In 1967, Mount McKinley (Denali) witnessed two pivotal moments in mountaineering history.

In February, a group of climbers embarked on a grueling quest for the first-ever winter summit. Five months later, a sudden, violent storm tested another team, resulting in one of the worst tragedies ever on a North American peak.

In this two-part series, we revisit these two 1967 expeditions. This is Part I, the story of McKinley’s first winter ascent.

(Writer’s note: Following the Associated Press style guide, I will use the name McKinley in these pieces.)

McKinley. Photo: Shutterstock

McKinley’s first ascent

North America’s highest peak, McKinley (6,190m) is located within the Alaska Range in Denali National Park.

It was first summited on June 7, 1913, by a team led by Hudson Stuck and Harry Karstens. Walter Harper and Robert Tatum were key team members. Harper, a young Athabascan climber, first stepped onto the summit. Harper insisted on calling the mountain Denali.

The first summiters followed the Muldrow Glacier route, approaching from the northeast and continuing along Karstens Ridge and the Harper Glacier (both named later).

The Muldrow Glacier. Photo: NPS

First ascent of the West Buttress

A team led by Bradford Washburn made the first ascent of the West Buttress route on June 17, 1951. This expedition marked a significant milestone, as the West Buttress became the most popular and accessible route to the summit.

Washburn had explored and photographed the route in the 1940s, identifying the West Buttress as a less technical alternative to the Muldrow Glacier. It required mostly snow and ice climbing but was still challenging because of crevasses and weather risks.

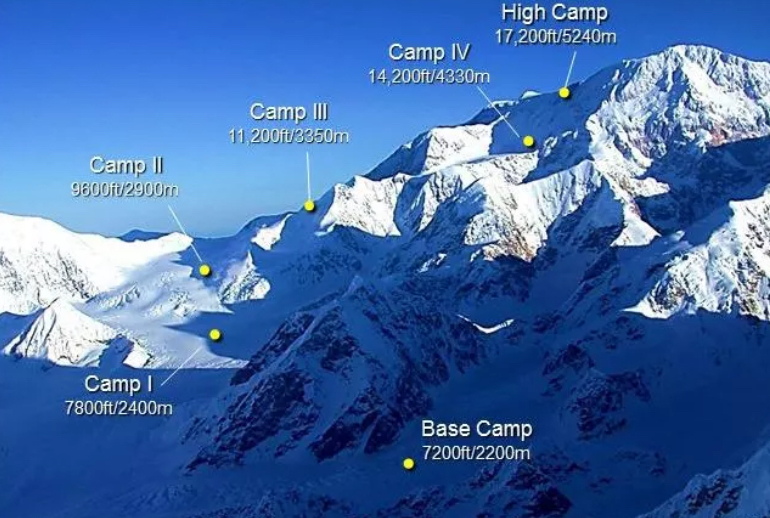

The West Buttress route approaches the mountain from the southeast, starting by landing on the Kahiltna Glacier in a small bush plane. The key features are the West Buttress ridge, Windy Corner, and the upper slopes near Denali Pass.

By the end of 1966, McKinley was still unclimbed in winter.

View of the upper area of the Kahiltna Glacier. There is roughly 4,000m between the foreground and McKinley’s summit. Photo: Swisseduc

The 1967 team

In 1965, Art Davidson and Shiro Nishimae from the Osaka Alpine Club began to explore the idea of a McKinley winter attempt.

The Winter 1967 Mount McKinley Expedition consisted of eight climbers: U.S. climbers Gregg Blomberg (leader), Art Davidson, Dave Johnston, John Edwards, and George Wichman, Shiro Nishimae of Japan, Ray Genet of Switzerland, and Jacques Batkin of France.

Many climbers of the era believed a winter climb of McKinley was impossible. But these eight mountaineers relished the idea of facing the cold, lack of light, storms, and bad weather.

Pilot Don Sheldon dropped them on the southeast fork of the Kahiltna Glacier on Jan. 29, 1967.

The team prepares to set out. First row, from left to right: Art Davidson, George Wichman, Gregg Blomberg. Second row, from left to right: Shiro Nishimae, Jacques Batkin, Dave Johnston, John Edwards, and Ray Genet. Photo: George Wichman

Starting in good spirits

The climbers would face the West Buttress route. “[We felt] that the lack of technical difficulty would be compensated for by the weather,” Blomberg recalled in his report for the American Alpine Journal.

It’s important to note that the route certainly isn’t easy. The elevation gain from base camp to the summit is more than on most 8,000m peaks.

Blomberg’s party started the climb unroped on the flat open expanse of the Kahiltna Glacier. They would resort to roping up when conditions warranted it.

The team atmosphere was great from the beginning.

“The darkness of our first night was no match for the intense happiness and comradeship inside the tent,” Blomberg wrote. “Our laughter spilled out onto the snow with the light of the Coleman lanterns. The jabber of the group in their many accents was music to my ears.”

No shortage of crevasses. Photo: Swisseduc

Tragedy strikes

Progressing toward one of their first camps, each climber kept his own pace. In a moment, Davidson fell into a crevasse. Fortunately, he was unhurt.

“The small hole my body had punched in the surface of the glacier was the only indication that a crevasse, probably a whole system of crevasses, sprawled before me,” Davidson wrote.

The climbers try to rescue Batkin from the crevasse on the second day of the expedition. Photo: Art Davidson

On January 31, tragedy struck. While part of the team reached their new campsite and started to set up, they realized that Batkin had disappeared. Batkin had been carrying a load to camp when he fell into the same crevasse that Davidson had narrowly escaped earlier.

The team tried to help Batkin, but he had died in the fall, and several resuscitation attempts failed.

The West Buttress route on McKinley. Photo: NPS

“That evening, there were seven of us in the two tents, yet how very alone each of us felt,” Blomberg wrote.

The team was about to quit the expedition. However, after meditating, they wrote a press release as follows: “Jacques Batkin died in the pursuit of a winter ascent in which he truly believed. We will continue the attempt with his spirit and presence very much in mind.”

Progressing on the route

Later, Edwards also had a close call when he fell into a crevasse in an area they considered safe. Fortunately, he was tied to one of his partners, and the rope caught him.

After a few stormy days, they had more than a week of good weather and established Camp 3: a three-unit igloo-plex below the Kahiltna Pass at about 3,000m. Kahiltna Pass marks a key milestone; it is often where teams establish an early camp and is a transitional point on the West Buttress route between the lower glacier and upper basin.

Traverse to Denali Pass. Photo: NPS

By the end of the eight days of good weather, the party had set up Camp 5 at about 4,300m. At this camp below the West Buttress, the climbers built two igloos almost entirely above the snow, with entrances below floor level. Because Camp 5 lies in a south-facing basin, it receives the brief but beautiful winter sun.

Over the next two days, they had to wait out the poor weather before continuing. The climbers progressed gradually and reached 5,240m. There, they established their highest camp. First, they used a tent, and later, they dug a snow cave into almost rock-hard snow. This camp would be key when returning from the summit.

Denali Pass

On February 26, the climbers left Camp 5. From the ridge, they ascended to Denali Pass at around 5,547m. It is a high, exposed col, situated between McKinley’s main summit and the slightly lower South Summit.

Above Denali Pass, they saw that McKinley’s summit had clouded over, and 300m below, they stopped to discuss their options. The climbers decided to descend. But the weather tricked them. As soon as they reached their high camp, the peak cleared.

The next day, the five climbers set off again. After reaching Denali Pass, Nishimae and Blomberg prepared a bivy site for the others and returned to high camp.

Denali Pass is on the left. The photo is from an old NPS accident report. Photo: NPS

Summit

Davidson, Genet, and Johnston topped out on February 28 at about 7 pm. The three climbers grabbed each other in a three-way hug and shouted: “We made it!”

“We have looked forward to the view from the summit, but there was only darkness in every direction,” Davidson said.

Before descending, they hollowed out a hole in the snow and buried Batkin’s hat in tribute.

More trouble

By midnight, Davidson, Genet, and Johnston reached Denali Pass. There, they carved a small cave into the mountainside for shelter as the weather deteriorated. It was the beginning of a seven-day ordeal as they waited out a violent storm.

By now, the expedition was split. Blomberg, Nishimae, Edwards, and Wichman were at 5,240m and had no way to communicate with the three summit climbers.

On March 1, Blomberg and Nishimae tried to reach Davidson, Genet, and Johnston but could not progress far in the hurricane-strength winds.

“The fury of the storm made it suicide to go further,” Blomberg recalled.

There was no option but to keep faith that the storm would eventually weaken. For now, both groups were trapped.

A snow cave on McKinley. Photo: Pete Thomas Outdoors

Recipe for survival

There is no concrete recipe for how to survive a storm at altitude. Davidson, Genet, and Johnston’s only sustenance was courage and determination.

“We were exultant, not from any sense of conquering the wind, but rather from the simple companionship of huddling together in our little cave while outside in the darkness, the storm raged through Denali Pass and on across the Alaska Range,” Davidson said.

For the three trapped climbers, the low air temperature outside their cave combined with the intense wind to create a windchill equivalent of -100ºC. Fatigue and frostbite took hold, and they were about to run out of food.

Descent

On the fourth day, Blomberg and Edwards began their descent from high camp. They hoped to get a helicopter back to the Pass at the first opportunity. The two climbers reached Camp 5 on March 5 and later arrived at Base Camp and radioed out. Meanwhile, a whole series of rescue operations began.

After a week, the storm had finally stopped, and on March 7, an army plane sighted three climbers descending Denali Pass. Davidson, Genet, and Johnston were alive.

The three spent the night at Camp 5. The next day, military helicopters plucked them from the peak, along with Edwards and Blomberg, and flew them to Talkeetna. Rescuers also picked up Nishimae and Wichman from Camp 3 on March 9.

Aftermath

Genet became an important figure in the development of commercial expeditions to McKinley. But he died on Everest on Oct. 3, 1979, while descending from the summit with a client. Both died of exposure, exhaustion, and frostbite.

Ray Genet. Photo: The High Expedition

On June 21, 1991, Genet’s son, 12-year-old Taras Genet, became the youngest person to summit McKinley.

Ten years later, on June 17, 2001, Galen Johnston, son of Dave Johnston, summited McKinley at age 11 with his parents. He still holds the record for the youngest person to summit McKinley.

Art Davidson has written an account of this expedition called Minus 148 – The First Winter Ascent of Mount McKinley, which is well worth reading.

We will publish Part II tomorrow.

Photo: Denali National Park and Preserve