We had never heard of Yashkuk Sar, a 6,668m peak in Pakistan’s Hunza region until Dane Steadman of the U.S. applied for a Cutting Edge Grant for an expedition there. And it was only after we saw some images and the route map that he, Cody Winckler, and August Franzen had climbed that we realized the scope of their achievement.

Dangerous and difficult

The first exceptional aspect of the climb lay in choosing a little-known peak in the remote Charpusan Valley, which had been closed to foreigners for the last 15 years.

“The locals said that a couple of teams went with the intention of climbing Yashkuk when it was open to expeditions decades ago, but ended up trying/climbing easier peaks,” Steadman told ExplorersWeb at the time. “My guess is that’s because from the north side, Yashkuk is either dangerous (seracs crown almost the whole north face) or difficult (the buttress we climbed is fairly steep and rocky).”

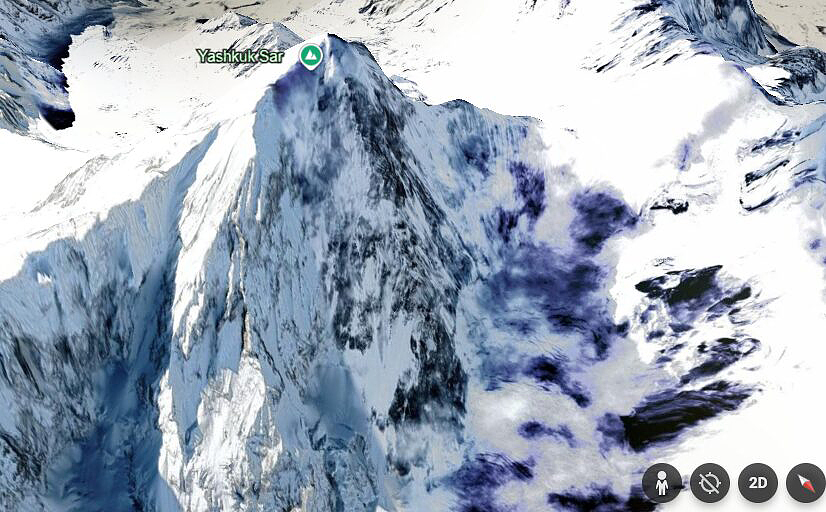

The team spotted and chose their goal on Google Earth:

Yashkuk Sar on Google Earth, with the north buttress on the right.

The team remained isolated for weeks and climbed alpine style in a single push between September 19-23. The grade of their route, called Tiger Lily Buttress, speaks for itself: AI5+ M6 A0 2,000m.

Shortly after returning, Steadman spoke with Explorersweb and on social media about the expedition.

On the summit of Yashkuk Sar. Photo: Dane Steadman

Acclimatizing

The team set up their base camp in the valley at 4,000m and prepared for a long stay and a gradual acclimatization. In the short periods of acceptable weather between rainy spells, they made a first reconnaissance to Yashkuk I and II, to a 5,300m sub-peak, and then to a 6,200m peak named Sax Sar at the head of the West Yashkuk cirque.

Sax Sar’s only ascent was from the opposite side in 1998. Climbing it required a bivouac at a col just below 6,000m. It was the highest bivy ever for the climbers. The climb and the summit views was a high point of the expedition.

“We were floating in the sky, higher than I’d ever been, at the junction of three of the great ranges of Asia,” Steadman reported. “The line we’d come to climb was beautiful. We were more psyched than we’d ever been.”

The climb

On the morning of September 18, the team left base camp with a week of high pressure in the forecast. That night, while the climbers were in their tent pitched still far from the north side of the peak, they had quite a scare.

“In the middle of the night, we were woken by a roar, and when we looked out the door, we saw an enormous avalanche raging down from the serac crown, well to the left of our route but with a rapidly spreading powder cloud,” they reported. “We held the tent up through the wind blast that followed, then tried to go back to sleep.”

On the following morning, they started the climb anyway, simul climbing and then traversing on fragile rock slabs until the night caught them. They set up their ice hammock, already 1,000m up the wall. On the second day, the team climbed 400m on moderately difficult ice to a narrow ridge, where they set up their second bivouac.

That night, just after we’d tucked in for bed, another roar echoed across the mountain. No worry, just another serac avalanche that didn’t threaten us. But we looked outside, just in case, and were horrified to see it ripping down the central ice gully we had intended to climb through the upper headwall. A snow mushroom must have released, and there were countless more like it on the headwall. Everything had seemed to be going so well, but suddenly bailing seemed likely.

We poured over photos of the wall, and eventually pieced together a possible line up the eastern prow of the headwall, safe from the mushroom sea and maybe climbable. It was worth a shot.

The team had to rappel down diagonally in order to get to the east side of the buttress. From there, an ice arete led to the base of the headwall. The next bivy was set up atop a mushroom that overhung the vertical mile of the wall.

The spectacular third bivouac. Photo: Dane Steadman

Even more difficult

On the next day, the mixed climbing got more and more difficult with each pitch until the technical crux: a gently overhung wall of shattered gneiss plastered with snow, with the whole north face sweeping below.

Above, we climbed two traversing rope lengths weaving through the forest of snow mushrooms atop the headwall, to the exit: an overhanging ice tube up to the cornice. But over the cornice wasn’t sun and easy terrain like I’d hoped, and when I pulled over the third cornice, after trenching through snow deeper than myself, I finally saw sunlight to the west, but with it came a biting wind.

The following night proved the hardest, due to the unforgiving wind at 6,500m. Luckily, the summit was really close, and the climbers stepped on the highest point of the peak at 7am on September 23.

The descent took 1,500m of rappelling and down-climbing the west and northwest faces until the bergschrund.

“We were safely back on the dry glacier as the sun set on our fifth day on the mountain,” Steadman said.

A nerve-wracking wait for news

Meanwhile, outside Pakistan, we patiently waited for news. The team’s outfitter finally announced that they had summited, but another several days went by before the team was confirmed safely down.

“Some experiences are simply so dense and too rich to fully comprehend,” August Franzen wrote on social media. “The two months spent in Pakistan with Dane Steadman and Cody Winckler was a journey that will take quite a while to process. For now, I’m content sitting with the nostalgia of an expedition that has left a mark on me in ways I can’t yet articulate and memories that feel more like dreams than reality. In many ways, my mind is still there, bivvied near the Pakistan-Afghanistan border in our shared sleeping bag among the greatest mountains on earth.”