Two weeks ago, Riccardo Selvatico, a photographer with an Italian-Pakistani expedition on K2, found the mummified remains of a climber during a glacier walk. Russian climber Yuri Kruglov took a sample from the body to run a DNA test that will identify the deceased climber. In the meantime, the long-dead avalanche victim was buried beside the Gilkey Memorial on the glacier.

A photograph of the remains shows clothing from the Russian brand BASK, founded in 1992. In a letter sent to Planet Mountain, BASK explained that the logo style on the clothing only began in 2002.

The clothing from the body, found on K2 this month. Photo: Yousef Al-Nassar

Left: BASK logo 1995-2002. Right: BASK logo since 2002. Photo: Valentyn Sypavin via Elena Laletina

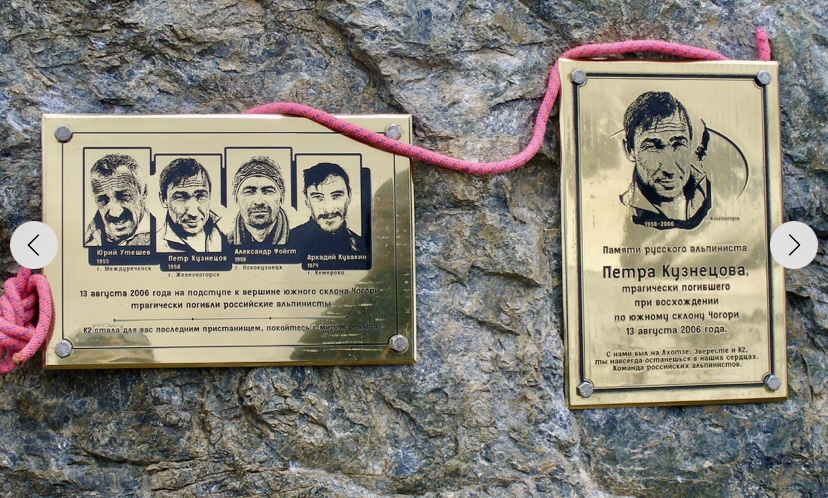

Could it be Arkady Kuvakin?

In time, the DNA test will identify the deceased climber. The current hypothesis is that the body belongs to Arkady Kuvakin.

Kuvakin disappeared along with three other Russian climbers in August 2006. A huge avalanche hit the climbers above the Bottleneck at 8,350m.

Elena Laletina of Russian Climb first suggested that the body could be one of the 2006 team. However, Laletina also told us that there is room for doubt. The body has long hair, which does not match any of the 2006 victims. According to Yousef Al-Nassar, who recently left K2 Base Camp, the body had nearly shoulder-length hair.

Laletina explained that BASK sells its gear in stores in Kathmandu too. Any climber from any country could have bought it.

Doctors who made a visual examination of the corpse thought that the body belonged to a male climber aged between 17 and 30. Kuvakin was 32 in 2006.

Arkady Kuvakin, 32, during his fatal climb of K2. The arrow indicates the BASK logo on his chest. Photo: Piotr Kuznetsov

A survivor’s opinion

Nevertheless, one of the survivors of the 2006 tragedy, Jacek Teler of Poland, told ExplorersWeb that the clothes were definitely from one of the four Russians on the 2006 expedition.

”It is a fleece sweatshirt, and during the summit push we were all in down jackets,” Teler wrote. “There are many indicators that among the leading two [Piotr Kuznetsov and Arkady Kuvakin], one of them could have already taken off his outer down jacket, or gone with it unbuttoned. It was probably one of them. Both of them had items with the BASK logo.”

The 2006 Russian team. Photo: Alexander Gaponov

The 2006 Kuzbass expedition

The four Siberians came to K2 in the summer of 2006 to climb the Abruzzi Route.

The so-called Kuzbass Expedition — named after the expedition’s mining sponsor — featured a strong team led by Yuri Uteshev. It included Alexander Foigt, Piotr Kuznetsov, Viktor Kulbachenko, Arkady Kuvakin, Alexey Rusakov, Alexander Gaponov, Sergey Naumenko, and Sergey Bogomolov.

Several other teams were on the mountain at that time. Everyone was fighting against strong winds, cloudy days, and short, unstable weather windows. Progress was slow, and it was difficult to establish camps and fix ropes along the Abruzzi Spur.

Small groups, bad weather

The Siberian team divided into small groups. According to a report by Anna Piunova of Mountain.ru, the climbers saw the mountain clearly just once during the first week of the expedition.

Warm temperatures followed the initial spell of poor weather. The ice started to melt, provoking rock fall. Kuvakin reported that some missiles weighed more than 20kg. One of them wiped out their tents in Camp 1.

On July 13, Kuvakin said that it was snowing non-stop at Base Camp. He added that, according to the meteorologists, the wind reached 150kmph at 6,500m.

Tents from other expeditions were swept off the southeast spur. During the second half of July, almost all the camps were destroyed. Despite the ferocious weather, the Russian continued working on the route. They climbed up and down, rotating their small groups and retreating to Base Camp when required.

Terence Bannon from Northern Ireland and Jacek Teler from Poland joined the Russian team for the ascent. Photo: BBC News and Wspinanie.pl

Some teams abandoned their climbs, while others continued. Three climbers even summited despite the conditions. Those descending commented on the strange sounds they heard when they stepped on the snow.

Meanwhile, at Camp 2 (6,700m), the Russians had to wait out a storm for six days.

More climbers join the group

Jacek Teler from Poland, Gia Tortladze from Georgia (who later left for Base Camp before the summit push), and Terence Bannon of Northern Ireland joined the Russians on a summit push.

The party agreed that if the weather did not improve, they would abandon their attempt on August 13.

But that day, the morning was bright and clear. Already on their summit push, the climbers decided to continue. Though some had left Base Camp two weeks earlier, the team remained strong.

Kulbachenko and Gaponov led the way, followed by a group composed of Voigt, Uteshev, Kuvakin, and Kuznetsov. A third small party of Bogomolov, Teler, and Bannon followed.

K2, 2006. Photo: Kuzbass Expedition

The silent monster

The groups kept some distance apart and reached the upper section of K2 on August 13 at about 1 pm. Suddenly, above the Bottleneck at 8,350m, a huge, silent avalanche hit them.

“We were very close to our goal,” Bogomolov recalled in an interview for Sportexpress. “The summit was already clearly visible. Two more hours of climbing [remained]. There were only 200m left when the avalanche struck us.

Bogomolov explained that an enormous piece of frozen snow and ice, 120 by 80 meters in size, hit them at high speed.

“There were none of the usual sounds,” Bogomolov said. “It all happened almost silently.”

Kulbachenko and Gaponov managed to dig themselves out, but the avalanche swept away the second party (Kuznetsov, Kuvakin, Foigt, and Utsehev). The third group (Bogomolov, Teler, and Bannon) miraculously survived.

K2, 2006. Photo: Kuzbass Expedition via Alexander Gaponov

A fruitless search

The survivors started to search for the four missing men. They could see traces of the avalanche as low as 7,800m. Bogomolov went one hundred meters below the Cesen Route, using the fixed ropes from a Japanese expedition, but without any luck. Kuznetsov, Kuvakin, Foigt, and Uteshev had disappeared.

“We had a fantastic team. Maybe the strongest Russian team at that time,” Bogomolov said.

The last photo of Piotr Kuznetsov. Photo: Alexander Gaponov

Two days after the accident, the bad news arrived in Russia. That day, Alyona Kuznetsova, Piotr Kuznetsov’s wife, was driving home from work when the expedition doctor called and told her nervously there were problems.

Alyona Kuznetsova hadn’t even known her husband planned to climb K2, thinking he was only scouting the mountain. Kuznetsov just told her about the plan by satellite phone the night before the tragedy.

Alyona Kuznetsova at K2 Base Camp in 2007, one year after the tragedy. Photo: Pravmir.ru

Some months later, Alyona Kuznetsova learned that a group would go to K2 Base Camp that summer to pay homage to the missing climbers. Kuznetsova was no mountaineer but decided that she would train and go along. She needed answers. She asked Julia, a daughter from her husband’s first marriage, to go with her.

In 2007, Alyona and Julia went to K2, with Alyona climbing to 6,200m. There, tears and anger took over. She shouted at K2: Why did it take her love away? But she finally found peace and could return to Russia, having faced the mountain.

Julia, daughter of Piotr Kuznetsov, left, and Alyona Kuznetsova at K2 Base Camp in 2007. Photo: Alyona Kuznetsova via Pravmir.ru

Kazakhs find a camera

Four years after the accident, some Kazakhstan climbers found a jacket, a backpack, and a camera on the glacier between Base Camp and Advanced Base Camp. The belongings lay at the base of the couloir where the Cesen route starts.

They left the items on the glacier but took the flash card from the Sony camera. Later in Almaty, they reviewed the photos. The camera had belonged to Kuznetsov. There were many images, right up to the hour before the accident.

In 2021, Ukrainian climber Valentyn Sypavin found a jacket on the glacier, also sporting the BASK logo.

Three years ago, Valentyn Sypavin found a jacket on the glacier at the foot of K2. Photo: Valentyn Sypavin via Elena Laletina

At the Gilkey Memorial. Photo: Alyona Kuznetsova