The Shroud of Turin is a length of linen cloth that believers argue is Jesus Christ’s burial shroud. The fabric appears to show the faint image of a man and wounds sustained during crucifixion. Until recently, researchers believed that documents from Champagne in 1389–1390 were the earliest reference to the shroud. But a new publication by Nicolas Sarzeaud in the Journal of Medieval History examines a fresh source from decades earlier.

Unexplained phenomena

In a treatise on unexplained phenomena written sometime between 1355 and 1382, Norman scholar Nicole Oresme investigates several mysterious physical and psychological phenomena, including the shroud. Orese takes a “naturalist’s approach” to the unexplained, seeking rational explanations rather than attributing them to God, demons, or unknown influences. In his research paper, Sarzeaud explains that Oresme refers to the shroud as “a ‘patent’ example of clerical fraud, prompting him to be more broadly suspicious of the word of ecclesiastics.”

This new source is important because it lends further weight to existing evidence that the shroud is a medieval fake. We know that when the shroud was displayed in 1389, the Bishop of Troyes subsequently denounced it as a fake. The Bishop called it “cunningly painted, the truth being attested by the artist who painted it.”

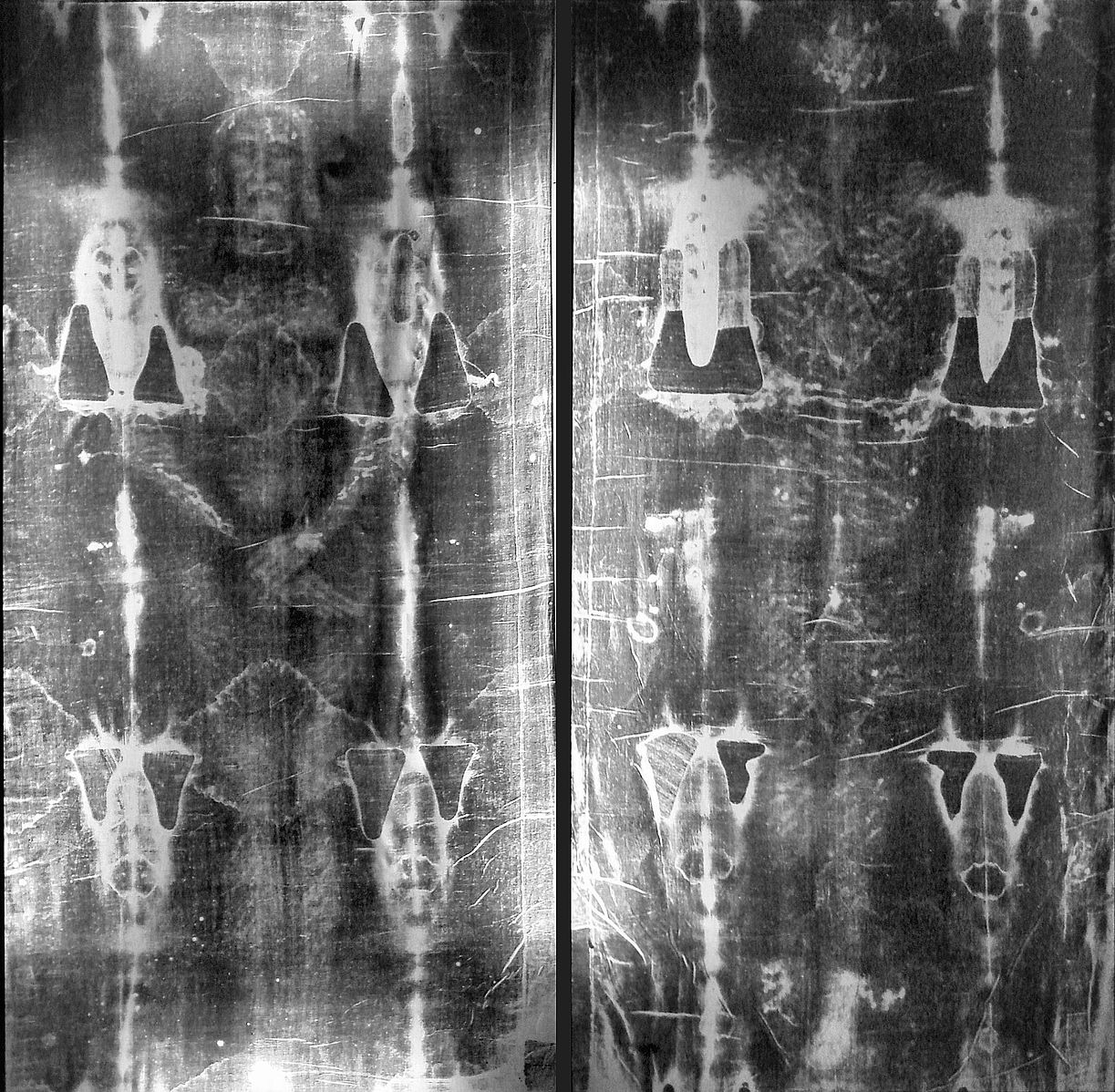

Full-length negatives of the Shroud of Turin. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

A representation, not a relic

Pope Clement VII also mentioned the shroud in a letter dated July 28, 1389, in which the cloth is referred to as a “figure or representation of the Shroud of our Lord Jesus Christ.” Sarzeaud argues that this indicates it is a devotional artifact rather than a relic.

Other medieval sources suggest there was already a tug-of-war during this period between those contesting that the cloth was the Shroud of Christ, and skeptics, including within the church. Bishop Pierre d’Arcis wrote to Pope Clement VII sometime in late 1389 to persuade him to reverse his decision allowing the Shroud’s display. Sarzeaud summarizes the Bishop’s letter below:

The document indicates that the cloth had appeared during the time of Geoffroy I and was displayed as the actual Shroud of Christ. Pierre d’Arcis’ predecessor, Henri de Poitiers, had conducted an investigation and exposed the fraud: The cloth had been crafted artificially, and certain individuals had been paid to fake miracles.

The Charny family then hid the cloth sometime around 1355–56, according to Pierre d’Arcis’ memorandum. It remained out of sight for 34 years or so. Then, in 1389, the Lirey party attempted to revive the cult, now calling the cloth a ‘figure or representation of the Shroud’ to gain authorization for devotion while leading worshippers to believe it was a relic.

An argument without end

Recent scientific studies of the shroud suggest someone created it at around the time we first see it mentioned in written sources. In the 1980s, three separate teams of scientists used radiocarbon dating on the shroud. Their results, published in Nature in 1989, “calibrated calendar age range with at least 95 percent confidence for the linen of the Shroud of Turin of 1260-1390 [CE].”

Yet, 36 years after carbon dating and nearly 700 years after Oresme’s treatise on unexplained phenomena first mentions the shroud as a forged relic, many Christians still believe the Shroud of Turin is genuine. The discovery of Oresme’s treatise is unlikely to change believers’ minds, but it adds fascinating additional context to a religious argument that shows no sign of abating.