“Listen! Listen! Talk to me! I am hot!…oxygen…oxygen…am I going to crash?” For several decades, these chilling words, which screeched through a makeshift radio in the 1960s, have refused to fade. A choppy, distorted, and panicked voice of a woman in trouble was one of the many recordings which gave rise to one of the most persistent urban legends of the Space Age: the lost cosmonauts.

Believers in the lost cosmonauts reject Yuri Gagarin’s title as the first man in space. Their theory insists that the Soviets were secretly launching humans into space before Gagarin made his pioneering flight aboard Vostok I in 1961. The cosmonauts on these supposed earlier flights had all died.

Yuri Gagarin with medals. Photo: Mil.ru/Wikimedia Commons

The bond of brothers

It is four years after World War II. Italian brothers Achille and Giovanni Battista Judica-Cordiglia had a vested interest in radio technology. They spent their adolescence saving up to buy parts to make radio antennas. Along with other pieces of radio equipment that they bought from American soldiers, they built an enormous antenna, which they mounted on the roof of their apartment.

For fun, they enjoyed tuning into frequencies from around the world. However, one moment changed everything for them. When Russia successfully sent Sputnik I into orbit in 1957, it also launched the space race. In 1958, the United States followed with Explorer I. The brothers managed to capture the frequencies of both missions.

Achille and Giovanni wanted in on this space race in their own way, by eavesdropping. In a repurposed World War II German bunker just outside of Turin, where their parents had moved the family, they continued their radio work. Eagerly, they set up an experimental listening station, with their homemade radios tuned into happenings in the night sky.

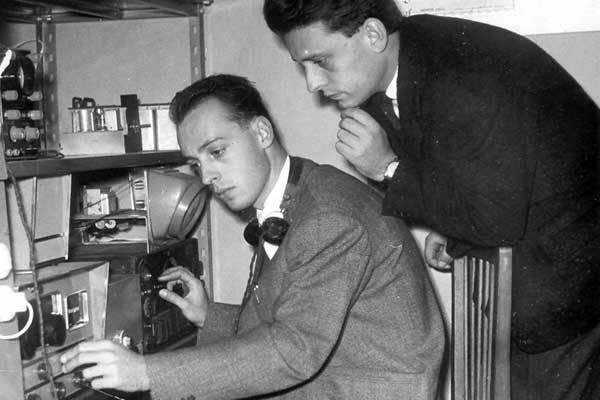

Achille and Giovanni Judica-Cordiglia with their radio. Photo: Unknown

A deadly discovery

For months, the brothers worked tirelessly to perfect their system to track all Soviet missions. One night, they held their breath as faint beeping started to come through their headphones. Morse code. More accurately, an SOS. They believed it must have been a manned launch that went wrong. However, at this time, only dogs were used on space flights.

The next odd occurrence was the sound of a human heartbeat accompanied by heavy breathing, most likely coming from a male in distress. After that, panicked transmissions from a team of three people (two men and one woman) said, “Conditions growing worse. Why don’t you answer?…Remember us to the Motherland! We are lost! We are lost!”

Over the years, such dire transmissions continued and further fueled the rumors that the Soviets were regularly losing their cosmonauts.

News outlets caught wind of the story, but it wasn’t the first of its kind. In 1959, an article from the Continentale in Italy claimed that a Czechoslovakian official gave a list of the names of cosmonauts who died during their missions: Alexei Ledovsky, Andrei Mitkov, Sergei Shiborin, and Maria Gromova.

Test pilots?

In a Soviet periodical called Ogoniok, Pyotr Dolgov and Ivan Kachur were declared dead, not during a clandestine mission to space, but after conducting a parachute test at high altitude. No one was able to confirm and clarify these details. This begs the question: Were these “cosmonauts” actually high-altitude test pilots or parachutists?

Achille and Giovanni’s discoveries did not escape notice. Soon enough, there was an ominous knock at their door from none other than the KGB. Writer Micah Hanks at The Debrief wrote that years later, a journalist named Kris Hollington tracked down a KGB visitor in 2008, who admitted:

“Of course, we were interested in the Judica-Cordiglia brothers; they were hacking into our communications. Imagine that today, a pair of amateur kids taking apart the Russian space program like it was a toy…”

To their surprise, the man let them off with a warning. Nonetheless, the visit itself was ominous and made them question whether or not the Soviets were trying to cover up or silence any interested parties.

The brothers’ work earned them a well-received visit to NASA headquarters, where scientists and communications specialists praised them for their inventions and self-taught knowledge. They also recorded John Glenn’s communications during his mission in 1962. Seeing their value, NASA and the brothers exchanged information, with NASA trading American mission frequencies for Russian frequencies. Achille and Giovanni established the Zeus Network, which allowed radio enthusiasts around the world to tap into spaceflights. This lasted until at least the 1969 moon landing.

Theories

Did the brothers actually overhear dying cosmonauts crying out to the ether for help? The many cryptic and terrifying jumbled cacophonies suggested a failing Soviet space program that could leave America the victor of this highly politicized race.

Some believe the brothers lied or exaggerated to gain notoriety. According to writer and science scholar Maria Rosa Menzio, the brothers received two kinds of translations from the mostly indiscernible recordings they intercepted. When they sent them to native Russian speakers, the translations made little sense. However, when they took the recordings to a German teacher who spoke Russian, the teacher only gave them what she thought she heard or was able to make out. Therefore, skeptics find the brothers to be an unreliable source.

Vladimir Ilyushin protrait. Photo: testpilot.ru

Space historian James E. Oberg provided his own take on the lost cosmonauts. Digging into some of the names, he claims to have clarified the story of one of the victims mentioned in Ogoniok. He said:

Dolgov, an experienced test pilot and stratospheric parachutist, really did disappear under mysterious circumstances about that time. More than two years later the Russians announced that he had just died in a high-altitude jump in November 1962.

He also quoted Dr. Charles Sheldon, a Washington expert on the Soviet space program, who said:

Those who would believe in these purported Soviet orbital deaths must think there is a second and independent Soviet manned program. In contrast to the open program which always brought the man back until 1967, the secret program always failed. Why the Russians would want to run a secret failure program parallel to their open success program is not clear.

Many real accidents

It is no secret that the Soviet space program had its share of bad luck. There were many accidents, probably more than we know, which were never made public. But most importantly, one of the main reasons why many people believe in the lost cosmonauts is the highly secretive and authoritarian character of the Soviet Union. Media, higher education, culture, and even thought were under heavy state control and censorship. No one truly knew what was going on. From assassinations and undercover operations to mysterious disappearances, it was always tempting to lean toward the theory of a big cover-up.

The behavior of Soviet leaders fomented further suspicion. Sometimes, Nikita Khrushchev teased at upcoming launches that they were ready to send men into space. Then nothing would happen, which made people believe the launches occurred but failed.

This brings us to another strange story. In the newspaper The Daily Worker, journalist Dennis Ogden wrote about a cosmonaut named Vladimir Ilyushin who was supposedly the first man in space. He launched two days before Yuri Gagarin’s flight, but his flight crashed in China, and he suffered severe brain damage. Officials claim Ilyushin was the victim of a car accident, while others say this was an excuse to explain away Ilyushin’s injuries.

The takeaway

The Cold War was a battle between the West and the East, but also a fight between what was real and what wasn’t. Truth and propaganda came head to head. It’s hard to get to the bottom of propaganda.

Oberg says:

The only safe answer still is that no one outside a small coterie in the USSR can know. We can say, however, that there is no hard evidence available to indicate that any such fatal secret missions ever took place…

As we examine the evidence, it is possible that the “lost cosmonauts” could have been a group of ill-fated high-altitude test pilots or parachutists who might have been destined to go into space one day. Unfortunately for them, they didn’t make it. In the craze of one of the world’s most intense periods, truth was sometimes mixed with fiction.