The ladies are basically everywhere. Media worldwide couldn’t just resist to the allure of their humble, traditional attire and homely aspect, contrasted with their ice-axes and crampons against a background of ragged summits and broken glaciers. The self-named Cholitas (a local, and not necessarily praising, name for indigenous populations in the Andes) escaladoras (that is, climbers) were a trending topic all last week, after Reuters released the news that the women had successfully climbed Aconcagua (6,962m) in their skirts and shawls in late January.

Bolivian Cholitas escaladoras on the summit of Aconcagua. Photo: Cholitas’ FaceBook

Sadly, Cholitas was apparently identification enough for most news sites, which forgot to mention the summiters’ actual names: Lidia Huayllas, Dora Magueño, Ana Lía Gonzáles, Cecilia Llusco and Elena Quispe Tincutas. Their accomplishment was acclaimed by Bolivia’s Ministry of Cultures and even by their country’s president, Evo Morales, who sang their praises over Twitter:

“Very happy about the feat achieved by our five sisters. They’re a pride for Bolivia, congratulations!”

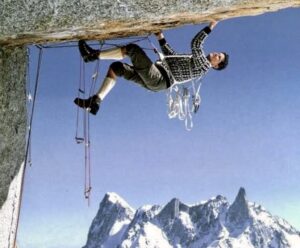

These new national heroines are part of a group of 16 Aymara women between 25 and 50. Some are already grandmothers. Originally, they worked as cooks and base camp personnel for international expeditions who came to climb the high Andean peaks. The women started climbing despite a great deal of skepticism, including from their families. They ignored critics who said that women shouldn’t climb. (Hey, this is rural Bolivia.) Instead of giving up, they went up Huayna Potosí (6,088m).

“I would always see the tourists coming down with that huge smile on their faces,” said Lidia Huayllas. “From that moment, I resolved that I would climb up too, to find out what it was that caused them so much joy.” Six peaks later, Huayllas and her mates know well what’s in a summit: freedom. “Up there, I feel free of everything,” they explained in the video below, about their story and motivations.

Recently, back at home in la Paz and slightly overwhelmed at the attention, they addressed the inevitable question: Would they be going for Everest? “It would be a dream,” summiter Analía Gonzales replied. “But that’s a much more technical and difficult peak than Aconcagua.”

The five Cholitas escaladoras at a celebratory event. On the left is Virginia Siñani, the first woman who summited Illimani peak in 1979.

In fact, the Cholitas’ approach to mountaineering is developing gradually and rather sensibly. Born at altitude, they have been climbing Bolivia’s nevados [higher peaks] since 2015, each one slightly taller, or a bit steeper, that the previous one. They began with Huayna Potosí and proceeded to Bolivia’s highest: Sajama de Oruro (6,542m). Before each climb, they perform the Challa, a thanksgiving ritual to the Pachamama, Mother Earth — considered a living being by the Aymaras. They also drank a tea of coca leaves for energy. “It’s as much a part of our culture as our traditional pollera (skirt),” Huayllas explained.

The garb isn’t a pr gimmick: Aymara women always dress in a long pollera, a woolen shawl and a too-small bowler hat, even in daily life.

Cholitas on the lower slopes of Aconcagua. Photo: Tato Varela

Before considering the Himalaya, they are planning in the near future to climb Ojos del Salado (6,891m), on the Chilean-Argentinean border. If successful, they will go further afield, to the French Alps to take on Mont Blanc.

Afraid your backpack is not technical enough for your weekend jaunts? Think again. Here are Cholitas’ Aconcagua bundles. Photo: Tato Varela

Whatever they decide, they might have already reached a summit higher than Everest, as a role model for women in their local community. Cholitas are those who dared to look up from the barren altiplano towards higher summits, while keeping their roots well grounded in the Pachamama.