Robert Eggers’ film Nosferatu has renewed interest in vampires. Folklore about them abounds, and their presence — or preventing their presence — used to be a real concern. Some archaeologists refer to mysterious graves around Europe and North America as “anti-vampire” burials. These feature iron stakes through hearts, decapitations, sickles placed on necks, and bricks in mouths.

A common practice

Many graves show human remains that people have desecrated, rearranged, and interred with “preventive measures” to ensure the dead didn’t return as vampires.

Sometimes, people buried the deceased on their side or with the skull face down. They stuffed stones or bricks in the skull’s jaw to prevent the corpse from chewing through wrappings. Other times, they chained or nailed the body down or even decapitated the corpse.

Vampire grave in Zamkowa Street, Poland. Photo: R. Biskupski/Kotowicz

The Mercy Brown case

Vampires didn’t just occur in Transylvania. In 1892, in Exeter, Rhode Island, several members of the Brown family were suffering from tuberculosis. As they wasted away, they looked like living corpses, with sunken eyes and extremely pale skin. Mary Brown and one of her daughters, Mary Olive, died of the affliction. This left George Brown, his son Edwin, and his daughter Mercy Lena.

Then Edwin fell ill. After taking advice from local doctors, he escaped to another state with better weather. There, his health improved a little.

Mercy was also ill, but her case was unusual. She was almost asymptomatic, and minor symptoms that did arise came and went for years. Yet she died at 19 in 1892.

The deaths prompted rumor and speculation.

A local newspaper article from 1892 stated:

During the few weeks past, Mr. Brown has been besieged on all sides by several people who expressed implicit faith in the old theory that — by some unexplained and unreasonable way — in some part of the deceased relative’s body, live flesh and blood might be found, which is supposed to feed upon the living who are in feeble health.

People believed the deaths were supernatural, and the panicked townsfolk pleaded with George Brown to exhume the bodies of his family. A neighbor suggested that Mercy might have caused Edwin’s condition and the deaths of her family. He thought Mercy’s corpse could rise from the grave as a vampire.

In response to this local paranoia, the Brown family consulted a local doctor. The doctor believed that exhuming the bodies might provide some answers.

Mercy’s body, unlike those of her mother and sister, appeared remarkably well-preserved. Despite nearly two months in the ground, she had a ruddy, reddish complexion, and her mouth was slightly open. Locals took this as a sign that she was feeding on the blood of the living.

They removed her heart and liver, reportedly still in a “bloody” state. This was considered another telltale sign she was responsible for the deaths in her family. They cremated her heart and liver, mixed her ashes into tea, and fed it to her sickly brother Edwin. Whatever they hoped this would accomplish, it didn’t work. He died some months later.

New England’s Vampire Panic

A similar story occurred decades earlier. The Ray family from Jewett City, Connecticut, also suffered from a disease now suspected to be tuberculosis. The father and his two sons died, and another son fell ill soon after.

The bodies of the deceased sons were exhumed and burned. They became widely known as the Jewett City Vampires.

Jewett City became a hotspot for grave desecration. Smithsonian Magazine writer Abigail Tucker recounts another eerie discovery from the 1990s.

A group of children found human remains near a mine. Experts dated the bones to the 1840s, and subsequent archaeological excavations found 29 more skeletons. One stood out.

J.B. (as shown on his tombstone) was decapitated, and his ribs shattered. His coffin was also smashed. Either someone hated him, or he was a “vampire.”

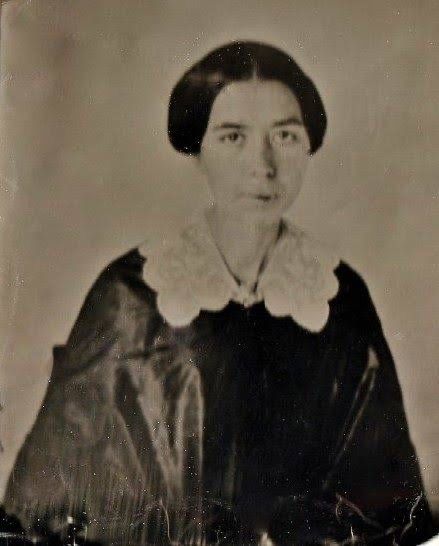

Mercy Brown. Photo: Unknown

The discovery led to hysteria and paranoia. Historians called this madness the New England Vampire Panic. Just as witch hysteria in the 1600s made people fear the living, so this prompted widespread fear of the dead.

Michael E. Bell, a prominent figure in the New England folklore community, spent his life collecting stories of the region’s vampires. His blog, Vampires Grasp, delves into oral and family histories. His most famous work, Food of the Dead, contains interviews with the descendants of these so-called vampires. He spoke with Mercy Brown’s descendant, Everett, who told him that the vampire panic did not stop with Mercy’s death and exhumation:

Everett was angry and sad as he described some of the negative attention that Mercy’s grave attracts. People were taking chips from the stone as mementos, and some were even placing tape recorders in her grave.

In 1996, someone stole her gravestone. Our morbid fascination with the unexplained remains unchanged.

Were vampires simply outcasts?

Europe also experienced vampire panic.

On the Greek island of Lesbos, archaeologist Hector Williams uncovered a male skeleton whose corpse was nailed down by iron spikes. The spikes went through his ankles, pelvis, and neck.

We’re used to tales of Count Dracula and Vlad the Impaler from the wilds of Romania, but Poland is perhaps where the vampire myth is strongest. Apotropaic Practices and the Undead: A Biogeochemical Assessment of Deviant Burials in Post-Medieval Poland by a research team led by Lesley A. Gregoricka investigated anti-vampire or “deviant” burials in Poland. They looked for links to immigrant communities or other marginalized groups.

The study examined local cultural practices during the medieval period:

Individuals ostracized during life for their strange physical features, those born out of wedlock or who remained unbaptized, and anyone whose death was unusual in some way — untimely, violent, the result of suicide, or even as the first to die in an infectious disease outbreak — all were considered vulnerable to reanimation after death.

[…] Of these six individuals, five were interred with a sickle placed across the throat or abdomen, intended to remove the head or open the gut should they attempt to rise from the grave.

Two individuals also had large stones positioned beneath their chins, likely as a preventative measure to keep the individual from biting others or to block the throat so that the individual was unable to feed on the living.

The study also provides evidence that these individuals were from other parts of Europe. Could this suggest a link between vampires and migrants? Perhaps deeming someone a vampire was a form of prejudice.

A vampire grave in Venice. Photo: Matteo Borrini

A scapegoat for the unexplained

Vampire stories feature common themes, such as fear of disease. At the time, people did not understand germs and bacteria, and tuberculosis and infection could easily acquire supernatural portents. People also believed diseases were God’s punishment, not a natural part of life. Unexplained deaths easily led to supernatural rumors and, occasionally, to vampire panics.