Shortly after nightfall, we gathered around a fireplace inside a small thatched hut. A village chief started to butcher a cassowary, which he trapped no more than a few hours before. Behind his back, I noticed bow and arrows. Traces of blood still smeared one of the arrowheads. Other curious hunters came to gaze at us.

To us, they’re exotic, but we’re even more so to them. This place, forgotten by the world, lies on the border between Western and Sandaun provinces in Papua New Guinea. Between us and the nearest road, as the crow flies, layover 250km of primary rainforest, which we had to cross on foot.

My partner, Karolina Gawonicz, is also my fiancee. This was neither our first expedition nor our first time in New Guinea. In 2015, we crossed the Arfak Mountains in West Papua, searching for birds of paradise. A couple of years later, we spent a month in the Himalaya tracking snow leopards, then canoed the entire length of the MacKenzie River in Canada later that year. But we had always wanted to return to New Guinea and we eventually had a chance to do so.

Photo: Michal Lukaszewicz

Our first idea was to cross the island from north to south at its widest point. This fell through when we learned half-way through our preparations that a British party had just done it. Back to the drawing board. We studied the maps of western Papua New Guinea further and noticed a mountain massif that seemed to be virtually unexplored. That became our play.

The Murray River, a tributary of the Strickland, eventually flows into the Fly River. Photo: Michal Lukaszewicz

At Kiunga, the last point of call for anyone traveling north on the Fly River, we made all our final arrangements, from buying the last groceries to hiring a dugout canoe. We also recruited two locals named Kevin and Rambo. (Their actual names, sadly; they both had tribal names at birth, but once they migrated to town, the local church advised them to adopt more westernized ones; a common practice.)

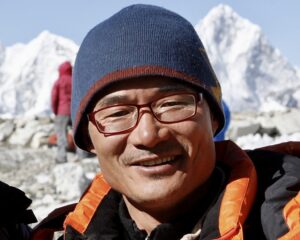

Kevin was a tall local pastor with a pigeon tattoo on his forehead and a set of impeccable teeth. Rambo, on the other hand, was less than 150cm tall. His neck featured a necklace made from wild pig’s jaws and his smile revealed his love for betel nut chewing. Although they were unfamiliar with the area ahead, they acted as translators and helped with our load over the next month.

Rambo. Photo: Michal Lukaszewicz

With more than 800 languages, Papua New Guinea is the most linguistically diverse country in the world. What unifies the nation is tok pisin, a Creole-based English which takes a fair amount of time to get used to.

The next morning, we loaded all our equipment into the dugout canoe. For the next 14 hours, the skipper headed up the Fly, Palmer and Black Rivers.

Karolina Gawonicz takes a sweaty break. Photo: Michal Lukaszewicz

While well-established routes exist between the city of Kiunga in the lowlands and Tabubil and Telefomin in the Star Mountains, terra incognita lay between the Fly and Strickland Rivers over the mountainous centre of the island. The last reported expedition to venture into these waters was the 1927 journey of Charles Karius and Ivan Champion, but they followed a different river and barely glimpsed the mountains to the east that we planned to cross.

We reached a point where submerged logs and rocks made progress impossible. We hopped out of the dugout and started hacking through this lowland rainforest, in the foothills of the Blucher Range. According to our maps (which dated back to the 1960s), a village lay about 40km away. We’d try to reach it.

Mud, mud, mud. Photo: Michal Lukaszewicz

At first, progress was painfully slow. We had to cut our way with machetes and were lucky to make one kilometre an hour. The hard machete work and the extremely muddy lowland rainforest forced us to stop often to catch our breath in the sticky air. I kept falling down with my massive backpack.

Between four of us, we were hauling 120kg for the month-long expedition. Half of that was food, since we had no guarantee of meeting people. Rambo claimed that food would never be a problem, since he could easily hunt with his slingshot. Unfortunately, he had zero success.

Yet the surrounding forest truly teemed with wildlife. Twenty metres above us in the canopy, we could clearly hear the male greater bird of paradise, with its fantastic plumage. On my shirt, I noticed a giant butterfly inserting its proboscis right into my armpit. It was ornithoptera goliath, the second-largest butterfly in the world.

Later, I spotted turquoise-striped ants on my trousers, and few meters ahead of me, the three-fingered footprints of a cassowary. This is the magic of New Guinea: Most of these creatures exist nowhere else. Tree kangaroos, giant echidnas and rats the size of small dogs all call this jungle home, but they are extremely shy, mostly nocturnal and so close to impossible to see.

The same, however, cannot be said about the spiders. Their giant webs dotted the jungle, and the best way for us to avoid the unpleasant feeling of a massive arachnid crawling on our faces was to walk while waving a long stick madly through the air in front of us. This worked, although after a long day we all ended up coated with a thick layer of “candy floss”.

Not in the face, please. A large orb-weaver spider. Photo: Michal Lukaszewicz

Our first camp came 10km from the drop-off point. We set up our hammocks on the bank of a dry riverbed and suspended the tarp above them. Kevin and Rambo refused to use the hammocks we’d brought for them. They preferred the more traditional style: gather leaves, cut some sticks, start a fire and sleep around it.

After a meal of rice and tinned fish, we retreated, exhausted, to the hammocks. An hour later, a thunderstorm delivered pounding rain. Soon, what had been a gentle creek by our camp turned into raging whitewater, inches away. In complete darkness, we had to move further into the forest. We’d learned that lesson the hard way.

Eventually, after nearly a week in the jungle, we managed to find the village of Aedro. All the inhabitants came out of their huts to greet us. In an incredibly hospitable gesture, they offered us one of their huts.

That same evening, piles of food flowed into our hut: sweet potatoes, taro, pumpkins, papaya and all sorts of greens. We tried to pay something for this generosity but they gave us strange looks that seemed to say, “Money is of no use to us.” Nevertheless, we eventually managed to convince them to take salt, sugar, oil and some of our surplus equipment.

Photo: Michal Lukaszewicz

When we left the village, we entered a montane rainforest for several days. We crossed a deep valley surrounded by high karst cliffs, which guarded the entrance to the plateau, from which the highest point of the Blucher Range erupted.

The unmapped village, known locally as Wagadarap. Photo: Michal Lukaszewicz

We continued north until the Murray River, where we found a village that wasn’t shown on our maps, consisting of just a few odd huts. At first, the village seemed deserted. Later, we discovered that it was inhabited by people who had never had contact with westerners. When they noticed our party, they immediately retreated to their huts.

To make it absolutely clear, they were not an “uncontacted tribe”. They knew of the outside world and they knew their neighbors. They just never had an opportunity to see westerners up close.

Kevin, right foreground, and Rambo, left foreground, help to cook a pig. Photo: Michal Lukaszewicz

That night, the chief killed a pig and prepared it in the traditional way, under hot stones and banana leaves. It was a chance for us to eat a proper meal, with protein. Our daily intake so far was 700 to 800kcal, so hunger was a constant companion. I would lose 14kg in a month.

The last leg of our expedition led us up the unnamed mountain massif, at 1,500m above sea level, leading to the Victor Emmanuel Range. The further north we got, the easier the progress became. We followed a path, and machetes became an unnecessary burden. A few thousand people inhabited these mountains. They regularly used the hilly airstrips to fly for visits to the city.

We quickly noticed the different attitudes that came with this development. Suddenly the concept of money was no longer foreign. Gone were the unspoiled forests and proudly independent, self-sustaining people. Our expedition ended after 30 days at the village of Tekin, where we boarded a chartered plane back to Kiunga.

The Milky Way under Papuan skies. Photo: Michal Lukaszewicz

Expedition Nuts and Bolts:

Expedition finances: Total cost: $10,000. Withdrawing local currency from ATMs in Tabubil was hit and miss but worked out in the end. The currency of Papua New Guinea (kina) is nicely waterproof, but to be safe, we kept the notes in Ziplocs.

Travel details: Papua New Guinea can be reached directly by air from Australia, Indonesia, Singapore and the Philippines. We arrived in Port Moresby from Cairns, Australia on AirNiugini. It’s worth noting that the baggage allowance on domestic flights is comparatively low (15kg).

From Tabubil, a road leads to the city of Kiunga. Several mini buses (PMVs) a day cover the 160km of gravel road. To get as close to the Blucher Range as possible, we hired a motorized dugout canoe in Kiunga, which lies directly on the banks of the Fly River. The best place to look for boat transport is either at the main market or in the port. There are no set prices. We agreed to cover the cost of the fuel, and the owner could sell whatever space was left in the canoe to local people interested in reaching the villages on the upper part of the Fly.

Risks and Hazards: Hostility from some tribal groups in Papua New Guinea is not unheard of. Other hazards included tropical diseases, river crossings, mudslides, venomous animals (insects, snakes, spiders) and political turmoil.

Through research, we discovered that tribal groups west of the Strickland River come from a different ethnic background and tended not to resolve conflicts with the occasional violence of the Highlanders east of the Strickland River. Still, we could not be sure that isolated groups would react to us as hospitably as they did.

Malaria mosquitoes were the most significant tropical disease threat. We used antimalarial Malarone tablets. Before leaving, we also had shots against hepatitis A and B, polio, rabies and tetanus.

Author bio:

Michal Lukaszewicz is a 28-year-old Polish-born, Scottish-bred adventurer with a passion for photography, especially wildlife photography. He originally studied finance but is now working his way through a biology degree. Meanwhile, he takes a variety of jobs in between adventures. “Whenever there’s enough money in the pot, we quit and go off,” he says. He can be found on Instagram.