In the world of mountain running, there’s Kilian Jornet, and then there’s everybody else.

That may seem like a bold statement if you’re one of those people for whom the Spaniard’s name only surfaces when he does something that breaks through niche media outlets and lands in the international news cycle. His 2017 double summit of Everest is a good example. But the fact is, Jornet is a consistent and successful pusher of human boundaries, even when he’s not tackling the world’s highest mountain.

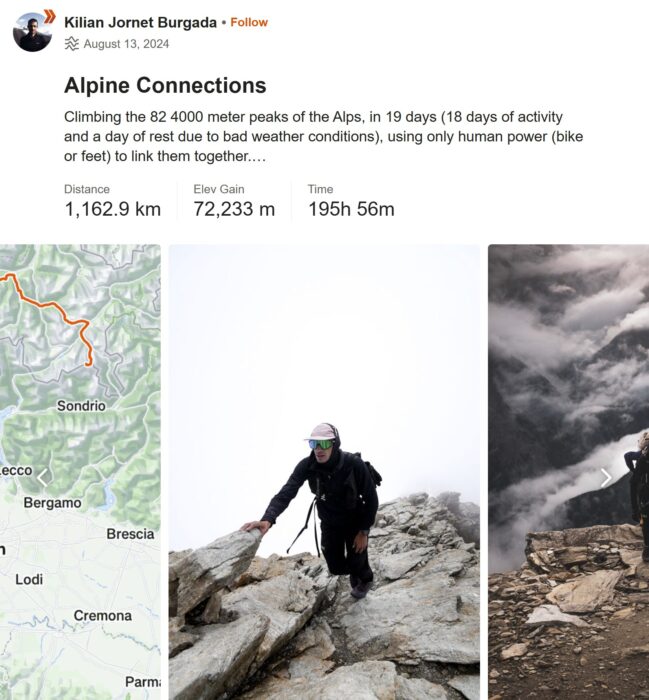

Case in point, Jornet’s August 2024 “Alpine Connections” effort. The runner determined to link up all the 4,000m+ peaks in the Alps in one continuous push, using only human-powered modes of transportation. That’s 82 peaks, 1,207km of distance traveled, and 72,233m of elevation gain over 16 stages. He climbed, ran, cycled, and sometimes trudged. Roughly 87% of his effort was on foot.

Not about a record

“To keep moving, no matter the conditions, weather, or gear I had with me, I had to push myself to the absolute limit of my knowledge and beyond to make it through. The effort was physical, technical, but above all mental, in managing stress and emotions,” the athlete wrote shortly after completing the route.

“The most difficult part of such a journey was to stay fully concentrated for so many hours a day and to lower the stress in complicated situations, to stay lucid and make good decisions.”

Photo: Strava Screenshot

19 days

That’s the sort of thing any athlete might say after completing a successful Fastest Known Time (FKT) attempt. And yes, Alpine Connections was indeed a record-breaker, besting two other famous documented attempts.

The late Swiss alpinist Ueli Steck did it in 62 days in 2015, while Italians Franz Nicolini and Diego Giovannini made a successful run in 60 days in 2008.

Jornet snagged the record in 19 days.

But Jornet, perhaps with a Spaniard’s sense of the romantic or perhaps with wisdom gained over an astoundingly successful career, was not focused on the record-breaking nature of the run — at least not in hindsight.

“I believe what I did was not important as such, but it was something that transformed me deeply,” he noted. “To speak of records would cheapen the experience I had. I was deeply inspired by Patrick Berhault’s vision, by Martin Moran and Simon Jenkins’ first link-up of 4,000’ers, by Franz and Diego’s, and Ueli’s feats.

“But although we followed similar principles, we weren’t trying to break records. Instead, we wanted to explore the Alps, linking those summits under our own power, not focusing on external performance,” Jornet continued.

Nonstop link-up

The idea for Alpine Connections came to Jornet after his 2023 Pyrenees project — a route that saw him link up 177 3,000m peaks in eight days. Jornet, who lived in the Alps for a decade, saw the potential for a similar, more ambitious project in his former home range. He studied the linkup projects of the adventurers who preceded him in Alps, reached out to friends and friends of friends, and poured over maps.

Jornet’s goal was to accomplish the feat in a way that felt “more like a long ‘non-stop’ link-up than a multi-ascent collection link-up.” The aesthetics of such a tactic are what appealed most.

His timing was strategic but not without risk. Late-season conditions made for easily visible crevasses and dry ridgelines. But those same conditions made crossing bergschrunds (the crevasse that forms when moving glacier ice separates from fixed ice) more hazardous. Rock faces were also more unstable than earlier in the year.

Jornet cycles between climbs. Photo: @nickmdanielson

Off to the races

Setting out on August 12, shortly after competing in the Sierra Zinal mountain race, Jornet began by riding his bike up to Grimsel Pass in the Bernese Alps. His first goal was the summit of Piz Bernina (4,049m). From there, it was off to the races. A host of friends joined him for different segments along the way. His longest push was 34 hours, his shortest just under four.

Whenever possible, he stayed high and slept in mountain huts or bivouacs to preserve the aesthetic integrity of the route.

This strategy only fell apart once, in stage four at Valais, when he ran down to the ski resort Saas-Fee to escape troubling weather brewing over the high peaks.

A film crew documented the effort, and according to Jornet, there “will be probably a nice film” about the project. In his blog, Jornet referenced “decisions I’m not proud of, which I need to review. [Decisions] that made me reflect on why sometimes I pushed too far, accepting some risks that I consciously find unreasonable.”

Perhaps we’ll get a better look at some of those decisions in the film.

Frantic pace, dicey conditions

But on the whole, and despite the frantic pace and dicey conditions he sometimes encountered, Jornet came out of Alpine Connections in good health. Unlike his Pyrenees link-up project, he didn’t lose any weight, and he was able to eat and rest enough to maintain his strength. Jornet is known for his flowy mountain-running style, and he reported feeling that flow on many of the ridges he tackled.

Jornet enjoying a well-earned warm drink between stages. Photo: @joelbadiavisuals

“Effort didn’t exist anymore, time stopped, my body was at one with the environment. Those are the moments I live for,” he wrote.

For Jornet, the name of his project is about more than linking up mountain peaks. It’s about the more subtle connections he made — to himself, to the people who helped him along the way, and to the landscapes he traversed.

And while not an “expedition” in the classical sense of the word, the Alpine Connections project is likely the most impressive physical feat of the year.