Today is the 58th anniversary of the first ascent of 4,892m Mount Vinson, the highest peak in Antarctica.

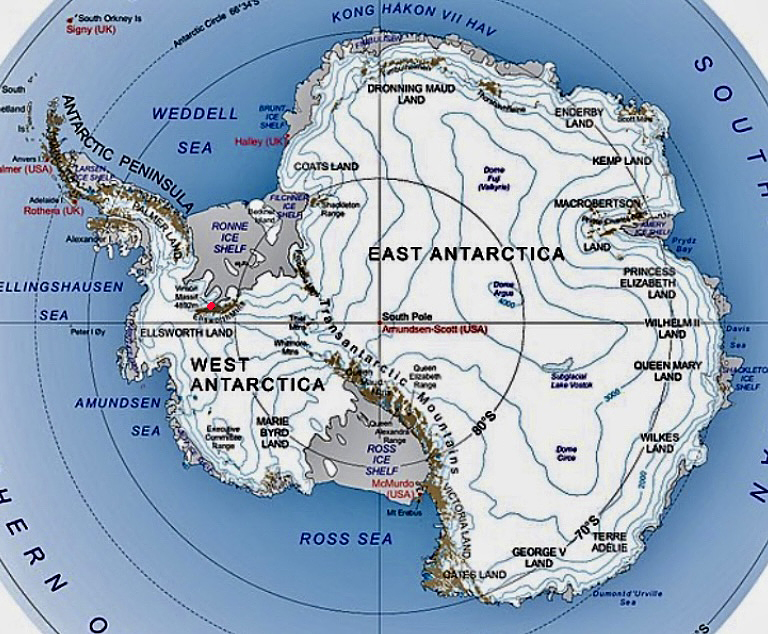

Antarctica has three main mountain ranges. The Antarctic Peninsula Cordillera runs the full length of the Antarctic Peninsula. Further south lie the Ellsworth Mountains. Finally, the Transantarctic Mountains run north to south, splitting the continent into East and West Antarctica. Mount Vinson is in the Sentinel Range of the Ellsworth Mountains.

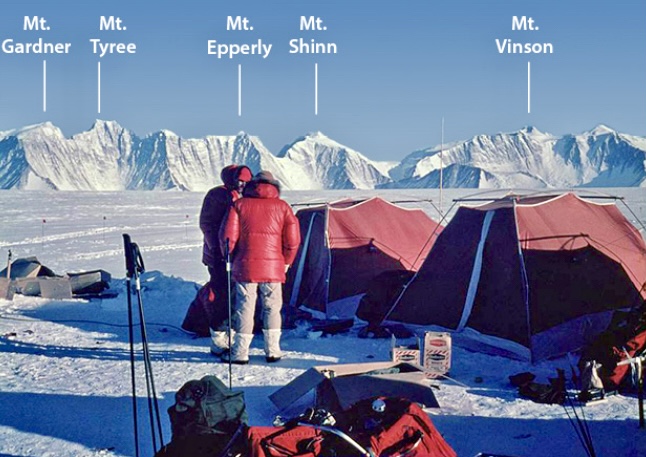

The Ellsworth Mountains run 360km from north to south beside the Ronne Ice Shelf and are 48km wide. The northern half of the Ellsworth Mountains is called the Sentinel Range. It features 33 peaks. The next highest peak after Vinson is 4,852m Mount Tyree.

Antarctica and its mountains. The red dot marks the location of Mount Vinson. Photo: MountainIQ

The Vinson Massif

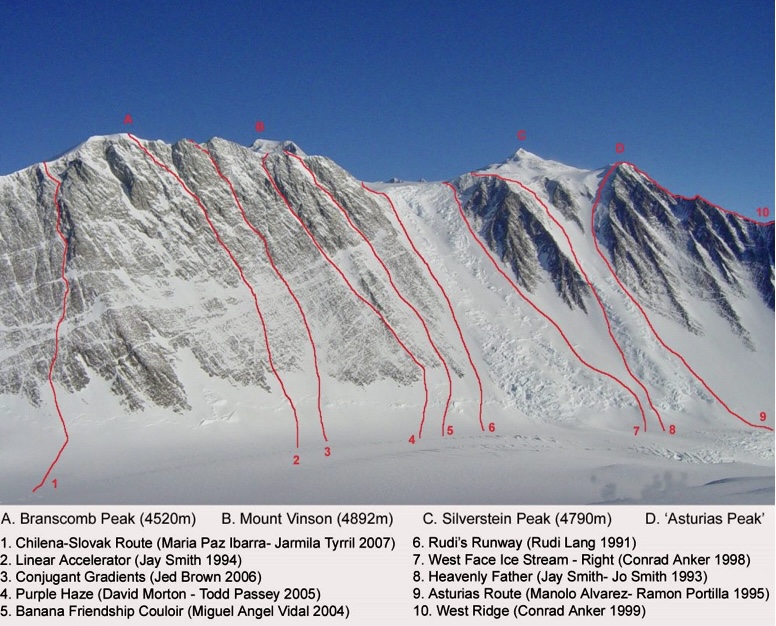

In his book Mountaineering in Antarctica: Climbing in the Frozen South, Damien Gildea described the Vinson Massif as “a great white bulk of terrain around 15km long by 15km wide…crowned with numerous small peaks situated around a high, windswept plateau of bare ice, from which several long ridges drop down to the surrounding glaciers.”

Mount Vinson was named after U.S. Senator Carl G. Vinson for his support of U.S. activity in Antarctica during the mid-20th century. In fact, researchers had already proposed the name “Vinson” for Antarctica’s highest mountain even before explorers found it.

Until 2006, Antarctica’s highest mountain was called Vinson Massif rather than Mount Vinson. In 2006, after several climbing and GPS mapping expeditions in the Sentinel Range, researchers suggested that Mount Vinson should specifically denote the highest summit of this massif. The Antarctic Place Names Committee of the U.S. Geological Survey accepted the proposal.

Some of the big mountains in the Sentinel Range. Photo: John Evans

The discovery of the Vinson Massif

On Nov. 23, 1935, American aviator Lincoln Ellsworth flew over the Sentinel Range. But thick clouds meant he could only spot only one small peak. He named it Mount Ulmer after his wife, Marie Louise Ulmer.

Antarctica’s highest mountains remained almost completely unknown until the 1950s. In 1957, a U.S. Navy flight spotted the peaks of the Vinson Massif.

In January 1958, a U.S. Navy flight from Byrd Station sighted high mountains further east in Ellsworth Land. During the 1958-59 season, a ground party headed in this direction and found mountains that seemed higher than anything yet discovered on the coldest continent. This was the Vinson Massif.

In 1961, U.S. scientists Tom Bastien and John Splettstoesser climbed 2,370m Mount Wyatt Earp at the northern end of the Sentinel Range. Researchers explored Union Glacier and nearby areas in 1963 and 1964 but did not make any significant ascents.

A Twin Otter at Vinson Base Camp. Photo: Damien Gildea

A coveted target

In 1960-61, The Mountain World published a picture of the Vinson Massif and proclaimed it the highest peak in Antarctica.

“Independently, and very nearly simultaneously, this generated interest among the [climbing] groups in the United States,” Brian Marts wrote in the American Alpine Journal.

It was a tempting target. Mount Vinson remained unclimbed, and the whole range was untouched except for geologists’ ventures onto lower peaks.

One climbing group approached the problem of obtaining permission and support with a scientifically oriented expedition proposal, while another appealed strictly from a mountaineering standpoint.

In September 1966, Nicholas Clinch, the only American to lead a first ascent of an 8,000’er (Gasherbrum I in 1958), received a phone call. The U.S. government would grant the American Alpine Club permission for an expedition to Antarctica, and Clinch would lead it.

The two climbing groups hoping to make the first ascent of the Vinson Massif were merged to form the American Antarctic Mountaineering Expedition. The team included J. Barry Corbet, Eiichi Fukushima, Brian Marts, Pete Schoening, Samuel Silverstein, Richard Wahlstrom, William Long, John Evans, and Charles Hollister.

Looking south over the Vinson Massif from the upper southwest face of Mt. Shinn. Photo: Damien Gildea

Arrival

On Dec. 3, 1966, the team arrived in New Zealand then boarded a Navy C-130 transport plane.

Arriving in Antarctica, they spent about 30 hours repacking and organizing at McMurdo Base and then flew to the range. Because of poor visibility, they could not land. Instead, they diverted to Byrd Station, where they waited for 10 hours.

“From the air, the peaks had been spectacular,” Marts said in his expedition report. “Here on the plain, they were overwhelming. Rising abruptly from the flat plateau, this was the most beautiful range I had ever seen.”

On December 8, the team landed a ski-equipped LC-130 on flat ice around 20km west of the main peaks. From there, they used a snowmobile to carry their supplies closer to the mountain.

The 1966 team at McMurdo. Photo: John Evans

The first ascent

On December 9, they set up Base Camp and fixed rope to a col at 3,353m. There, the reconnaissance party of Sam Silverstein, Dick Wahlstrom, and Eiichi Fukushima established a camp.

They identified a narrow gap in the ridge running southwest from Mount Shinn as a possible entry point to the actual slopes of Vinson and named it Sam’s Col.

The team found a route through the icefall to the Vinson-Shinn saddle at 4,206m and returned to Base Camp. Thus far, the weather had been perfect, but on the evening of December 15, a storm arrived.

“Within three hours, the base was a shambles. Two of our tents were flattened, and gear was strewn about the glacier,” Marts recalled.

The storm continued until December 17. Afterward, the team couldn’t find all their gear, but the expedition continued.

Schoening and Evans on the summit of Mount Vinson on Dec. 18, 1966. Photo: John Evans

On December 17, Pete Schoening, John Evans, Barry Corbet, and Bill Long moved past Camp 2 and set up Camp 3 at 4,510m. Meanwhile, three more team members moved to Camp 1.

On December 18, Barry Corbet, John Evans, Bill Long, and Pete Schoening reached the summit of Mount Vinson. They took photos with the flags of the 12 original signatories of the Antarctic Treaty arranged in a circle. Over the next two days, the rest of the team also summited.

Low Camp, High Camp, and the summit of Vinson. Photo: Damien Gildea

Other ascents by the 1966 team

On December 21, 22, and 24, team members ascended Mount Shinn. On Jan. 6, 1967, Corbet and Evans ascended Mount Tyree. On January 12, Long, Schoening, Fukushima, and Marts ascended Long Gables. The same day, Evans, Wahlstrom Hollister, and Silverstein ascended Ostenso.

Unauthorized ascent

The second ascent of Mount Vinson came on Dec. 22, 1979. Werner Buggisch and Peter von Gizycki from Germany, and Victor Samsonov from Russia followed the American route. But their expedition was not authorized.

According to Damien Gildea, the three men needed to do field work low on the mountain but were instructed not to go for the summit.

“Yet, after being dropped by helicopter at a base west of Sam’s Col, they could not resist the urge to climb Antarctica’s highest peak,” Gildea wrote in his book.

They left Samsonov’s ski pole with a red flag on the top.

In 1983, Dick Bass and Frank Wells were pursuing the then-novel idea of the Seven Summits. On their expedition to Vinson, they were joined by Chris Bonington, Rick Ridgeway, and Steven Marts (who filmed the climb). Bonington reached the summit with Bass, while Wells and the others topped out a week later.

Mountaineers move up to High Camp on Mount Vinson. Photo: Madison Mountaineering

The Vinson flag mystery

John Evans, part of the first ascent team, recounted a funny story in his book about the first ascent of Vinson. The later 1979 team found a flag flying from a bamboo pole on the summit. Evans did not believe that a flag could have survived on the top for so long in Antarctica’s harsh wind. But who else could have put the flag there?

Evans believed that somebody may have snuck to the top. So he started doing some detective work.

Evans got in touch with Gizycki from the 1979 team. Gizycki told Evans that he had brought the flag back to Germany and had it in his basement. He sent Evans some pictures of the flag.

“Armed with these pictures, I proceeded to pester a great number of busy people in the hope of at least ascertaining the country of origin,” Evans wrote in his book.

Evans also returned to his summit photos from Dec. 18, 1966. There, to his embarrassment, he found the answer.

In one of the photos, Bill Long was posing on Mount Vinson’s summit with that mysterious flag.

“Bill confirmed forthwith that it was the flag of his home institution, Alaska Methodist University, and that he had planted it on the summit in my presence before we started down,” Evans wrote.

How the flag survived 13 years on the summit remains a mystery.

Peter von Gizycki presents Bill Long’s 1966 summit flag to Pete Schoening’s daughter in Germany in 2007. Photo: John Evans

Some more notes

Since its first ascent, approximately 1,400 people have ascended Mount Vinson, with no deaths registered. It costs around $54,000 per person to climb Vinson.

In 2004, Rodrigo Fica, Damien Gildea, and Camilo Rada measured the height of Vinson using GPS. This team also made first ascents of many sub-peaks on the Vinson summit plateau.

On Jan. 1, 2005, Gildea removed the summit register book on Vinson from the aluminum cylinder in which it had sat for decades.

“The book was full, no longer useable, and I felt it would be too tempting a prize for a thief, given some recent similar problems in Antarctica,” Gildea wrote in the American Alpine Journal. The book is in the American Alpine Club museum. A replacement register was organized.

Some non-standard routes up the Vinson Massif. Photo: Damien Gildea

For more on Mount Vinson and the 1966-67 expedition, we recommend: Vinson and Tyree, Antarctica: The 1966-67 American Antarctic Mountaineering Expedition by John Evans and Mountaineering in Antarctica: Climbing in the Frozen South by Damien Gildea.

You can read a climber’s guide to Mount Vinson here.