By the time Gunther Pluschow’s aircraft plowed into a Patagonian lake in 1931, the 44-year-old had already experienced a lifetime of adventure. The German aviator and explorer was the first to survey and film Argentina’s most famous region by air, a contribution for which the Argentinian Air Force still lauds him to this day.

But those expeditions in the late 1920s and early 1930s were just a slice of Pluschow’s dashing life. It’s a great tragedy of history to wonder what towering figures could have done if chance, fate, or whatever you want to call it had given them more time.

Pluschow spent a good deal of his short years on Earth dreaming about South America. When he finally got there, it killed him. But before it did, he left a mark on the world that stretched from Germany to Asia to America to Italy to Britain and back again.

The Aviator of Tsingtau

Gibraltar, 1915: British agents boarded a ship freshly docked from New York City. Acting on intelligence lost to history, the men searched the ship and found someone who shouldn’t have been there — a travel-worn, sharp-eyed man with a high brow and unmistakenly Teutonic features.

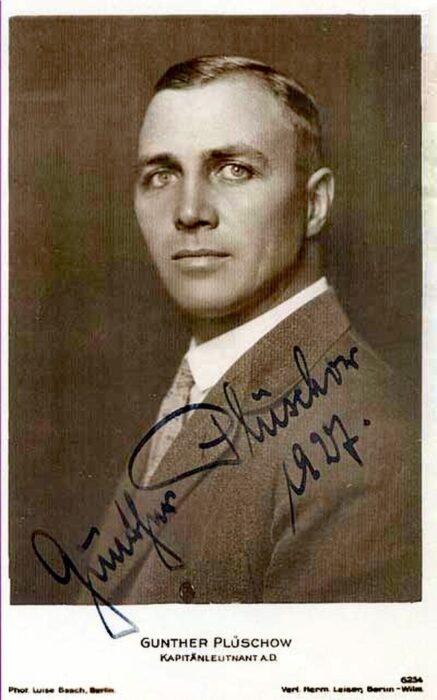

Gunther Pluschow, later in his life. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

WWI was in full swing, and the Brits promptly took the man into custody on charges of being an “enemy alien.” As they prepared to bundle him off to a prisoner-of-war camp in England, they discovered something improbable. The man in their custody — then 29-year-old Pluschow — had, in 1914, been the subject of a massive manhunt that covered two continents. The press had dubbed him The Aviator of Tsingtau.

Born in 1886, the son of a journalist, Pluschow had an unremarkable life until he enrolled in the German military. He was a man awaiting his moment. When hostilities broke out in August 1914, Pluschow was assigned to the East Asian Naval Station at Tsingtau, then part of a Chinese land concession to Germany.

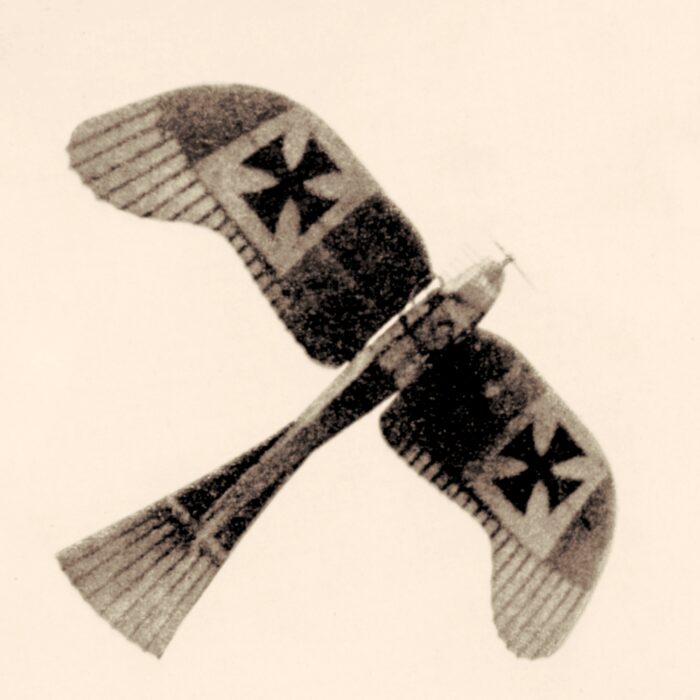

Pluschow was one of two pilots stationed there (remember, at the outbreak of the war, military aircraft strategy was in its infancy). Pluschow and his fellow pilot Friedrich Mullerskowski flew Taubes — distinctive, bird-like monoplanes that were popular before the start of the war. Unarmed except for a few bombs that pilots could manually drop, Taubes were stable but turned slowly and were easy targets.

The birdlike Taube monoplane that Pluschow flew during World War I was slow and hard to turn. But the plucky pilot made it work. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Adventures in Asia and beyond

Soon enough, Mullerskowski crashed his plane, leaving Pluschow the sole German pilot in the area against eight faster and more maneuverable Japanese aircraft. He stayed alive, which is impressive. But he also managed to shoot down one of the Japanese planes with his pistol from the air, which is astounding.

The Taube being what it was, Pluschow mostly flew observation and scouting missions. When the Japanese and British military forced the abandonment of the East Asian Naval Station, Pluschow was dispatched to Nanking with a package of secret military documents. But his much-abused aircraft wasn’t up to the journey. He crash-landed in a rice paddy 250km later, and set out for Nanking sans wings.

Traveling first on foot and then via junk (a traditional Chinese river ship), Pluschow arrived in Nanking and delivered his documents. But he soon became aware that Allied forces were watching him and moving in for an arrest. Just as they swooped in, he commandeered a passing rickshaw and fled to a train station, where, with the judicious application of a bribe, he fled to Shanghai.

In that port city, Pluschow obtained Swiss travel documents and boarded a ship first to Nagasaki, then to Honolulu, and finally, to San Francisco. He crossed America and wound up in New York City, where he considered approaching the German consulate. But Allied forces were hot on his tail, and somehow, the press got wind of his presence in New York. Obtaining illicit travel documents yet again, he boarded a ship for Gibraltar in January 1915. There, Allied forces finally caught up with him, ending an escape that had taken him nearly three-quarters of the way around the world.

Patagonia dreams

By May, the pilot found himself the resident of a prisoner-of-war camp in Leicestershire, England. But the Brits were unprepared for a man of Pluschow’s squirrely nature. Timing his escape to coincide with a major storm, the German slipped away from his captors and made his way to London, where he disguised himself as a dock worker while he waited on a handy ship on which to stow away.

Scotland Yard issued an alert for a man with a dragon tattoo on his arm — a little souvenir from Pluschow’s Asian adventures. It was at this phase of his life that Pluschow became interested in Patagonia. Holed up out of the public eye when he wasn’t scoping his escape on the docks, Pluschow read book after book about the region, no doubt dreaming of a better time when he could use his aviation skills to explore rather than wage war. That distant land must have seemed pristine and wholesome in the midst of the horrors of WWI.

The always plucky Pluschow also found some time to visit the British Museum during his layover.

Finally, he slipped aboard a ship bound for the Netherlands and eventually made it safely back to Germany. He is the only German in either World War to ever escape from a British prisoner-of-war camp. His countrymen, unable to believe that Pluschow somehow made it from China to Germany in a year-long, eastward push, promptly arrested him as a spy.

Patagonia, finally

The next few years of Pluschow’s life were sedate compared to the previous ones. Even though the war still raged and Pluschow was promoted to Lieutenant, he settled into a life of command that kept him out of harm’s way. He got married, had a son, and wrote a popular book, The Adventures of the Aviator from Tsingtau. Following the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, civil and military unrest became the normal state of affairs in the broken country. Pluschow retired from the military at the age of 33, not knowing if he’d ever fly again.

Pluschow with his son, shortly before his death. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

At loose ends at first, Pluschow eventually found work on a sailing vessel bound for South America. After making port in Valdivia, Chile, Pluschow left the ship and traveled across Chile until finally, blessedly, he reached Patagonia.

The landscape immediately captured him, as he must have known it would. But he ached to see those mountains from the air. He returned to Germany and wrote another successful book, Voyage to Wonderland. Proceeds from this literary effort earned Pluschow enough cash to finance a private expedition to South America.

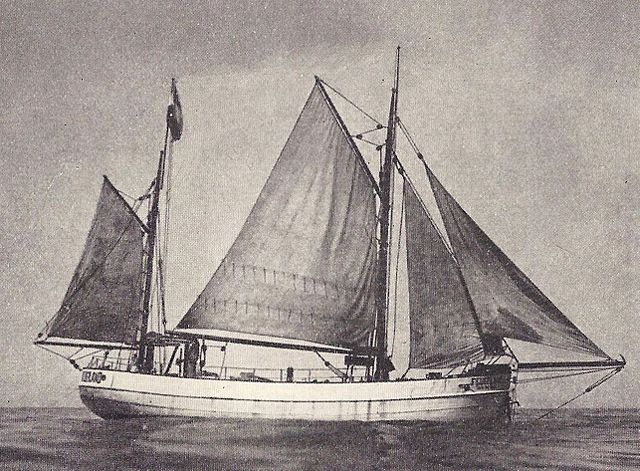

In 1928, the former military man finally emerged as the explorer he’d long wanted to be. Teaming up with an engineer, Ernst Dreblow, Pluschow bought a ship and a Heinkel HD 24 D-1313 seaplane. Their inaugural flight was a trip from Punta Arenas, Chili, to Ushuaia, Argentina — delivering Ushuaia’s first air mail along the way.

Pluschow’s ship, the ‘Feuerland.’ He eventually had to sell it in order to raise enough money to return home from his first South American expedition. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

A whirlwind of discovery

The flights that followed were a whirlwind of exploration and discovery. It was such a productive time that it makes one wonder what Pluschow could have accomplished had he lived past 1931. Pluschow, Dreblow, and their dog Schnauf were the first to explore some of the region’s most famous geological features by air. They flew over the ice-choked Cordillera Darwin, surveyed Cape Horn, looked down at the beautiful Southern Patagonian Ice Field, and soared past the towering Torres del Paine. Their work was critical in the mapmaking efforts ongoing in the rugged area.

The Heinkel HD 24 D-1313 Pluschow used on his South American expeditions. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Pluschow had so much fun exploring Patagonia that he took his funding right down to the wire, eventually having to sell his ship to scrape together enough money to return to Germany in 1929.

A budding filmmaker, Pluschow spent part of his time in South America shooting roll after roll of motion picture film, eventually cutting a documentary. The film, called Silver Condor over Tierra del Fuego, was released concurrently with a book of the same name.

Return to Patagonia

The film and book once again earned Pluschow enough cash to return to South America in 1930. But here, the pilot’s phenomenal luck ran out. He and Dreblow were both killed in a plane crash in early 1931 on Lake Argentino.

It feels supremely unfair that a man who worked so hard to become an explorer was killed doing that very thing. Pluschow didn’t come from money, and large exploration societies didn’t finance his expeditions. He funded his travels through creativity and storytelling, often waiting agonizing months or years between adventures while the funds accumulated.

The grit, perseverance, creativity, and courage he showed in the early parts of his life were also on display during his time in South America. There is no doubt that had he lived longer, he would have become a towering figure in South American exploration rather than the footnote he is today.

He was a lucky man but also phenomenally unlucky. Were it not for the Great War, he would surely have found a way to Patagonia much earlier in his life.