactic to find shelter without risking everyone. Kuznetsov stayed with Gusev, Krivov, Novosyolov, and Pirogov, wrapping the collapsed tent around them for warmth. Zemlyanov led Altshuller and another hiker down the steep Kitkuay River path, while Martina and Novosyolov tried the Kuftuay River route. Tracks later showed that the scouts lost their skis, possibly blown away, and struggled back uphill in blinding snow. Hypothermia set in, and some hikers stripped off clothes, a symptom called paradoxical undressing, where the freezing brain misreads cold as heat.

By January 27, all 10 members of the team were dead. Their watches froze between 4:33 am and 5:00 am, marking their final moments. Kuznetsov’s group lay huddled under the tent, faces pressed close for warmth. A search team found Martina and Novosyolov 300m away, half-buried near boulders, clothes in disarray. Zemlyanov and his partner lay 80m apart in the Kitkuay Gorge, as if reaching for each other. Altshuller, the photographer, was 150m downslope, face down, and his watch was still ticking when he was found, months later.

The storm’s ferocity left no chance for survival without shelter.

Rescue efforts and search

Just a day later, on January 28, a Moscow Aviation Institute team, led by Viktor Samodelov, found the tent while conducting their own expedition in the area. “They looked asleep,” Samodelov told Rambler.ru, shaken by the sight. He radioed for help, but blizzards grounded rescue helicopters.

On February 2, volunteer Dr. Vladimir Borzenkov joined the search effort, and they airlifted the first five bodies to Kirovsk city. The autopsies confirmed hypothermia and frostbite, but no major injuries. According to Borzenkov’s account, reddish skin stains on Altshuller were a freezing effect, not blood.

Searches continued into June. They found Zemlyanov and another hiker in February, Martina and Novosyolov in March, and Altshuller in June (though his camera was missing).

Military helicopters, snowshoe teams, and dogs scoured the tundra. Metal detectors searched the drifts, and the teams turned up scattered gear: a notebook marked “KuAI” and sleeping bags caught on rocks. The search spanned three phases, with a cabin built on the plateau for the rescuers. Because Altshuller’s camera — possibly holding clues — had not been found, it fueled speculation about what had happened.

A representation of the first five bodies. Leader Kuznetsov had his hands up trying to hold the tent against the wind. Image: Vladimir Borzenkov

The official report

The investigation, launched quickly, blamed hypothermia from an unexpected cyclone. The group’s choice to climb at dusk, ignoring Gugel’s warning, was fatal. Kuznetsov’s push to avoid another rescue likely drove the decision, according to A. Lukoyanov’s report. The files were sealed or lost, a common Soviet practice to avoid bad press.

Borzenkov dismissed rumors of military tests or meteors, citing weather logs and no blast marks. “It was just the storm,” he told Dyatlovpass.com, noting the watches’ synchronized stoppage confirmed the timeline.

Military personnel from Kirovsk searched for the hikers, and authorities expressed their condolences. Kuznetsov and Novosyolov’s parents were barred from conducting a private investigation.

Mirroring the Dyatlov Pass incident

The 1973 Chivruay Pass tragedy mirrors the 1959 Dyatlov Pass incident, where nine hikers died in odd circumstances. Both involved storms, hypothermia, and unanswered questions, but Chivruay’s scale was larger. Families noted heavy coffins and hidden bruises, hinting at secrets.

According to Rambler.ru, Soviet officials hushed the case to protect the tourism industry and banned public memorials. Relatives pushed for files but found none, sealed for 75 years or destroyed. Theories of explosions or KGB cover-ups persist, but Borzenkov insists that nature alone caused the accident.

Tent and the first five bodies the day after the tragedy, on January 28, 1973. Photo: Vladimir Borzenko on Dyatlovpass.com

Human mistakes

Lukoyanov’s report calls it “youthful recklessness.” The group was young and uneven, mostly teens led by a 24-year-old. Wet clothes from humidity, a flimsy tent, and a dusk ascent worsened their odds, according to Borzenkov.

Kuznetsov’s 1972 near-miss may have influenced his decision-making. Splitting up scattered their strength; Altshuller’s lone climb back suggests a desperate bid to regroup. Lukoyanov notes 83 ski deaths from 1975-1990, with 12% freezing because of poor planning and ignored warnings.

The hikers (except one) were buried in Kuibyshev’s Rubezhnoye Cemetery, with a monument honoring their names. A plaque was placed on Chivruay Pass. The institute tightened safety rules, adding mentors and gear checks.

The Chivruay tragedy remains another enigmatic incident, alongside the 1959 Dyatlov Pass disaster, where nine hikers died in mysterious circumstances — with signs of panic and strange injuries — and the 1993 Khamar-Daban incident, where six hikers perished from hypothermia and exhaustion in bizarre conditions.