In September of 1573, authorities in the Franche-Comté region of now-France declared open season…on werewolves. The edict raised the alarm about a werewolf on the loose. Villagers reported that children had gone missing, and they thought a werewolf was to blame.

The parliament agreed, and they agreed far enough to pause previous edicts that banned citizens from gathering in large groups and carrying weapons. Armed with their newly legal halberds, pikes, long guns, and cudgels, the people of Franche-Comté sallied forth.

A 17th-century werewolf hunt, depicted in a woodcut. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

What is a werewolf?

You may think you know what a werewolf is. You’ve seen movies. A person who was bitten by a werewolf is cursed to turn into a wolf-man hybrid every full moon, when they run through the woods (or London) in a state of mindless animal violence. But that creature is a much more recent creation; the werewolf of the 16th and 17th centuries was an entirely different animal.

To the people of early modern Europe, the werewolf was a person, usually a man, to whom a demon had given the power to transform into a wolf. The wolf transformation was triggered by an item of clothing the werewolf put on, like a wolfskin belt or cloak, or by applying a special ointment.

Second only to transforming into a wolf, the defining trait of the early modern werewolf was cannibalism. The eating of a fellow person was one of the ultimate taboos of the period. It was invoked as a potent symbol of “otherness” and the violation of cultural norms. Jewish people, Mongolians, pre-Christian Celts, and Indigenous Americans were all depicted as cannibals, as were witches.

Witches and werewolves overlapped considerably, and it’s difficult to draw a firm line between the two categories. Some demonologists of the period, like Henri Boguet, believed the werewolf was an especially dangerous kind of witch. As time went on, the werewolf and the witch blurred together. In fact, the more blurred the distinction, the more often female werewolf cases appear.

But at the height of the werewolf panic, they were a distinct class of religious criminal, and were nearly always male.

This woodcut shows a werewolf from Geneva who was convicted of killing and eating 15 children and burned alive in 1580. Photo: Zentral Bibliothek Zürich

Why did people hunt werewolves?

Even today, there are occasional panics over wolf attacks, real or imagined. But in early modern France (and into Switzerland and Germany) wolf attacks were an actual threat. Many of the missing children and ravaged bodies that appear in werewolf records were probably victims of wolf attacks. In North America, genuine wolf attacks are almost unknown, but in Europe, the animals had ample opportunities to acquire a taste for human flesh by feeding on battlefield corpses. So attacks in Europe sometimes had substance to them. However, the local authorities weren’t calling for wolf hunts. There were hunting werewolves.

In many ways, the people of 16th and 17th-century Europe imagined the werewolf as the ultimate violator of cultural, moral, and religious norms. But unlike their racist imaginings about pagan cannibal foreigners, the werewolf was an enemy within. It’s no coincidence that werewolf and witch paranoia came at the same time as the Protestant Reformation.

Imagine the innocent WASP suburbanite of the 1950s threatened by hidden aliens in Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956). Only, instead of secret communists, it’s secret Protestants. Or, in a Protestant country, secret Catholics. This was also a period of changing economic and social systems, where poverty became a major social concern and began to be associated heavily with sin and crime.

At the same time, countries were getting bigger and governments were getting more involved in people’s personal and religious lives. How does a government, secular or religious, demonstrate and enforce its new power? By persecuting and prosecuting the embodiment of everything that wasn’t allowed.

While some accused werewolves may have been actual human murderers, most deaths were likely due to wolf attacks. Photo: Shutterstock

The Inquisition inquires about werewolves

The 1573 hunt wasn’t the first incidence of werewolf fervor in the French region. Fifty years earlier, the first werewolf case was prosecuted — by the Spanish Inquisition.

While Franche-Comté, situated in a forested and mountainous region next to Switzerland, is part of France today, in the 16th century it was owned by the Spanish Habsburgs and was subject to the Inquisition.

So in the winter of 1521, papal representative Jean Boin traveled to the small town of Poligny. Poligny had a werewolf problem; two of them, in fact, named Pierre Burgot and Michel Verdun. Boin extracted a confession from the pair, detailing their strange crimes, as follows.

Several years ago, they had given their souls to the devil in exchange for various promised gifts. These included a bag of money which, Burgot complained, the devil had failed to deliver. He did give them an ointment which allowed them to turn into wolves, though. As wolves, they ran freely through the countryside, copulating with female wolves and eating several children.

One contemporary, 16th-century physician and skeptic Johann Weyer, pointed out a number of inconsistencies in the account. In one example, they claimed to have swallowed up a girl whole, except for her arm. Later, however, they claimed they had only eaten a little of her. Weyer believed that the experiences they described were imaginary, coming from hallucinogenic drugs in the ointment or some kind of mental illness.

The court didn’t agree: Burgot and Verdun were convicted and burnt to death.

An auto-da-fé of the Spanish Inquisition and the execution

Who gets to hunt the werewolves?

After Burgot and Verdun, the hunt went cold for several decades. Then in 1551, another Inquisitor found himself making the trek to rural Jura. Inquisitor Symon Digny heard the confession of a man named Pierre Tournier, who claimed to have murdered fifteen people. The Inquisitor charged him with werewolfery and witchcraft, and charged his wife and sister as conspirators. All three were burned alive at the stake.

The Parliament of Dole was horrified. Not by the burning-at-the-stake thing, they did that themselves all the time, but by what they believed was an infringement upon their right to prosecute criminals. The Parliament complained that the Inquisitor had failed to properly inform or cooperate with authorities. It insisted that from then on, they would be doing the prosecuting, thank you very much.

So when rumors of a werewolf snatching up children began to circulate in the early 1570s, the Parliament of Dole jumped at the opportunity to enforce its new authority. That’s how we got to the September 1573 edict, which launched a werewolf hunt.

Today, a parliament is usually a legislative body, but in the ‘Ancien Régime’ French system, it was judicial. This painting of the Parliament of Paris convening shows what a session might have looked like. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The Hermit of Dole

Giles Garnier was “the Hermit of Dole,” an immigrant from Lyons, living in near-isolation with his wife Apolline in the forest hermitage of Saint-Bonnot. The Garniers lived in extreme poverty and weren’t integrated into the local community. Authorities arrested him in 1573; they had found the werewolf they were hunting.

Garnier reportedly confessed readily, repeatedly, and without the use of torture. Even if that’s true, it’s impossible to know how much coaching he received. Possible coaching aside, the story he ended up telling went like this:

Starving, Giles Garnier was roaming the woods in search of food when he met with a mysterious figure, described only as a “phantom.”

This phantom offered him an ointment that allowed him to transform into a wolf when applied. As a wolf, the phantom promised, Garnier would be able to hunt for food, saving himself and his wife from starvation. Garnier accepted the ointment.

According to his arrest record, he used this power to kill and eat several children while in the shape of a wolf. He also took some of their flesh to feed to his wife. Scandalously, they even ate this meat on a Friday. One would think even the devoutly Catholic authorities would consider “eating meat on a fish day” to be burying the lead a bit in this case.

The record includes times and locations of the murders, some of which occurred over sixty kilometers from where Garnier, an older man in poor health, was living. Nevertheless, he was burned at the stake in 1573 on the authority of the Parliament of Dole.

This engraving by Lucas Cranoch the Elder depicts a cannibal werewolf. Photo: The MET Museum

Henri Boguet and the Loupgarou menace

Perhaps the most prolific werewolf hunter was a demonologist and legal scholar named Henri Boguet. Thanks to his expertise and zeal, in 1596 Boguet became the grand judge of the Saint-Claude region of Franche-Comté.

He got right to work rooting out the scourge of demonic influence he believed infested his new domain. Boguet was convinced that witchcraft and werewolfery were everywhere, heralding the imminent coming of the end times.

During his tenure, Boguet tried 38 people, condemning 28 to death by burning. Burning at the stake was usually just for show; the victims were strangled to death beforehand, saving them the long agony of burning. Werewolves were one of the few groups that were always burned alive.

Throughout 1597-98, Boguet uncovered (or created) a hidden society of werewolves. It started with Jacques Bocquet. Bocquet was a “cunning man,” a sort of folk healer herbalist. A woman accused him of witchcraft, and he then accused her of the same. She never confessed, but Bocquet did. Not only was he a witch, he admitted, he was a werewolf — and he wasn’t the only one.

Bocquet named names who named names. All of them, the account went, ran together with the devil as wolves, attacking livestock and children. They were all desperately poor people, leveraging their diabolic power for revenge against their tormentors. As wolves, Bocquet and his followers attacked people who had previously beaten them or denied them food and alms.

Nearly all of Boguet’s werewolves were condemned and burned alive. But not every werewolf case ended in execution.

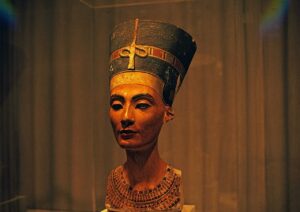

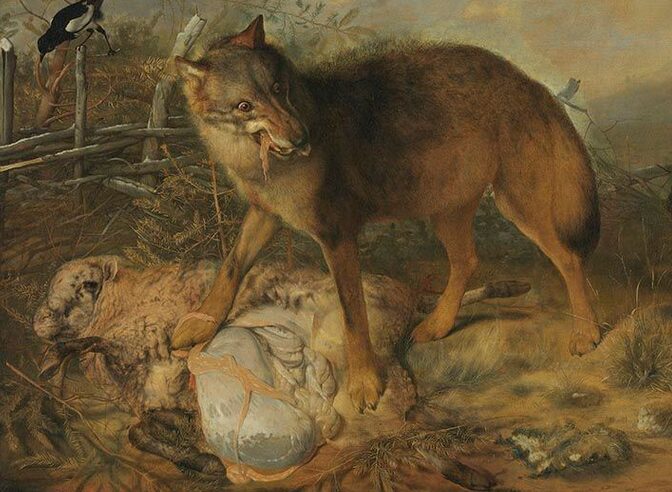

Werewolves were also accused of killing and eating livestock, a serious crime. The loss of an animal could make the difference between life and starvation for the rural poor. Photo: ‘Wolf reißt ein Lamm’, 1666, Wikimedia Commons

The madman Werewolf of Angers

In the same year, a guard of the Provost of Angers found a man lying prone by an abandoned house. The man was “hideous, and very hairy, with an evil stare.” He fled, but not long after this odd encounter, the guard saw him again — being dragged into town, tied to a cart. Inside the cart was the bloody body of a teenage boy.

The man was Jacques Roulet. The guard asked him if he was the man he’d seen in the forest. Roulet said yes, and also, by the way, he was a werewolf and had killed and eaten the boy in the cart.

He was immediately arrested and brought to Angers for trial, where Chief of police Pierre Airaut examined Roulet and the remains. The boy’s body was partially eaten and had claw and tooth marks from a “beast.” Roulet himself was an alarming figure, with bloody hands and teeth. He had long fingernails and a hard, distended belly, presumably from gorging on flesh.

Roulet wasn’t shy about telling his story. He was about thirty years old and lived with his parents and three siblings in a village nearby. Roulet implicated his entire family; according to Roulet, his brother Jean and cousin Julien went out as wolves with him and had helped him kill the young boy. They transformed using an ointment that his parents had given them.

Roulet was condemned to death, but not executed. Instead, his case was appealed to the Parliament of Paris.

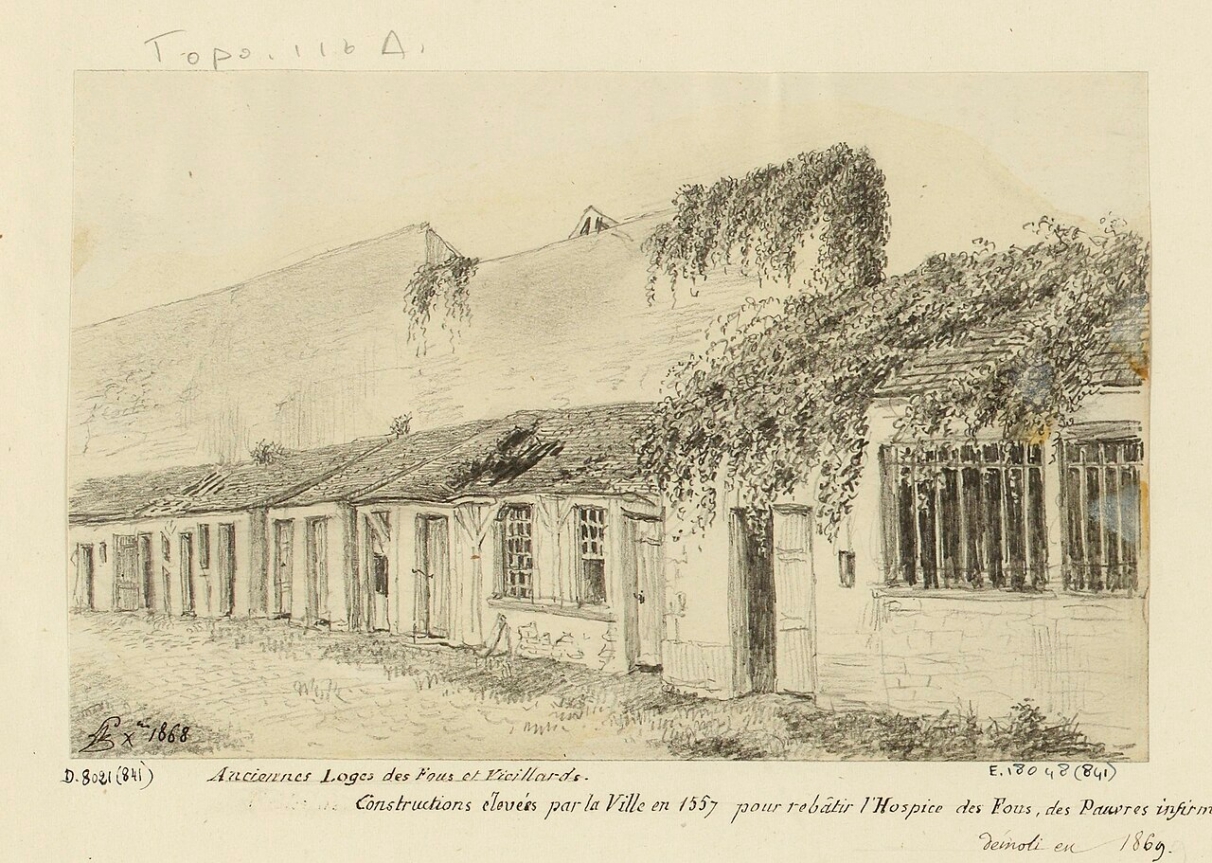

“There was more insanity in this poor, miserable idiot than there was malice or witchcraft,” they decided. Roulet was sent to an asylum for two years, after which he disappeared from the historical record.

A sketch of ‘la maladrerie Saint-Germain’, where Roulet was sent. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The strange case of Jean Grenier, child werewolf

In 1603, a series of wolf attacks on both livestock and children rocked the small settlement of La Roche-Chalais. Then a 13-year-old shepherd girl named Marguerite Poirier, the victim of one attack, came forward with an accusation: a werewolf was responsible, and she knew who it was.

She’d been out in the fields with two other teenage girls when a wild-looking boy approached them. He asked them if any of them would marry him, and when they rejected him, he grew upset. Attempting to impress or intimidate them, he claimed he could turn into a wolf. Then he escalated his claims; not only was he a werewolf, but he had killed and eaten a number of children. In fact, he was the wolf who’d attacked Marguerite a few weeks prior.

They arrested the boy, named Jean Grenier. Grenier was about thirteen, but looked and acted younger. He had been roaming the countryside, begging, having left home after a severe beating from his father, Pierre. Pierre featured prominently in Jean’s testimony, which was extracted in confused fits and starts after a period of imprisonment.

Jean transformed into a small red wolf using a wolfskin he had received from a demonic figure named Pierre Labouaut. Labouaut, Jean said, lived in a black house in the woods where people were boiled in pots and roasted on spits. His father had introduced them.

Together, Jean and Pierre had run as wolves and killed and eaten livestock and a young woman. But two years before, Jean’s stepmother had found out about the werewolves and left them. Since then, Jean opined, his father didn’t hunt with him.

A werewolf attack depicted in 16th-century woodprint. Photo: Google Arts and Culture

A family affair

Investigators had Grenier recreate his crimes, likely further feeding into the fantasies of a mentally vulnerable young boy. After his initial confession, Jean broke down sobbing. He described attacking Marguerite, as well as breaking into a house and devouring an infant, and repeatedly accused his father of being complicit.

But when the judges brought father and son face to face, Jean froze. Seeming confused and frightened, he failed to accuse his father. When he was interviewed privately, he repeated his accusation, and after a second confrontation, he managed to face his father and level the charge of werewolfery directly. His initial wavering, however, led to Pierre’s release. Despite Jean’s best attempts, his father wasn’t prosecuted.

Jean was, but “the court, in the end, took note of the age and imbecility of this young boy, who is so stupid and mentally impaired, that children of seven or eight normally show more reasoning than he.” Instead, he was sent to live out the rest of his life in a monastery.

It was in that monastery, several years later, that he met juror and demonologist Pierre DeLancre, writer of the above quote. DeLancre interviewed Jean, then twenty, though still small for his age. Jean said that he still craved human flesh, but had learned to reject the devil, who no longer came to visit him.

DeLancre concluded that it was a mistake to let Grenier live. He personally had sentenced dozens of witches to death, and though he admitted Grenier was young, poor, and mentally disturbed, it set a bad precedent.

A depiction of the witches’ sabbath, included in Pierre DeLancre’s 1612 book. Jean claimed his father had taken him to the sabbath at age ten. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The end of werewolf hunting

Perhaps DeLancre was right about setting a precedent, but as time went on, officials and theologians became skeptical of whether werewolves even existed. Among everyday people, the concept became increasingly watered down.

In the Netherlands, werewolfery was just another activity of witches. In 1696, local courts saw a case where one woman’s geese ate the cabbage from a neighbor’s garden. The neighbor attempted to chase them off, which the owner of the geese took offense to, thinking he was trying to steal them. She accused him of being a werewolf and he sued her for slander. He won the case and she paid one Reichsthaler in damages.

In Germany, “werewolf” became shorthand for a violent, angry person. In 1623, a man named Johan Wulner was accused of being a werewolf due to his habit of intimidating people with a halberd. Around the same time, his fellow townsman Goddert Kampmann attacked another man’s genitals with a fork. The man called him a werewolf, and Kampmann sued him for slander.

The Parliament of Dole stopped prosecuting werewolves in 1633, putting out an edict clarifying that they were just hunting regular wolves now. And witches still, obviously. Local courts that hadn’t gotten the news yet managed to catch a few more werewolves, like a beggar named Claude Chastellan, who was convicted in 1643.

The last werewolf trial was held in a remote village in 1663. Brothers Mathieu, Claude, and Ayme Mathieu were in court for a series of robberies, and a charge of werewolfery was tacked on as well. The brothers confessed under torture, but appealed to the Parliament of Dole.

The same body that had called for a werewolf hunt a century earlier overturned Mathieu’s sentences and declared the whole case bunk.