Of the 12,015 people who had summited Everest by the end of 2023, only 15 have reached the top in winter. Thirty-four expeditions have tried, including 13 without bottled oxygen. Only five of those expeditions were successful, and just one of the 15 summiters did so without oxygen. Only one person topped out alone.

Everest became the first 8,000m peak ascended in winter when Polish climbers Leszek Cichy and Krzysztof Wielicki topped out using supplemental oxygen on Feb. 17, 1980. Yet Everest’s winter climbing history is much more interesting than statistics and records. Thanks to detailed expedition reports, we can get a taste of just how hard it is to climb an 8,000m peak in winter. With Jost Kobusch making his third attempt this season, it is a good time to look at Everest’s winter history.

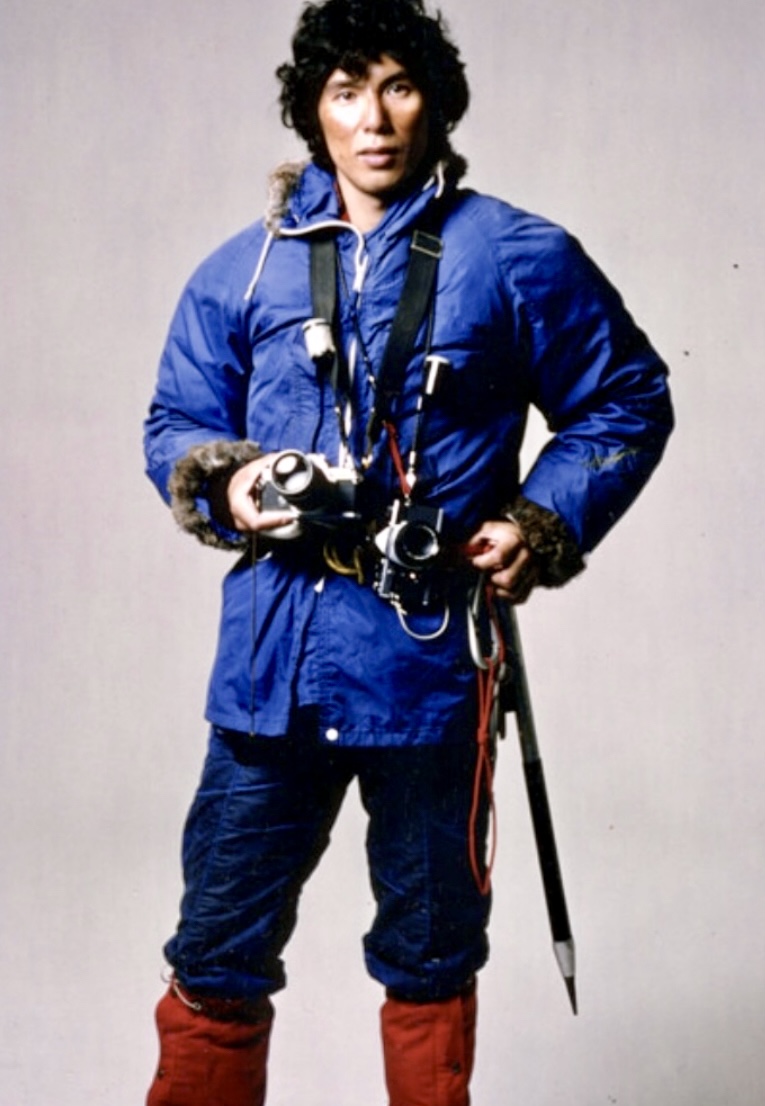

Jost Kobusch during one of his Everest winter solo attempts. Photo: Jost Kobusch

Winter beginnings

Between 1950 and 1964, all 14 of the 8,000’ers were climbed for the first time. But none of those came in winter. It took nine long years after climbers bagged the final 8,000m peak (Shisha Pangma, 1964) that climbers made it above 7,000m in winter.

On Feb. 13, 1973, Polish climbers Andrzej Zawada and Tadeusz Piotrowski summited 7,492m Noshaq, the second-highest mountain in the Hindu Kush. One year later, Zawada led a winter expedition to Lhotse. On Dec. 25, Zawada and teammate Zyga Heinrich reached 8,250m before an approaching storm forced them to retreat. During the expedition, they observed weather conditions in the Everest area. Soon after, the Poles began to think about getting a winter permit for Everest.

After a long wait, a permit finally arrived in November 1979. The Polish team chose the South Col-Southeast Ridge (normal) route. Zawada’s team included 20 Polish climbers, six hired workers above Base Camp, and climbing sherpa Pemba Norbu.

Brutal weather

According to Jozef Nyka’s report for the American Alpine Journal, the expedition arrived in Base Camp on Jan. 5, 1980. Things looked hopelessly bleak. Wild winds blew from the north, and the temperature stayed very low. High on the mountain, they observed jagged snow banners. The glacial streams froze, and melted ice was the only source of water.

The Polish Everest winter team. Photo: Andrzej Zawada

Temperatures hovered between -25ºC and -45ºC. Hurricane-strength winds pounded the mountain.

“Wind stripped the snow cover off the slopes, exposing rock and bare ice. Moving on the ice-covered stretches required double attention, extra belaying, and fixed ropes on otherwise easy sections,” they wrote.

The climbers struggled to breathe, and the icy air made them sick. In these conditions, just establishing the lower camps proved a challenge.

In the first week of February, the wind continued to destroy their camps. Again and again, the Poles rebuilt them. Camp 3 (at 7,150m) was blown away several times, and it was only on February 9 that they could progress higher.

On February 11, Leszek Cichy, Walenty Fiut, and Krzysztof Wielicki reached 7,960m. There, they set up Camp 4 on the slope below the col. The wind had not abated, reaching 200kph. During the night, the furious wind eventually pushed the climbers back to Camp 3.

Wind off, snow on

The next night, the wind dropped, and it started to snow. On February 13, Ryszard Szafirski and Zawada returned to Camp 4. The next day, they tried to progress up the Southeast Ridge, but high winds again forced them back. Szafirski and Zawada left their oxygen cylinders high on the mountain and started down to Camp 3, with Zawada moving slowly.

The normal route during the Polish winter ascent of Everest. Photo: Summitpost

Permit issues and summit push

Meanwhile, Base Camp heard that the Nepalese government wanted the expedition to finish on February 15. Thanks to a Polish official in Kathmandu, the deadline was eventually extended to February 17.

There was no time to lose. Zyga Heinrich and Pasang Norbu Sherpa set off immediately. They reached 8,300m, but a harsh snowstorm stopped them short of the summit. Heinrich and Pasang Norbu’s attempt was without bottled oxygen.

On February 16, after a night’s snowfall, the sky cleared.

Krzysztof Wielicki and Leszek Cichy reached the South Col and slept at Camp 4. In the early morning, the two climbers started their summit push and topped out on February 17 at 2:30 pm. After pausing for breath, they called Base Camp.

“Conditions are very tough. Some of the steeper sections of the ridge are free of snow with ice-covered rocks exposed. Strong winds blow all the time; it’s unimaginably cold.”

The two climbers put the Polish and Nepalese flags on top and stayed there for 40 minutes before descending.

Zyga Heinrich and Pasang Norbu Sherpa in Camp 4. Photo: Andrzej Zawada

But not everyone was happy

After this first-ever winter ascent of an 8,000’er, Italian alpinist Reinhold Messner created some controversy. As Bernadette McDonald wrote in her fantastic book Winter 8,000: Climbing The World’s Highest Mountains In The Coldest Season, Messner refused to accept the Pole’s winter ascent for two years.

Messner insisted that the Poles had not climbed in winter because Nepalese officials had recently shortened the season, choosing January 31 as the end of winter.

Messner was planning a winter expedition to Cho Oyu the following year and continued to discount the Everest winter climb for some time. McDonald writes that Miss Hawley defended the Polish claim. “I’m not among these quibblers,” Hawley said.

Though Messner later accepted the climb, he continued to claim it was illegal. Eventually, the Ministry of Tourism of Nepal issued a certificate that validated the Polish Everest winter ascent. Messner had to give up his crusade.

With the Polish success, a new chapter in 8,000m mountaineering began: the winter ascents.

Krzysztof Wielicki on the summit of Everest during the first winter ascent. Photo: Leszek Cichy

Other winter ascents on Everest

On Dec. 27, 1982, Yasuo Kato summited alone via the normal route. But Kato died on the descent.

On Dec. 16, 1983, Japanese climbers Takashi Ozaki, Noboru Yamada, and Kazunari Murakami, plus Nawang Yonden Sherpa from Nepal, topped out via the normal route.

On Dec. 22, 1987, South Korean Young-Ho Heo and Nepalese Ang Rita Sherpa summited by the normal route. Ang Rita Sherpa climbed without supplemental oxygen. To date, he is the only person to have summited winter Everest without bottled gas.

The last winter ascents came on Dec. 18, 20, and 22, in 1993. Japanese alpinists Fumiaki Goto, Hideji Nazuka, Shinsuki Ezuka, Osamu Tanabe, Ryushi Hoshino, and Yoshio Ogata climbed via the Southwest Face (the Bonington route).

Unsuccessful attempts

The 29 expeditions that unsuccessfully attempted Everest in winter turned around for a variety of reasons: dangerous conditions, high winds, extreme cold, bad weather, exhaustion, lack of oxygen, accidents, or falling rocks.

Yasuo Kato. Photo: Yasuo Kato Archive

Seven mountaineers died during winter expeditions. As mentioned, Yasuo Kato died during his descent. Other deaths were attributed to high-altitude falls at 8,800m, 8,700m, 7,500m, and 6,800m. One climber fell into a crevasse at 6,300m, and a sherpa died of AMS at 6,500m.

Other routes

As well as the normal South Col-Southeast Ridge route, there were attempts by the Southwest Face, the North Col-Northeast Ridge, the North Face (the Hornbein Couloir), the Northeast Ridge-North Face, the face between the North and Northeast Ridges, and the South Pillar-Southeast Ridge.

Jost Kobusch ascends alone in winter. Photo: Jost Kobusch

German alpinist Jost Kobusch will attempt his winter climb via the Lho La–West Ridge. It is the same route he attempted in the winter of 2019-20 when he reached 7,366m, and in the winter of 2021-2022, when he turned around at 6,450m in bad weather.

The British Winter Everest Expedition led by Alan Rouse first attempted Kobusch’s route in the winter of 1980-81. Their highest point was 7,300m in poor weather.

In the winter of 1984-85, a French-Italian-Belgian expedition led by Eric Dossin attempted the route and reached 7,500m. Again, bad weather halted the climb.

In the winter of 1985-86, a South Korean party led by Kim Ki-Heyg abandoned the same route at 7,100m in strong winds. They were exhausted with a sick team member, according to The Himalayan Database.

The late Ang Rita Sherpa is the only climber to summit Everest in winter without bottled oxygen. Photo: Shutterstock