Climbing is dangerous almost by definition, but an elusive red line marks the threshold of the “too risky, better turn around.” The question is, where is that line?

This changes with each climber and each situation, but we asked some of the best in the world at the latest Piolets d’Or where their red line is.

Helias Millerioux was awarded a Piolet d’Or in 2018 for his new route on the South Face of Nuptse with Frederic Degoulet and Niçois Benjamin Guigonnet. This was Millerioux’s third attempt on the peak. On a previous try in 2016, he retreated when he realized the constant falling rock and ice were “a guillotine.”

Asked about their new route on the West Face of Ama Dablam, Mykyta Balabanov and Mykhailo Fomin of Ukraine told ExplorersWeb that they went for it “because it was new, it was aesthetic, and it was safe.”

It may not be romantic, but relative safety against objective dangers is paramount for most high-level alpinists — at least for those who want to remain living alpinists. On the other hand, the Piolet jury usually considers commitment and exposure as added merits when selecting the best climbs of the year.

High stakes

Both Millerioux and Fomin were at the recent Piolets d’Or in Italy. As we pointed out in a story last week, the tributes to four excellent climbers, past recipients of the award who died this year, somewhat overshadowed the general joy. The families of Kazuya Hiraide, Kenro Nakajima, and Archil Badriashvili reminded everyone of alpinism’s high stakes.

Yet all the awarded climbs required significant commitment to uncertain success — at times, uncertain survival. We spoke informally with the awarded climbers about how they assess the dangers, the risks they are willing to take, and their personal red lines.

One of the Swiss team members on Flat Top, 2023. Photo: Matthias Gribi

Safety first, but accept risks

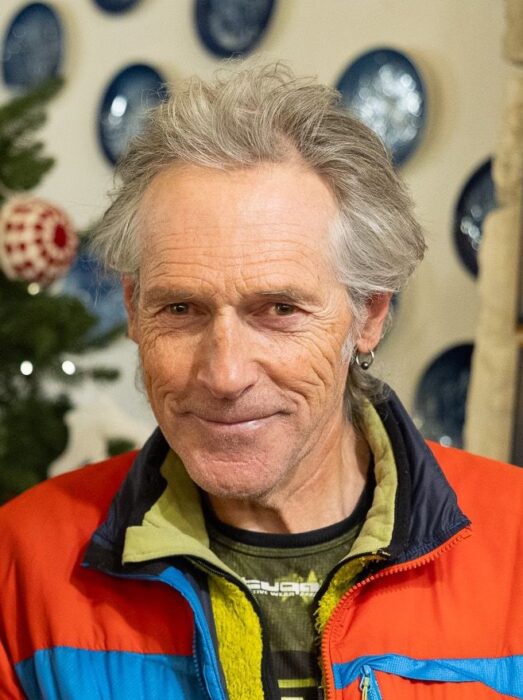

Veteran climber Jordi Corominas, awarded a Piolet d’Or for Life Achievement, has always accepted the risks involved and the potential consequences, even the most serious.

“Death is there, we all know that one day we may not make it back home, and it is something we have freely chosen,” he said.

But he also remarked that safety comes first when he teaches younger climbers and most of all, when he guides.

“Being a guide, assessing and minimizing risks is essential,” he said. “Basically, that is what your clients pay for.”

Jordi Corominas. Photo: Piotr Drozdz/Piolets d’Or

To what extent do climbers feel the pressure from sponsors and the public? Corominas and Simon Elias (a UIAGM guide based in Chamonix) conceded that some young climbers might feel compelled to take too many risks because of the idealized world of social media.

Risk-averse society

Three young climbers from Switzerland won a Piolet d’Or for an impressive line on Flat Top, a mountain in the Indian Himalaya. During their presentation, they described how for most of the climb, they didn’t know whether a route would open to the summit or whether their line would dead end.

Asked whether the current generation of climbers is more reckless than the pioneers, the youngsters said it is quite the opposite.

“Our modern society of comfort tends to delete risk from the equation in everything we do,” they said. “If anything, people are more afraid than ever.”

For risk management, the Swiss consider three elements: conditions, terrain, and the human factor.

“I try to tick at least two of these three boxes in green before starting a climb,” said one of them, Nathan Monard.

Alps vs expedition

Yet decisions that are easy to make in the Alps are harder when you only have a single weather window during a month-long expedition in the Himalaya.

“We keep the same criteria but, well, we climbers tend to push the threshold of risk further on an expedition,” said Hugo Beguin. “But going on an expedition is an extra risk in itself. We don’t have rescue teams ready to fly and help, the communications, the accessibility, etc.”

“I personally base my decision-making on how I feel,” added Matthias Rigi. “Conditions may be perfect, but If I don’t feel well during the climb, I’ll turn around.”

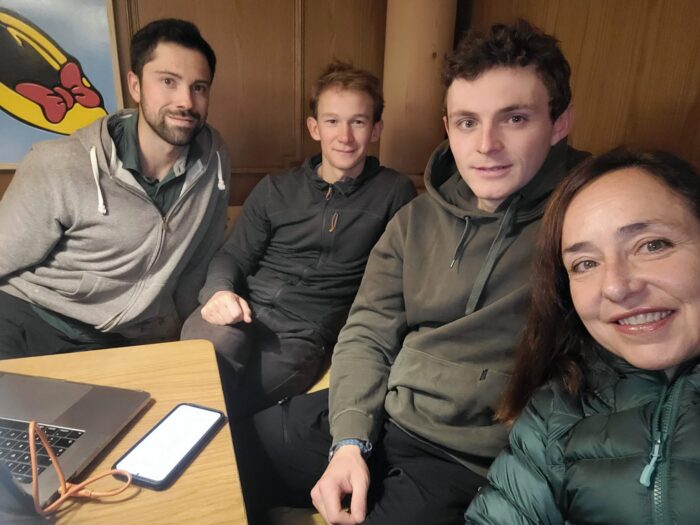

The writer with (left to right) Nathan Monard, Hugo Beguin and Matthias Gribi. Photo: Angela Benavides

About pressure from sponsors, Beguin pointed out that “Most of the time, climbers push themselves out of personal motivation.”

“In fact, it is hard to feel completely without pressure,” Gribi added. “There is always something pushing you.”

Jannu north face

Then there was the first alpine-style ascent of the mighty north face of Jannu by Americans Alan Rousseau, Matt Cornell, and Jackson Marvell. Every step up the 2,700m face was high risk. After Rousseau noticed he had frostbitten fingers some 100 vertical meters below the summit, the team agreed to continue after a brief discussion.

Marvell said that they are ready to discard a potential line or postpone a climb because of the risk of avalanches, rockfall, or dangerous weather. Cornell pointed out the team’s slow, cautious approach to Jannu. It took them three attempts to succeed. The first trip was a reconnaissance to check if climbing the face was even an option. On the second attempt, they tried a line. On the final trip, they made their choice and went for it, “ready to accept whatever comes,” they said.

Leader Alan Rousseau is an ambitious climber determined to push limits a bit at a time.

“Once on the face, I go body length by body length,” he explained. “The face is so big, it can be overwhelming, it can’t be figured out…You’ll never get anything done if you keep looking too far ahead. You focus on the three meters around you, and in the passages without protection, you don’t make a move you can’t reverse.”

Rousseau admitted that as a team, he, Marvell, and Cornell became pretty good at creating that sort of three-meter bubble and not looking beyond it when they are on unknown terrain.

Teamwork is essential on hard objectives, as (left to right) Marvell, Rousseau, and Cornell showed on the north face of Jannu. Photo: Piotr Drozdz/Piolets d’Or