On Sept. 24, 1975, Doug Scott and Dougal Haston stood on the summit of Everest after the first complete ascent of the Southwest Face, a route that had defeated every previous expedition. Led by Chris Bonington, the team used meticulous planning, over 3,200m of fixed ropes, oxygen, and a large crew of climbers and Sherpas to achieve their goal.

Everest’s Southwest Face drew attention after Nepal opened to climbers in 1950.

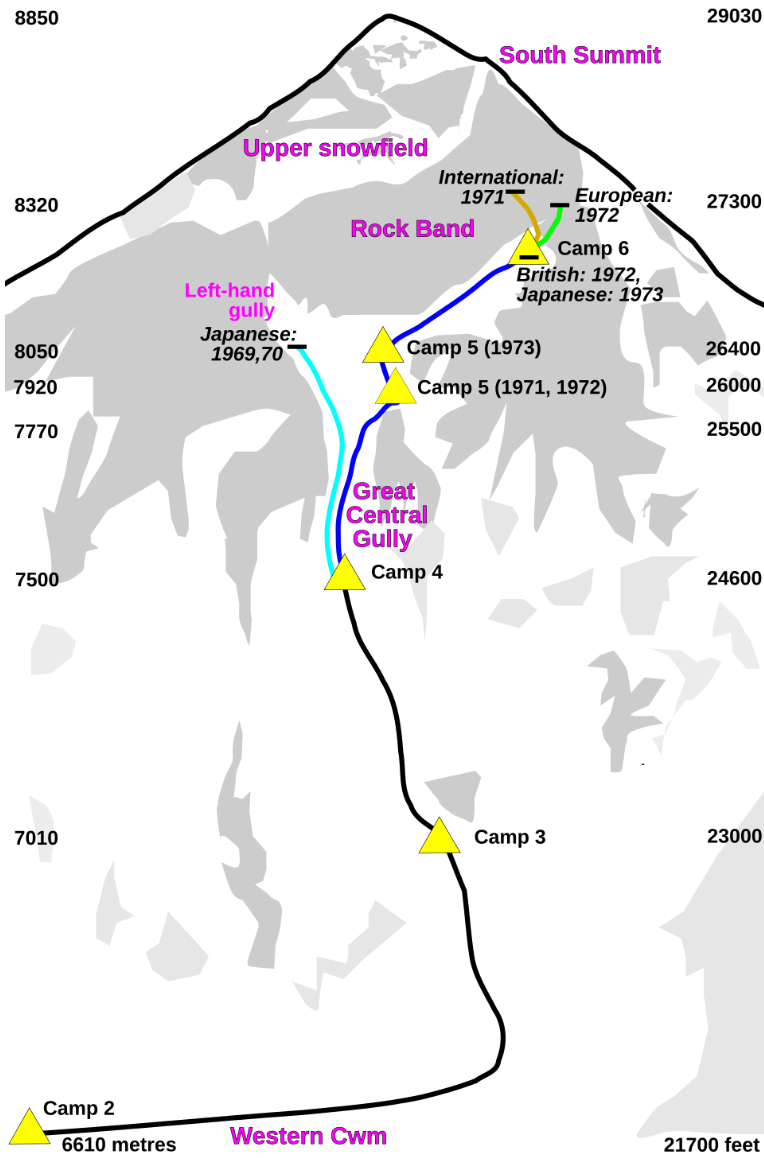

The steep, 2,000m wall of rock, ice, and snow stretches from the Western Cwm and features the Rock Band at around 8,300m, a high barrier of fractured rock and thin snow. It demands advanced climbing skills in harsh weather with avalanche risk.

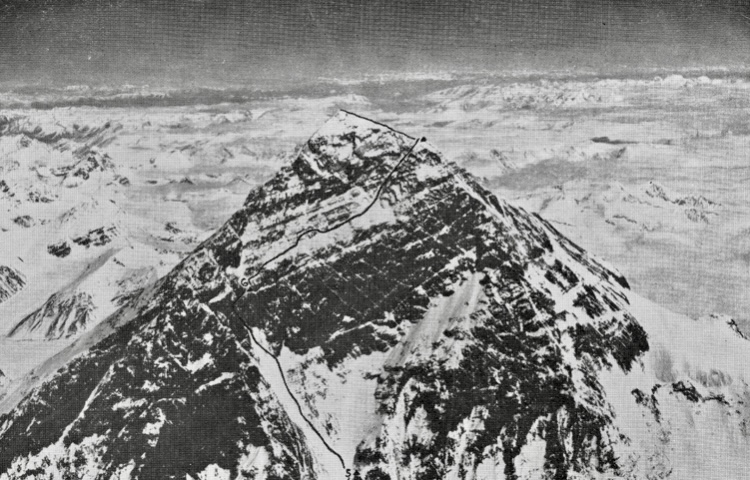

The Southwest Face of Everest. Photo: Wikimedia

Attempts before 1975

Several teams tried to climb the Southwest Face before 1975 but failed because of the route’s difficulty, brutal winds, and logistical issues.

A Japanese party led by Yoshihiro Fujita scouted the Face in the spring of 1969, reaching 6,500m. In the autumn of the same year, Hideki Miyashita led another reconnaissance expedition to around 8,000m, but the team didn’t intend to try for the summit, according to The Himalayan Database.

In the spring of 1970, Japanese leader Hiromi Ohtsuka and his large team reached 8,050m on the Southwest Face, but they finally summited via the normal South Col-Southeast Ridge route.

The 1971 spring International Everest Expedition, led by Norman Dyhrenfurth and O.M. Roberts, included climbers from multiple nations. They aimed to follow a similar route to the Japanese teams, left of the central gully. They reached 8,380m, but poor team cohesion, logistical issues, health problems, and bad weather eventually stopped them short.

In the spring of 1972, Karl. M. Herrligkoffer led a team that abandoned at 8,350m because of cold weather, low morale, and team dysfunction.

Attempts on the Southwest Face of Everest before 1975. Photo: Wikimedia

The first British attempt

In the autumn of 1972, Chris Bonington led a strong British party, including Doug Scott, Dougal Haston, and Mick Burke. They fixed ropes via the central gully, which was already a significant achievement. Brutal winds, cold, and poor supplies forced them to turn back at 8,230m, and Tony Tighe was killed in the Icefall by a falling serac.

However, this expedition laid the groundwork for their 1975 success, testing key sections of the Rock Band and learning which camp sites to use to avoid avalanches. For 1975, they planned a siege-style assault with a large team, tons of gear, and Sherpa support.

In the post-monsoon season of 1973, a Japanese expedition led by Michio Yuasa reached 8,380m but summited via the normal route.

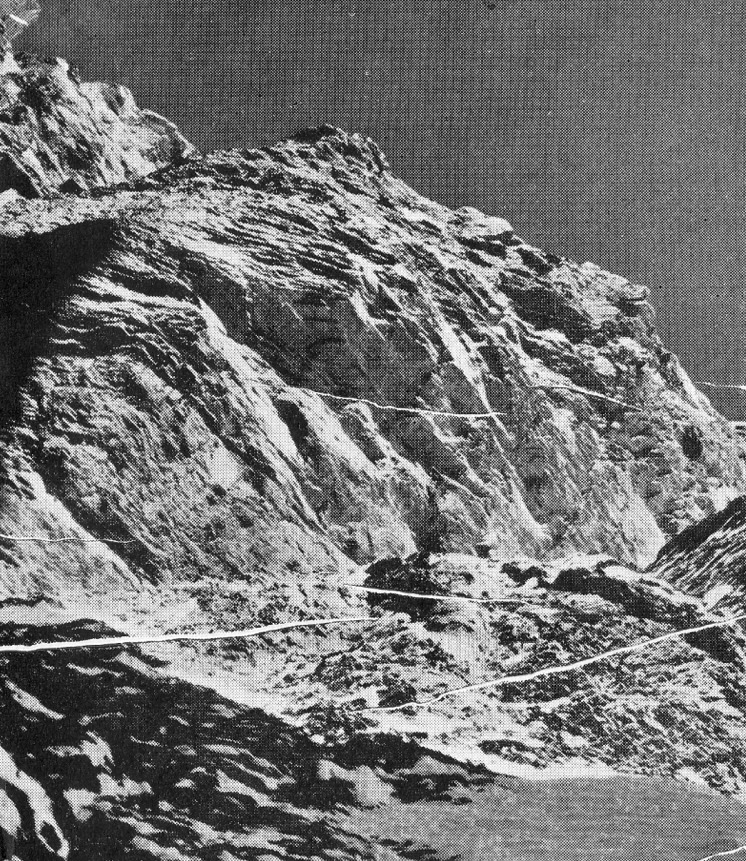

The left-hand gully leads through the notorious Rock Band into the upper snowfield. Photo: The Himalayan Club

The 1975 team

Bonington assembled a team of 18 climbers and approximately 60 Sherpas, plus other support staff. Most of the team had climbed together before 1975.

Bonington was already a Himalayan veteran. He started climbing in the Alps as a teen and led the 1970 Annapurna I South Face first ascent. A logistics master, he secured funding for the expedition from Barclays Bank and managed team dynamics.

Doug Scott was from Nottingham and began climbing at 12. A teacher by trade, he lived for the mountains. Dougal Haston, from Currie, Scotland, was a climbing star. He climbed hard alpine routes from a young age and summited Annapurna I in 1970. Mick Burke, a Manchester rock expert, filmed the ascent for the BBC. In 1970, Burke became the first Briton to climb the Nose of El Capitan. Nick Estcourt, a rock and ice specialist, was known for bold winter routes.

The 1975 route on the Southwest Face of Everest. Photo: The Himalayan Club

Pertemba Sherpa, a sirdar from Solukhumbu, led the other Sherpas carrying 40kg loads. Hamish MacInnes was the deputy leader, and the party also included Charles Clarke (doctor), a BBC crew, and logistic experts such as Mike Cheney and Adrian Gordon. The other members were Hamish MacInnes, Martin Boysen, Tut Braithwait, Arthur Chesterman, Jim Duff, Allen Fyffe, Brian Ned Kelly, Chris Ralling, Mike Rhodes, Ronnie Richards, Keith Richardson, Ian Stuart, and Mike Thompson, all from the UK. As well as Pertemba Sherpa, there were 30 more Sherpas and 26 Icefall porters.

Pertemba Sherpa, left, and Chris Bonington. Photo: Hited Nepal

The Sherpas included Mingma Nuru Sherpa, Ang Phurba Sherpa, Tenzing, Lhakpa, Nima, Psang Sherpas, and many others. Their role was very important for the team’s logistics, and Pertemba would play a starring role in the expedition.

The expedition flew to Kathmandu in July 1975. However, the journey to Everest started badly. On August 23, during the trek to Base Camp, Mingma Nuru Sherpa tragically drowned in a river.

The ascent

The team set Base Camp on August 25, and crossed the crevassed Khumbu Icefall in a day. At 6,100m, they established Advanced Base Camp in the Western Cwm and set up Camp 1 near Advanced Base Camp. They further set Camp 2 at 6,500m and Camp 3 at 6,700m at the base of the face.

Scott and Burke began to climb the face on September 6, fixing 370m of rope to a buttress for Camp 4 at 7,200m. Camp 5, at 7,700m, sat right of the central gully. Bonington moved there on September 16, staying nine days.

“I had never believed in leading an expedition from Base Camp,” he wrote in the American Alpine Journal.

Sherpas, led by Pertemba, hauled tons of gear up the mountain, including oxygen, tents, and food.

“The tremendous enthusiasm of the Sherpas who carried more, often heavier, loads…I had never thought possible,” Bonington noted. The team fixed over 3,200m of rope, with winches aiding gear hauls.

Dougal Haston on the Southwest Face. Photo: BBC

Breaking the barrier

The Rock Band at around 8,300m was the crux of the climb where past expeditions had stalled. On September 20, Estcourt and Braithwaite, supported by Bonington and Burke, cracked it. From Camp 5, they crossed a great gully to the Rock Band’s left-hand cleft.

“Although we had obtained every photograph we possibly could, none had shown what happened inside the gully; this was one of the big gambles,” recalled Bonington.

The gully was shadowed and cold, with winds around 40-60kph. A rock plastered with snow blocked the route. Braithwaite led, climbing a 60° to 70° edge with crampons and axes. He ran out of oxygen, but he kept going.

Estcourt took over above the chockstone, finding a ramp of steep snow at 8,230m. As Bonington noted, this was the key: “It was probably the hardest climbing ever attempted at that altitude.”

The ramp had an overhanging wall pushing Estcourt off balance. Without oxygen in the thin air, he climbed a pitch he called one of the hardest he had ever led. Fixed ropes secured it, and Bonington and Burke followed, hauling 300m of rope.

The group fixed 800m of rope through the Rock Band to a snowfield above. This opened the path toward Camp 6, which was set up two days later at 8,320m on a snow arete. Ang Phurba Sherpa then hauled a box tent up.

Dougal Haston near the Hillary Step. Photo: Doug Scott

The summit push

On September 22, Scott and Haston reached Camp 6. On September 23, they fixed ropes to 8,380m, battling strong winds. At dawn on September 24, they started up, using fixed ropes for speed. Haston led through rock bands and then a deep couloir.

“The snow was soft and deep, and [the couloir] looked much longer than we had expected,” Haston explained.

Haston’s oxygen failed near a rock step, and it took an hour to fix. Scott then led the step over 90 minutes, fixing a rope. The climbers waded through snow on a 60° slope, sinking to their knees. At 3 pm, they topped a cornice to the South Summit at 8,760m.

“We considered bivouacking,” Scott wrote, citing loose snow and the late hour. Yet they eventually pushed on. The Hillary Step, masked in powder, was shoveled by Haston.

Finally, on September 24 at 6 pm, Scott and Haston summited Everest, finding a Chinese marker at the top. “The view was as much and more than any climber could expect,” Haston said.

Dougal Haston during the summit bid. Photo: Doug Scott

Darkness descends

Because they topped out late, it was soon dark. The two climbers were forced to bivouac at 8,750m. Without sleeping bags and low on oxygen, this was a dangerous situation.

“The cold had worried its way into our limbs,” Scott wrote. They dug a snow cave and survived till dawn, when they descended to Camp 6.

The second push

Bonington planned three summit bids. On September 26, Martin Boysen, Pete Boardman, Mick Burke, and Pertemba Sherpa left Camp 6. The weather was not good, with strong winds and cirrus clouds that warned of changing conditions.

Halfway across the snowfield, Boysen turned back after suffering oxygen issues. Boardman and Pertemba reached the South Summit by 10:30 am. Soon after, Pertemba’s oxygen bottle iced up, and it took 90 minutes to fix. Finally, Boardman and Pertemba Sherpa summited at 1:10 pm, flying Nepal’s flag. Pertemba’s success was a Sherpa milestone on a technical route.

Tragedy

While descending, they met Burke below the summit. He was climbing solo. Boardman and Pertemba waited at the South Summit, but within half an hour, the weather dramatically deteriorated. In whiteout conditions, Boardman and Pertemba Sherpa waited an hour, then descended, barely finding the fixed ropes. “It was an agonizing decision,” Bonington recalled.

Burke vanished. Bonington noted that he was certain that Burke reached the top. Nobody knows what happened to Burke, but a cornice fall to the Kangshung Face is likely.

Boardman and Pertemba made it down, but with frostbite and snowblindness, respectively.

The team could not search for Burke until September 27 because of the storm.

The Daily Mail covered the news of the 1975 ascent. Photo: Berghaus

Aftermath

The team returned as heroes. It was the first British Everest summit, and they achieved it via the hardest route climbed at the time. The 1975 ascent was the pinnacle of siege-style expeditions. With 70 people and tons of gear, it showed what teamwork could achieve.

Bonington’s 1976 book Everest the Hard Way became a bestseller. The same year, Burke’s footage was used in a documentary titled Everest the Hard Way.

The 1975 Bonington route was successfully repeated to the summit by a Slovak party in 1988, in alpine style. However, that expedition ended in tragedy, in a story we’ll look at in depth in a future story.

You can watch Everest The Hard Way here: