Fictional mystery stories are nice and tidy — all the puzzle pieces slotting nicely into place, every thread untangled, every question answered. But real-life mysteries are rarely like that. Especially historical mysteries. Time has a way of obscuring events that were confusing to begin with.

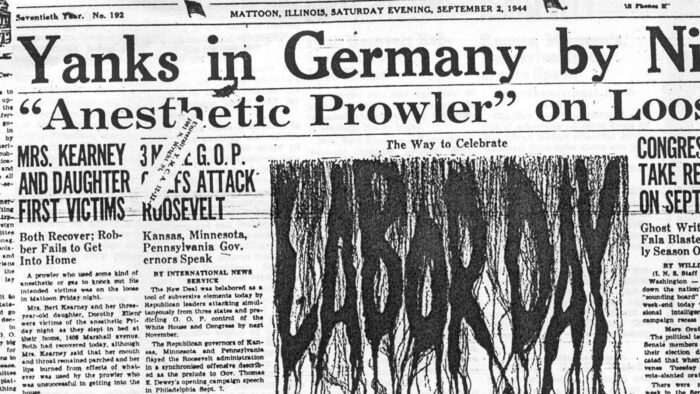

Such is the case with the “Mad Gasser of Mattoon,” also known quite spectacularly as the “Anesthetic Prowler” and the “Phantom Anesthetist.” Over a period of several weeks in 1944, in a small town in Illinois, dozens of people reported a sickly sweet smell followed by lower-body paralysis, coughing, nausea, and vomiting. More worrisome, several affected people reported seeing a figure described variously as “tall and dressed in black,” “ape-like,” or even “a woman dressed as a man.” The symptoms almost always cleared up within the hour, and no one was seriously injured or even hospitalized.

Curiously, the whole thing stopped by itself in less than a month.

The mystery is a fascinating one to study, because even though it occurred over 80 years ago, the lessons it teaches — about communities under stress and the creeping power of fear — are timeless.

A shape in the dark

August 31, 1944. A man named Urban Raef woke up to a strange smell and a fit of vomiting. His wife, concerned that their gas stove was to blame, tried to get up to check it. But she was paralyzed from the waist down, unable to leave the bed.

Later that night or the next morning (accounts vary), a young mother living nearby had a similar experience. She woke to the sound of her child coughing but was unable to leave the bed to investigate.

The next night, on September 1, things escalated.

Mattoon, Illinois, site of the Mad Gasser’s attacks — or was it? Photo: Shutterstock

At 11 pm, Aline Kearney noticed a powerful, sickly sweet smell. Quickly after that, she began to cough and lose feeling in her legs. Her daughter, sharing a bedroom with her, had the same symptoms. Kearney’s sister, Mrs. Ready, also noticed the smell and identified it as coming from a nearby open window.

At 12:30 am, Aline’s husband, Bert Kearney, arrived home from his taxi-driving job and noticed a shadowy figure lurking near another of the house’s windows. Kearney tried to chase the darkly clothed man but came up empty. The family called the police, but there was no evidence the man was ever there.

All of the people affected by the strange symptoms during those two evenings recovered within hours, to no lasting effect.

Power of the press

Authorities at the time, as well as later historians and psychologists, believe these accounts are mostly true. Something was probably going on, and it could have been a number of things. But what came next, well, that’s harder to untangle.

An excitable press got wind of the stories, and the Mad Gasser of Mattoon was born.

After story hit the papers, an avalanche of reports came in. And wouldn’t you know it, most of them described similar symptoms and the same dark, ominous figure.

Other details cropped up. Here, a cloth smelling of a mysterious chemical. There, a “well-used” skeleton key. Footprints under windows. Slits in window screens. Mrs. Leonard Burrel claimed she was lying in her bed when a dark shape broke through and tried to gas her. Some people claimed they’d been attacked months before. A local fortune teller excitedly told anyone who would listen that an “ape-like man with long arms, reaching out, holding a spray gun” had blown arm-numbing clouds of gas in her direction.

We hope whoever came up with “Anesthetic Prowler” got a raise. Photo: Public domain

A panicked public

Panic spread. Armed vigilantes patrolled at night, and a woman blew a hole in her wall trying to load her husband’s shotgun. The army brought in a chemical weapons expert to investigate. The FBI got involved. Local authorities threw half a dozen theories at the wall, looking for anything that stuck.

A disgruntled high-school chemistry teacher? German or Japanese saboteurs? A sociopath? An escaped mental patient?

But as the weeks went on, the police and FBI never turned up any physical evidence of the shadowy figure. The Army’s chemical weapons expert never found anything suspicious at the scenes. Mattoon Police Chief Eugene C. Cole’s eventual theory was of lingering chemicals from a nearby factory producing shell casings for the war effort. But after one of the “victims” turned out to have been smelling a spilled bottle of nail polish, he developed a new idea: good old-fashioned mass hysteria (now called mass psychological disturbances).

When the press reported this new theory — and Mattoon’s public health officials got on board with the idea — the reports petered out.

The powder keg

The timeline of attacks has Urban Raef, his wife, and the nearby mother as the first victims. But it’s important to note that the Kearney family was the first to report both the “gas attack” and the “shadowy figure” to the police, and their account was the first to appear in papers.

Complicating this all is that one of the newspapers ran a headline that screamed: “Mrs. Kearney and Daughter First Victims” (emphasis ExplorersWeb). So it’s entirely possible that later accounts came from an assumption that other attacks were soon on the way. As more attacks were reported, more people came forward with attacks. A pernicious self-feeding frenzy began.

And what about the Kearney family? It seems likely that Aline Kearney did experience some kind of temporary medical problem, but what it was is unknown. Did Bert Kearney see a figure lurking under his window? Maybe, but eyewitness statements are notably untrustworthy.

Mattoon’s now-shuttered movie theater would have been hopping in 1944, except in September, when Mad Gasser panic swept the streets. Photo: Shutterstock

Wartime paranoia

And you have to remember what kind of atmosphere existed in 1944. The country was at war, towns were empty of young and middle-aged men, and the fear of sabotage or domestic attacks was ever-present. Most Americans expected to see enemies around any corner at any time. It was, in essence, a powder keg — into which one woman’s fleeting and mysterious illness threw a match.

That’s the tack that most research into Mattoon’s Mad Gasser has taken in the years since. The incident has become a case study for how news cycles and the public interact (and if that isn’t a relevant lesson for today’s world, nothing is.) Every few decades, another researcher publishes a paper that comes to the same conclusion. Some kind of inciting incident — be it a one-off attack, a short-lived chemical spill, an isolated medical issue, or a war-and-stress-related flight of imagination — caused a self-perpetuating panic.

But of course, we’ll never really know for sure, will we? That’s what makes it a good mystery.

History drones on

If this sounds familiar, consider the recent and mysterious New Jersey drones. What began as a single sighting of unidentified drones in mid-November has become a six-state, daily phenomenon. Political figures all the way up to the President-elect have weighed in, the Army is involved, and multiple “sightings” have turned out to be airplanes, planets, or other easily explainable things. Easiest explanation? Lots of people have drones and fly them where they shouldn’t — especially since reporting on the sightings has become so ubiquitous that drone owners are curious about what’s up there.

We’ve come a long way from our grandparents in terms of technology, and in many ways, the world we live in is radically different than it was 80 years ago.

But if there’s an enduring lesson to history, it’s this — people are people.