I’m halfway up the wall, and I’m in trouble. Excited by the prospect of my first climb outside the confines of the gym where I trained, I neglected to plan my route all the way to the apex of my climb. Instead, on the ground, I chose a likely outcropping and sent it, only to realize 20 meters later that my line terminated in a smooth granite face.

My toes are balanced on a narrow crack just wide enough to support my weight, and my body is pressed against the stone. My arms are outstretched, smearing my torso on the rock face and relying on friction and prayer to keep me upright. I look to my left. There’s a tiny knob, maybe a meter away. If I lean and commit, I might catch the knob before gravity catches me. But there’s no going back if I do. A butterfly floats by my face. I don’t know what to do.

In the video game I’m playing, my character Aava’s arms and legs start to tremble, and her breathing quickens. It’s the game’s way of telling me I’d better master this decision paralysis quickly before I lose my grip and drop to the ground.

In real life, sitting at my desk and staring at my computer screen, my palms start to sweat.

And that’s kind of remarkable.

Who are climbing games for?

Climbing games are having a bit of a moment. The game I’m playing, Cairn, is just the latest in a handful that have been released in the last few years. Mostly the province of small and independent game studios, climbing simulators range from fantasy-oriented (Jusant) to hyper-realistic (New Heights). And climbing is a major part of popular adventure games like Uncharted, Tomb Raider, and The Legend of Zelda. Though to be fair, the ascents in those games have about as much to do with real climbing as Indiana Jones has to do with real archaeology.

Decisions, decisions, decisions. Photo: Screenshot, ‘Cairn’

As a long-distance backpacker, mountain biker, trail runner, skier, and general interest outdoor journalist, I often come into contact with (and write about) climbers. I’m also an avid consumer of adventure stories, which means I burn through the mountaineering and climbing shelf at my local library pretty quickly.

But I’ve never been one to limit my hobbies to one or two categories, and I’ll happily blast aliens in shooters (Halo), strategize with friends in fantasy role-playing games (Balder’s Gate 3), or sneak around in stealth-based historical settings (Assassan’s Creed).

The experiment

And so before picking up Cairn, I had a lot of curiosity about climbing games. Mainly, who are they for? I recognize I’m somewhat of a weirdo in the outdoor adventure world. A lot of people with an outdoor sport pursue it at every opportunity and do limit their other hobbies, especially if they want to excel. They also talk about their sport endlessly (if you’ve ever chatted up a climber at a party, you know the word “beta” is always only two sentences away.)

So it’s hard to imagine a serious climber trading cliff time for a darkened room. It’s equally hard to imagine a gamer used to the flowy, absurdly unrealistic climbing mechanics of most video games enjoying a climbing simulator’s more grounded approach. I, an outdoor enthusiast with limited climbing experience and a side hobby as a gamer, might just stand in the middle ground.

So, I downloaded the Cairn demo to find out.

Backpacks and robots

The story is simple — a climber named Aava has her sights set on the first summit of the fictitious Mount Kami. That’s pretty much it. Get Aava to the top. How you get there is more or less up to you, as my adventure with the smooth granite face showcased.

There are some anachronisms. For one thing, Aava is wearing not a stitch of sponsored gear. Frankly, that comes as a relief to someone who watches as many climbing films as I do. Instead, she’s decked out in strange arm and leg wrappings, looking for all the world like an athletic Egyptian mummy. Her pack appears to be of the antique canvas and buckle variety. It’s also huge. You really have to admire her raw strength, if not her packing skills.

She also has a little robot helper who takes phone calls and retrieves pitons after she reaches safety, which I imagine would be handy in real life and probably isn’t as far away as you think it is, technology-wise. For some reason, this robot, who was supposed to be belaying me, let me fall to my death at least twice. I haven’t decided if it’s a bug in the demo or the developer’s way of imparting the (admittedly sound) advice that you shouldn’t trust robots.

A perfect piton placement. Photo: Screenshot, ‘Craig’

One limb at a time

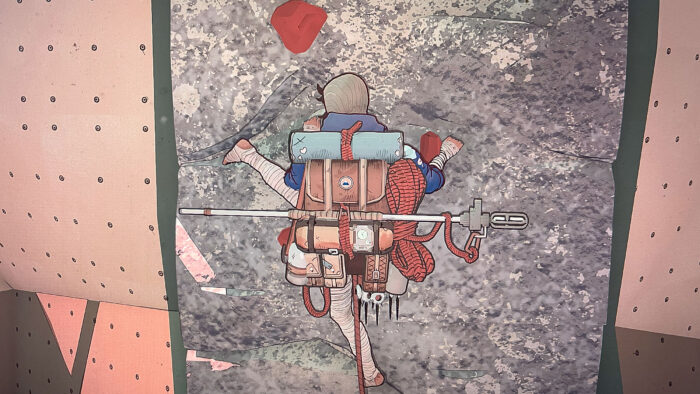

But beyond that, Cairn is as probably as close to real climbing as you can get without actually climbing. The game lets you control one limb at a time, and you’ve got to scan the rocks for cracks, ledges, handholds, and toeholds, then carefully reach out for them.

There’s no flashing red screen or timer bar to let you know when you’ve overextended Aava’s capabilities, just body animations and sound effects to indicate she’s growing taxed. You can use chalk and shake Aava’s hands out. You can drive in pitons and give her a break. Put a foot on a dodgy hold, and Aava will slip right off it. Gain a relatively safe ledge, and she’ll sigh in relief.

The thrill of rock

My general familiarity with climbing books and films served me well while playing. On one occasion, I was stuck until I looked around and noticed a vertical crack running for a few meters above my head. I stretched, got a hold, and crack-climbed. If I knew nothing about climbing, I might not have known that was possible. Instead, I felt for all the world like the rock-climbing protagonist in a memorable scene from Dan Simmons’ silly but nevertheless highly enjoyable sci-fi climbing novel The Abominable.

A bite of Kvikk Lunsj-adjacent candy inside my character’s suspiciously roomy tent. Photo: Screenshot, ‘Craig’

Cairn’s animation is also nicely dialed in, with Aava’s movements — the way she reaches out, feels the stone, gets herself into positions, and uses holds — immediately familiar and realistic. There are also some nice little nods to broader outdoor culture. In my few hours playing the game, the only food items Aava has in her pack are noodles and a candy bar that looks suspiciously like the Norwegian chocolate bar Kvikk Lunsj. The developers certainly did their research. Things feel pretty real. Most of the time.

If you can pull off this move, you are a better climber than I. Then again, almost everyone is. Photo: Screenshot, ‘Cairn’

One notch too risky

There was a time, perhaps somewhere halfway through my second or third readthrough of the Jon Krakauer oeuvre, that I thought I might take up climbing. I spent a year at my local bouldering gym before admitting that with a stocky build and shorter-than-average arms, I’m better suited to sports that use gravity rather than fight it. Also, it felt maybe one notch too risky for the expectant father that I was at the time.

But I remember what it felt like to succeed on a line that I thought was beyond me, the thrill of topping out, the frustration of slipping on a hold I thought I had on lock, the excitement that built just before a risky move.

Absurdly, Cairn recreates all these feelings, albeit without the attendant benefits of moving more than your fingers. The game is hard, slow, and frustrating. It’s also a lot of fun, so much so that I had to force myself to stop playing and start writing, lest my editor never get this story. And that dichotomy, maybe more than any other element in the game, is what really feels like real climbing.

Sweaty palms

All of which takes me back to my original question.

Who are climbing simulators for?

I’ve long suspected that most climbers look at climbing-specific video games with a bit of animosity, if not downright loathing. In addition to being a poor substitute for real climbing, I imagined they’d feel frustrated by the details gotten wrong, the movements glossed over, the terminology mangled. An unofficial straw poll of my climbing acquaintances proved me right — they were mostly uninterested in climbing games. Some were openly antagonistic to the very concept.

My character takes a breather and glances at her mangled hands, the result of a little crack-climbing. Photo: Screenshot, ‘Craig’

But that might be changing, in part because climbing simulators like Cairn are getting better at getting those details right. My friend and colleague Sam Anderson, climber and writer of many excellent ExplorersWeb stories, told me he’s recently changed his tune.

“I’ve been meaning to try a climbing game. Some of the crust has flaked off my opinion that they are wack, invalid, etc. I no longer feel the impulse to shit on them in any conversation in which they come up,” he said.

The gaming crowd

As for the gaming crowd, well, there certainly seems to be an audience. For one thing, developers pay close attention to trends and download numbers, and new climbing games wouldn’t keep being released if every single one was tanking. Jusant, for instance, has nearly 3,000 “very positive” reviews on the Steam platform.

But perhaps the real audience for Cairn and games like it is, well, me and others like me. I’m fascinated by climbing and mountaineering; I read the books, attend the film festivals, and spend a lot of time internally dissecting the motivations and powerful impulses that propel climbers upward. At the same time, I’m quite happy with my current sports and their risk/safety quotients. I have no desire to have a friend stand at my funeral and say, “He died doing what he loved.”

Instead, I’m satisfied, pleased even, to dip a toe into the world of granite and clouds safely from behind my computer. In that sense it’s not all that different from reading a climbing book or watching a film, two activities that many non-climbers participate in.

The drawback? Cairn isn’t a real story. The benefit? You feel, at least in some ways, like you’re doing something you know you’ll never do in real life. Sweaty palms and all.