In the early hours of January 3, 1864, the anchor chain that tethered the 56-ton schooner Grafton to the sea bed off southern New Zealand snapped loose. Ninety minutes later, the gale that had been pounding the ship for almost two days drove the Grafton onto the rocks off Auckland Island.

At first, it appeared that the Grafton, a rugged ship outfitted for the Southern Hemisphere’s treacherous waters, might survive. But with a disheartening crunch, the combination of water, waves, and rocks ripped her keel, and seawater poured in. The Grafton was finished.

But the five men aboard, including Captain Thomas Musgrave and voyage sponsor Francois Raynal, weren’t finished. They gathered beneath a sail and waited for a stormy dawn to break. When it did, they loaded up the ship’s dinghy with whatever supplies they could gather: a double-barreled rifle, ammunition, navigational instruments, cooking gear, ship’s biscuits, flour, tea, coffee, pork, and tobacco.

The remains of the ‘Grafton’ in a photo from 1909. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

But the shore lay across a swirling channel still beset by the gale. Thinking quickly, Norwegian Alexander Maclaren dove into the water, swam the waves, and rigged up a pulley system on a tree near the shore. The men got the canoe across in this way, then returned again to harvest planks, rope, and other building materials from the stricken Grafton. As the rain continued to hammer down, they built a rude hut and piled in to snatch what sleep they could.

The shelter would be their home for the next 18 months.

A failed venture, a strange crew

The Grafton Castaways, as history would come to call them, were a mixed bag.

Musgrave was an Englishman who, at 31, had been at sea for over half his life. When the Grafton foundered, he’d been living in Australia with his family for five years.

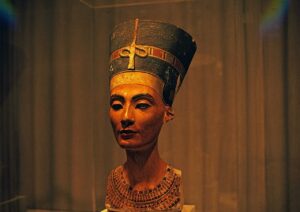

Thomas Musgrave. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Raynal was a French adventurer who’d given up life on the ocean for 11 years in the Australian goldfields. There, he survived a mine collapse and a lingering infection — one that had left him bedridden for a month at the time of the wreck. The Grafton’s voyage was his idea, an expedition to seek out tin on Campbell Island. Musgrave was the nephew of one of Raynal’s business partners.

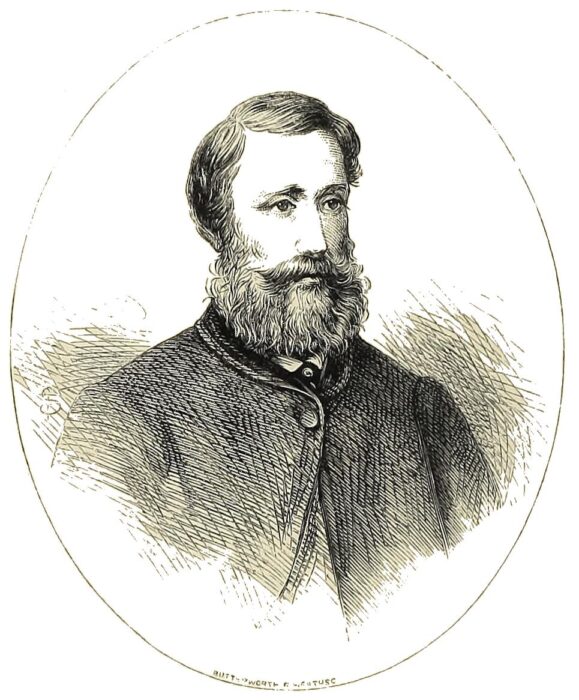

Francois Raynal. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Maclaren was a lifelong sailor, experienced and reserved. The young man of the crew was George Harris, just 20. And rounding out the bunch was Henry Forges, ship’s cook, sporting a leprosy-riddled face and a javelin injury from his time as the captive of Indigenous people on Samoa.

After failing to find the rumored tin on Campbell Island, Raynal attempted to turn a profit on the voyage by harvesting skins and oil. Auckland Island, devoid of human life but with a prodigious seal and sea lion population, seemed like a safe bet.

But before they could put ashore, the storm struck.

‘The black, coarse, oleaginous flesh’

On the first morning of the ordeal, the men killed and ate a young sea lion. It was a disagreeable meal.

“The black, coarse, oleaginous flesh, which was as little agreeable to the smell as to the taste, did not appear to us a very satisfactory repast,” Raynal recorded. “But we felt we must accustom ourselves to it.”

He was right. Over the next 18 months, sea lions would be the staple food for the castaways. Understandably, they came to hate it. Yet they knew enough about sea lion behavior to understand that eventually, the animals would move on from the island. The castaways ate while they could.

The weather was uniformly dreary and cold, and boredom — and the ill-tempers that came with it — was more of a threat than starvation in the early days.

Sea lions made up the bulk of both castaway group’s diets. Photo: Shutterstock

But Raynal and Musgrave had no intention of letting their crew succumb to melancholy. From the very beginning, they enacted several policies that have become a model for leadership and group management in survival situations.

For starters, the two leaders immediately shared supplies that had originally been slated for their use alone onboard the ship. They kept the men busy with continuous improvements to their hut, which was swiftly dubbed Epigwaitt. Soon enough, the dwelling had a cot for each man, homemade lamps, a fireplace, a chimney, a desk, and other amenities. They established a school and had regular lessons with Musgrave and Raynel, who were particularly insistent on teaching the illiterate Maclaren how to read.

The crew even managed to brew some beer using Stilbocarpa, a type of ground-hugging flowering plant, which lifted spirits considerably. Raynel also made a chessboard, dice, and cards.

‘We stood so much in need of one another’

But perhaps most importantly, the castaways established clear tasks for each man and a system of governance, holding elections for leadership (which Musgrave, naturally, won). The little makeshift government came complete with rules scribbled in the margins of Musgrave’s Bible, which he read aloud every Sunday.

“Assuredly, we had lived together since our shipwreck in peace and harmony — I may even say in true and honest brotherhood,” Raynal later wrote in an account of the wreck.

He admitted that occasional disagreements led to momentary anger and cross words, but they never let the bad feelings fester.

“If habits of bitterness and animosity were established amongst us, the consequences [would be] disastrous,” he said. “We stood so much in need of one another!”

As May and winter in the Southern Hemisphere approached, animal life on the island became scarce. The Grafton castaways steeled themselves for lean days. They knew that rescue wasn’t coming until spring, at the very earliest.

Another group of castaways

Meanwhile, elsewhere on the island, another bunch of castaways was also struggling to survive — and neither group was aware of the other.

On May 11, 1864, an autumn storm blew the Invercauld against the rocks on Auckland Island’s northern tip, about 40km from the first group. Nineteen of the ship’s 25-man crew made it ashore, including the leadership: Captain George Dalgarno, first mate Andrew Smith, and second mate James Mahoney.

But Dalgarno’s leadership style in the face of disaster was markedly different from that of Musgrave and Raynel’s. And the fate of his unhappy crew was tied to his missteps.

To start with, Dalgarno did not maintain a steady head during the wreck itself. He gave no order to abandon ship, and the men simply swam for shore as they saw fit. As a result, the crew that survived had far fewer supplies and tools than did those from the Grafton.

Dalgarno also proved ineffective in the first days of the wreck. He allowed his men to huddle in a poorly constructed and far-too-cramped shelter on the beach. He issued no orders to improve the shelter, instead commanding the lower-ranking men to serve the higher ranks as if they were all still aboard the ship. The crew burned precious calories fetching food and water for the Captain and mates.

Bored, starving, and chafing under a command structure ill-suited to the circumstances, the men talked of cannibalism before the month was out. And by the end of May, their numbers had been reduced to 10 by exposure and lack of nutrition. Eventually, one of the lower-ranking men, 23-year-old Robert Holding, convinced some of the others to go foraging with him. They found a row of berry bushes and followed it to the abandoned settlement of Hardwicke.

When the crew of the ‘Invercauld’ reached Hardwicke, they found an abandoned town, complete with a graveyard. But few buildings remained standing. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Only one of the ghost town’s 18 buildings was habitable, but it was better than a lean-to on a beach. And the village turned up a few usable tools. But far from being their salvation, finding the village would have dire physiological consequences for the Invercauld crew.

Rather than being proactive and improving Hardwicke’s structures for long-term use, the men — with the notable exception of Holding — believed the abandoned village was proof they’d soon be rescued. They continued to live on a meager diet of limpets, seals, and foraged plants while they waited out the long winter, mostly exposed to the elements. Always, they expected to see a ship on the horizon.

Physical conflict, starvation, and overwork in the service of the crew’s leadership claimed more lives. Captain Dalgarno even abandoned his injured first mate Mahoney in a shack, leaving him to starve in isolation.

Eventually, the men were eating corpses.

A despondent Christmas

Meanwhile the crew of the Grafton had come to realize if they wanted to survive, they’d have to help themselves.

But it was a near thing. Spring arrived, and with it, more abundant hunting but no rescue ships. Despondency began to set in.

“My companions were lying on the ground, silent, their countenances dark with the dreariest melancholy,” Raynal wrote. “Evidently, they had been the victims of regrets as bitter and despair as great as mine.”

Even Musgrave gave in to hopelessness.

The remains of the hut built by the Grafton castaways. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

“Well,” he said, “what matters it, since we are destined to die here? Better to bring our misery to an end at once. What is the use of living? Of what profit is life in such circumstances as ours?”

On Christmas Day, surveying the listless crew, Raynal felt the hopelessness encroaching within him finally give way to something more potent.

“I felt a complete revolution working within me. To depression succeeded a kind of exaltation; my heart, reinspired by a transport of pride, indignation, and almost wrath, beat violently,” he remembered. “If men abandon us, let us save ourselves,” he said to the men. “Courage, then, and to work!”

Boats and forges

The Grafton castaways proposed to build a boat.

But to do so, they’d need nails and tools, and for that, they needed a forge.

They made one from scratch by January 16 and started churning out 50 nails a day. But they soon realized building a totally new boat would take at least a year and a half at the pace they were working. They changed tacks and began to modify the Grafton’s canoe for an open-water voyage—knowing its small size would mean leaving two men behind while three went for help.

The group’s division of labor continued smoothly as well, with some of the men in charge of foraging and upkeep on the hut and others taking shifts on the boat construction.

Decking appeared, and planks caulked with gum of lime and seal oil. Parts scavaged from the Grafton provided a mast, a pump, and a compass. By June 1865, and entering into the castaway’s second winter, it was ready.

“Our work being completed, it presented to the gaze — at all events, to that of its authors — a very imposing appearance,” wrote Raynal. “It was a decked boat, 17 feet long, six feet wide, and three feet deep.”

They named her Rescue.

Last men standing

On the north end of the island, only three men remained. The resourceful and tireless Holding, Captain Dalgarno, and first mate Andrew Smith. Holding had finally taken command of his useless officers, and under his leadership, the trio was clinging — tenuously — to life.

On May 22, 1865, they finally got the lucky break that 16 men had died waiting for. The Portuguese brig Julian sailed into view, seeking a resupply. Despite the presence of plague on board, the Invercauld’s crew scrambled aboard. There, Dalgarno and Smith were taken to officers’ quarters, while Holding was relegated to the lower decks. The officers ordered Holding not to reveal he’d been the key to their survival.

After Julian made port in South America, they left him behind to make his own way home. He survived on charity until he secured a post on a ship bound for the Netherlands.

Rescue

On July 12, 1865, the five Grafton castaways launched Rescue. Raynal, Musgrave, and Maclaren — the crew’s three most experienced sailors — were aboard. It was an emotional moment for all five men.

“We were on the point of separating from two of our companions — from George and Henry — who for 19 months had shared, day after day, our struggles and our sufferings, with whom we had lived as brothers,” Raynal remembered.

If all went well, the men of the Rescue hoped to reach New Zealand in 60 hours. But a storm battered them for four days. Eventually, they spotted the settled island of Rakiura, but the wind blew them back out to sea, and they didn’t have the strength to fight against it with oars.

“We saw ourselves on the point of drifting out to sea and perishing in sight of port,” Raynal wrote of the dark moment.

But on July 24, 1865, 12 days after leaving the Auckland Islands in their jerry-rigged craft, Raynal, Musgrave, and Maclaren made port on Rakiura. Raynal collapsed into another relapse of his illness, but Musgrave found the strength to convince the cutter Flying Scud to mount a rescue.

It doesn’t take much imagination to realize what Dalgarno would have done at this point. He’d have stayed on Rakiura.

But Musgrave, as he demonstrated time and time again during the ordeal, was made of better stuff. He accompanied Flying Scud back to Auckland Island, knowing that the treacherous winter seas had every chance of stranding him there again. There, he found his two remaining crew alive and well, despite a brief falling out that had sent them to opposite ends of the island in a fit of pique.

But in final evidence of the spirit that allowed the Grafton castaways to survive an experience that claimed so many other lives, the two made up as soon as they were rescued.