In the 1800s, many explorers flocked to the polar regions. But another vast, uncharted land presented opposite difficulties, one that often attracted adventurers of a more spontaneous — but no less courageous — stripe.

The first British ships carrying convicts-turned-colonials arrived in Australia in 1788. Nearly 40 years later, a man named Charles Sturt arrived on Australia’s sandy shores. He was a soldier manning one of those convict ships, and somewhat adrift in his own life. Liking what he saw of the country, he decided to stay. In time, his contemporaries called him “Australia’s greatest explorer.”

Adrift on the sea of life

Charles Napier Sturt’s early life could be seen as a blueprint for the construction of a future explorer. Born in India during the British occupation, he was sent to live with relatives in England at the age of five. He attended and excelled at school, but as the eldest of 13 children, his father lacked the funds to send him to Cambridge to complete his education.

After an aunt pulled some strings, Sturt found himself assigned the rank of ensign in the British army. He saw action against the Americans in the War of 1812, apparently successfully, as he was promoted to the rank of Captain by 1825.

A portrait of Sturt in later life, painted in 1858. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Why, exactly, Sturt took a detachment from his regiment to escort convicts to Australia two years later is unclear. Perhaps he was bored with military life. Whatever the reason, when Sturt came ashore in Sydney in 1827, he immediately took a liking to the climate and the landscape.

At 32, Sturt was in the prime of his life, and the governor of New South Wales swiftly promoted him again. Now moving in rarified circles, Sturt was befriended by other great Australian explorers: John Oxley, Allan Cunningham, and Hamilton Hume, among others.

Inspired by their tales of outback adventure shared over brandy and cigars, Sturt wasted no time petitioning for his own expedition. By the next year, he was pushing into the Australian interior.

First expedition

Like many Australian transplants of his day, Sturt was obsessed with the idea of an Australian “inland sea.” This made sense to Europeans who were used to geographical features like the Mediterranean, the Caspian Sea, and the North American Great Lakes. They simply couldn’t conceive that a landmass as massive as Australia wouldn’t contain a correspondingly large body of water. As it happened, scarcity of water was a running theme during the rest of Sturt’s Australian travels.

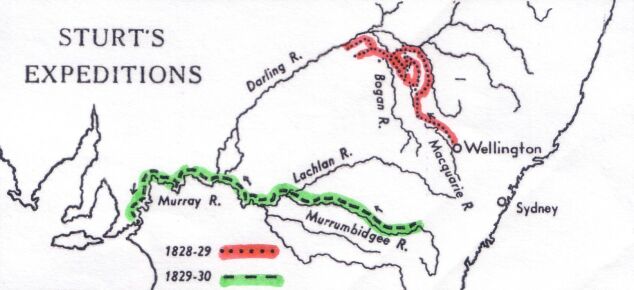

For this first expedition, Sturt was accompanied by a servant, three soldiers, and eight convicts. It’s unknown if the convicts were along for the ride willingly, but it’s safe to assume the answer is no. The party pushed into unknown country in December, following the courses of the Macquarie, Bogan, and Castlereagh Rivers.

A map of Sturt’s first two expeditions. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

They eventually reached the Darling River. (Sturt named it after the governor who had promoted him and supported his expedition.) The Darling is the third-longest river in Australia. In the coming century, it became an important travel route for Australia’s colonials.

But 1828 was a drought year, and most of the rivers the party followed were sluggish, brackish, or completely dry. Finding water on this expedition was extremely difficult. By 1829, Sturt and his men were back in Wellington Valley. Although they’d charted important waterways, Sturt was disappointed by the lack of an inland sea. He was still determined to find it.

Into the bush again

Sturt wasted no time convincing Governor Darling to approve a second expedition. The nominal goal was to determine the course of New South Wales’ westward-flowing rivers. But Sturt had an inland sea to find.

This time, the expedition carried a disassembled whaleboat. When the party reached the Murrumbidgee River in early 1830, it assembled the boat and began traveling downriver.

It was on this portion of the expedition that Sturt showed his mettle as a leader. Australia’s Indigenous people heavily populated the waterways of New South Wales, and the party clashed with them several times. Sturt proved a deft negotiator, always choosing to settle disputes with parlay instead of violence. His strategy worked — Sturt and his expeditions never resorted to armed conflict with Aborigines.

On this expedition, Sturt also gained his reputation as a leader with consummate concern for his men. This leadership style goes a long way toward explaining why adventurers continued following him into the bush, even though his expeditions tended to end in disappointment.

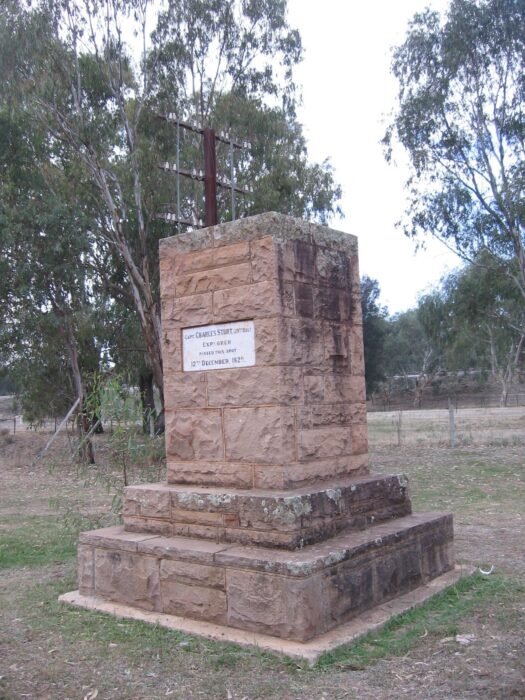

A monument to Sturt near the site where the second expedition halted from exhaustion and lack of supplies. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Disappointment

By late January, Sturt had reached the Murray River and began following it downstream until its confluence with the Darling. In February, the expedition reached the sea and came to two disappointing conclusions. One: the Murray’s swampy, sandbar-laden mouth was impassible to shipping. And two: if Australia had an inland sea, it wasn’t anywhere close.

The party now faced the daunting prospect of rowing the whaleboat upstream against the Murray and the Murrumbidgee, in the dead of the Australian summer, on short rations. It was brutal work, and it took the party nearly two months to partially retrace its steps.

At the site of modern-day Narrandera, on the banks of the Murrumbidgee, the group lost all strength. The heat, effort, and lack of nutrition had broken Sturt’s health, and the once hale 35-year-old’s vision was beginning to darken. Sturt halted the expedition and sent the two most healthy remaining men overland in search of supplies. The rescue mission was a success, and Sturt’s expedition eventually returned to Sydney with no loss of life after rowing nearly 2,900km.

But Sturt would never be the same.

Blindness, and a return to Australia

Sturt left Australia for England on sick leave in 1832. By the time he reached his home country, he was almost totally blind. His vision and some of his health gradually returned. In 1833, he published his account of his Australian adventures, Two Expeditions into the Interior of Southern Australia during the years 1828, 1829, 1830 and 1831. While the work gained him fame among Great Britain’s reading public, it did little to help his goal of further promotion in the British military. After marrying the daughter of a family friend in 1834, Sturt decided to return to Australia, this time as a farmer.

He and his wife settled on 20 square kilometers near present-day Canberra. He fit into the agrarian life nicely and even conducted a few mini-expeditions. In 1838, while driving cattle overland from Sydney to Adelaide, he proved that the Murray and a river known as the Hume were one and the same.

But Sturt never lost his dream of finding the mythical Australian inland sea. In 1844, now 49, undertook his final major expedition.

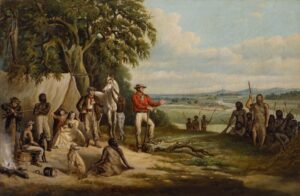

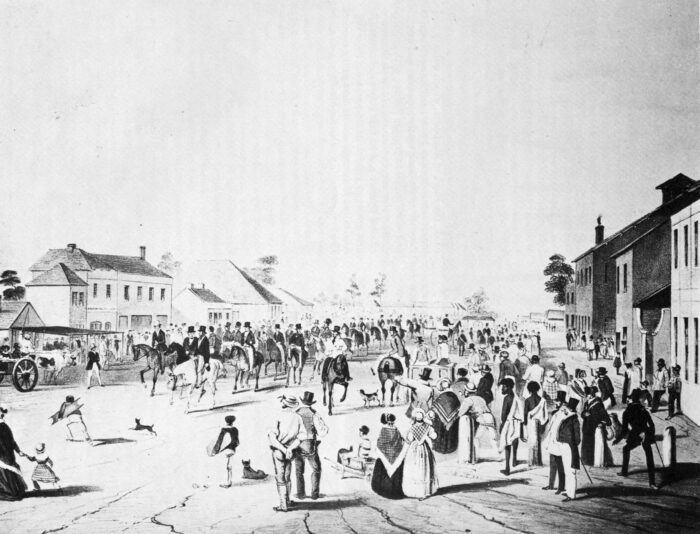

Sturt’s third expedition sets off. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Ever the optimist

For his final foray, Stuart was accompanied by 15 men, 200 sheep, six wagons, and, always the optimist, a disassembled boat. The mission was to advance into central Australia, find the inland sea — and possibly plant a flag in the middle of the continent.

But Australia’s unforgiving Simpson Desert had other plans. Despite his love for Australia, Sturt’s health just didn’t seem made for the place. Scurvy, heat, and lack of supplies took their toll, and surgeon John Harris Browne had to assume command due to Sturt’s poor condition. The expedition set out for home, eventually traveling 4,800km.

It wasn’t until 16 years later that Scotsman John McDouall Stuart planted a British flag in Australia’s center point.

A ‘born loser’?

Sturt lived out the rest of his days under the pressure of financial burdens, troubled eyesight, and intermittently poor health. He never recovered from his years of adventuring in Australia. He had political aspirations and applied for the governorships of Victoria and Queensland. But his expedition fame didn’t translate into financial security, and the powers-that-be were unwilling to appoint such a relatively poor man to such high office. His application for knighthood also languished.

Sturt’s affable nature worked against him in the political arena. As his listing in the Australian Dictionary of Biography notes:

“Indeed, his capacity for arousing and retaining affection was remarkable; it made him an ideal family man but a failure in public life. Without toughness and egocentricity to balance his poor judgment and business capacity, he had little chance of success in colonial politics. In this sphere, he might well be described as a born loser.”

Charles Sturt at age 73. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Sturt died suddenly in 1869, leaving behind his wife, two sons, and a daughter. And honestly, it’s a wonder he made it to age 74.

But where Sturt failed as a politician and businessman, he succeeded as an explorer. His name speckles the Australian map — he even has a national park named in his honor. His treatment of the men who followed him and the Indigenous people he met during his expeditions is a model that other Australian explorers would have benefited from following.

And in a final stroke of belated recognition, after his death, Queen Victoria granted his wife the title of Lady Sturt — as if her husband had been a knight all along.