There was a golden period between the early 1960s and late 1970s when British mountaineers sat atop the pile. Brown, Whillans, Haston, Scott, Boardman, Tasker — the names roll off the tongue. Chris Bonington, while perhaps not as gifted, was the best known. Now well into his eighties, Bonington still commands prime time at mountaineering events around the globe, and among a certain generation in the UK, he remains a household name.

Born into a broken family in London in 1934, Bonington had adventure sewn into his DNA. His great grandfather purportedly protected the famous Australian outlaw, Ned Kelly. After an initial foray into the Welsh mountains — including a close call in an avalanche — Bonington began climbing in earnest in 1951 at a small sandstone outcrop called Harrison’s Rocks, in the south of England. Of his first climb, he once wrote, “I knew I had found a pursuit I loved, that my body and temperament seemed designed for it.”

Over the next decade, under the mentorship of such luminaries as Hamish Macinnes and Don Whillans, Bonington rose to the upper echelons of the British climbing scene. By the late 1950s, he was making his mark in the Alps. Standout climbs in those early years included the first British ascent of the North Face of the Eiger in 1962, and the first ascent of the Central Pillar of Freney on Mont Blanc a year earlier. Coincidentally, a young Doug Scott had been on the summit of Mont Blanc that year and later recalled the significance of the climb:

“Just as we arrived on the summit, all kinds of rockets were going off…the next thing, there’s Don Whillans waddling up in the snow followed by Chris. They’d just made the first ascent of the Freney Pillar. All the fireworks had been let off because the helicopter people had thought it was the French who had made the first ascent, but Chris and the others had beaten them to it.”

Bonington at the bivouac below the Difficult Crack on the North Face of the Eiger. Photo: Chris Bonington Picture Library

Encouraged by those early triumphs, Bonington decided to leave behind a decidedly average stint as a tank commander in the British Army and become a full-time climber and photojournalist. He filled the 1960s with an impressive string of climbs, such as the first ascent of the Central Towers of Paine in Patagonia with the irrepressible Don Whillans.

But the decade was marked by the tragic death of his three-year-old son Conrad, who drowned in a friend’s garden in 1966. Tragedy later also marred his professional life, when friends such as Ian Clough and Mick Burke perished during expeditions with Bonington to Annapurna and Everest, respectively.

Arguably Bonington’s greatest strength was his expedition leadership. He didn’t think of himself as a natural leader but fell into this position by default, since his climbing partners preferred to let him do the organizing. One of his first major triumphs in this role was the first ascent of the South Face of Annapurna in 1970. World-class objectives such as this monstrous 3,700m wall — equivalent to four alpine faces stacked vertically on top of one another — were still for the taking in the 1970s.

Five years later, in 1975, the media-savvy Bonington persuaded Barclays Bank to fund the Southwest Face of Everest. He had already attempted this route unsuccessfully in 1972. But as with Annapurna, the 1975 endeavour succeeded, with Doug Scott and Dougal Haston summiting. Drama ensued as the pair famously spent a night in a snow cave at 28,750 feet — the highest bivouac ever recorded.

Bonington on Annapurna in 1970. Photo: Chris Bonington Picture Library

Remarkably, the Everest expedition was also a commercial success. At the time, climbing was largely a dirtbag sport, and Bonington faced criticism for his large and commercially successful ventures that were dubbed the Bonington Expedition Circus.

Not that this phased him out. He once said, “I’ve had stacks of brickbats and piss-takes over the years, none of which have done me any real harm, and which I have to accept as the price of success.”

In the late 1970s, Bonington moved away from logistically complex, siege-style expeditions in favour of the new alpine-style approach. The most memorable of these, and perhaps the third crowning expedition of his career, after Annapurna and Everest, was the first ascent of the Ogre (7,285m) in 1977 with Doug Scott. It also turned into one of mountaineering’s great survival stories. On the descent, Doug Scott broke both legs near the summit and had to crawl miles downslope to safety. Bonington escaped comparatively easily with smashed ribs and pneumonia.

The intervening 40+ years of Bonington’s life have included fronting television programs, penning many more books (he’s published 17 in all), receiving a knighthood for his services to mountaineering, a lifetime achievement award from the Piolet d’Or, finally topping out on Everest (then the oldest to do so at age 50 in 1985) and sought-after first ascents of mountains such as Shivling West and Kongur.

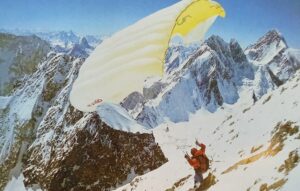

Baintha Brakk (commonly known as the Ogre). Photo: Chris Bonington Picture Library

Bonington faced the biggest challenge of his life when his first wife, Wendy, died from motor neuron disease in 2014. As so often in his life, he turned to climbing for solace, repeating his 1966 new route on a sea stack in Scotland at age 80.

Now 85 and re-married to the former wife of the late British climber Ian McNaught-Davis, Bonington is still in rude health. He speaks frequently at mountaineering events and festivals around the world and walks the mountains around his home in the Lake District of England.

A statement that Bonington himself recently made perhaps summarizes his remarkable career best: “Of all the climbs that I’ve done in the greater ranges, Everest was the only one that wasn’t a new route. Everything else has either been a first ascent of a peak, or a new route on a peak that has already been climbed.”

His legacy deserves a place at the high table in the history of mountaineering.