The cost of human life is a thread that runs throughout the entirety of the award-winning film 109° Below. Fresh from a Best Adventure win at the 2024 Banff Mountain Film Festival, the 14-minute documentary takes viewers back in time to 1982, when an elite group of rescue climbers struggled to save two young men who became lost on New Hampshire’s Mount Washington.

Washington’s claim to fame is “the worst weather in the world” — earned thanks to record wind speeds, icy temperatures, and violent winter storms. In fact, the film is called 109° Below because that’s the temperature (in Fahrenheit) that the wind-chill factor reached while the crew was filming on Mount Washington.

Photo: Screenshot

A serious problem

“When the weather is bad, all you have to do is lose your mitten, and you’ve got a serious problem,” Paul Cormier, a member of New Hampshire’s Mountain Rescue Service, says in one of the film’s interviews.

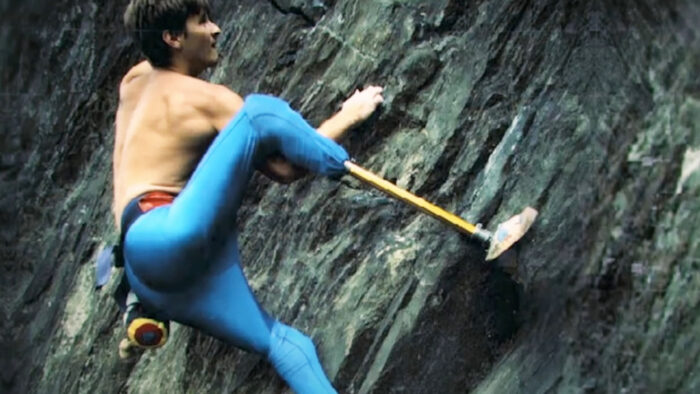

But in 1982, 17-year-old Hugh Herr and his partner Jeff Batzer did much more than lose their mittens. Although experienced for their age, the two young men made a fateful decision — to press toward Washington’s summit in the face of an oncoming storm.

Reaching a ridgeline, the pair decided to walk three more minutes closer to their goal before descending. Those three minutes proved disastrous, as visibility dropped precipitously. Herr screamed at Batzer, “Let’s get the hell out of here,” and began their descent.

Photo: Screenshot

Frostbitten and hypothermic

By the time they realized they’d taken the wrong line down a steep slope, they had neither the energy nor the time to retrace their steps. They kept descending and were quickly lost. They continued bushwhacking until two or three in the morning, then finally halted, frostbitten and hypothermic.

Meanwhile, the climbers had been reported missing, and a 10-person crew of volunteer Mountain Rescue Service members set out to find them. And then tragedy struck. While conducting the search, two of the rescuers were caught in an avalanche. One survived, but Albert Dow broke his neck in the crush of snow and debris. It was a stunning blow to the close-knit rescue community, which still had a duty to the missing climbers.

Photo: Screenshot

“I hated the people we were searching for. But I realized I hated this young man because my friend was dead,” Joe Letini, a member of that 1982 rescue team, says in the film. “But Hugh was 17. Sometimes, you just push that little too far. And you don’t know what’s too far. You’re learning. Hopefully, you learn from it.”

To learn from the experience, the two climbers had to survive it. And they almost didn’t. As the fourth day of their ordeal dawned, they began to lose hope.

“Most people believed that we were dead…we gave up all attempts to survive,” Herr says.

Accidental salvation

But in a moment of serendipity, a group of snowshoers found their tracks in the fresh snow and followed the trail to a cave where Herr and Batzer were fading fast.

Transported to a hospital, both of Herr’s legs were amputated below the knee. Batzer’s lower left leg, all the toes on his right foot, and the thumb and fingers on his right hand were amputated.

Photo: Screenshot

But the worst part for Herr? Learning the true human cost of his rescue.

“To me, that was the lowest point of my entire life. Hearing that a fellow climber had died while searching for Jeff and I,” he says.

109° Below is fast-paced, dramatic, and well-shot. It uses expertly constructed reenactment footage, gorgeous landscape videography, and interviews in a combination familiar to fans of Touching the Void. But where the film truly shines is in its final moments, when it examines the aftermath of the rescue attempt and finds some redemption for its primary subject.

Photo: Screenshot

A hard lesson learned

“Albert Dow’s death was very profound for me. It transitioned from shock into rage at myself for making bad decisions in the mountains and really putting others at risk. That rage drove me ironically to climbing again, with artificial limbs. I was going to use every cell in my body to do something positive with my life,” Herr shares.

Photo: Screenshot

Herr didn’t just climb with prosthetics; he designed them himself. He’s now a professor at MIT and a world-recognized leader in the prosthetics field.

“If I pitied myself and didn’t apply my mind and body to something good for society, I thought that would be an absolute disgrace to Albert’s sacrifice,” he concludes.