The year 1916 was a fantastic summer on the Jersey Shore, if you liked the threats of war, polio, and a deadly attacker stalking the waterways. That was the summer that a series of strange, violent incidents forever changed the way humans saw sharks.

Decades later, the grisly string of attacks that terrified East Coast swimmers partially inspired a novel by Peter Benchley. The novel was adapted into the movie Jaws, the first summer blockbuster. It still frames our interactions with ocean predators.

The cultural impact has only grown, but the truth behind the attacks is still murky. Did they really ever catch the guilty shark? Was it even a shark at all?

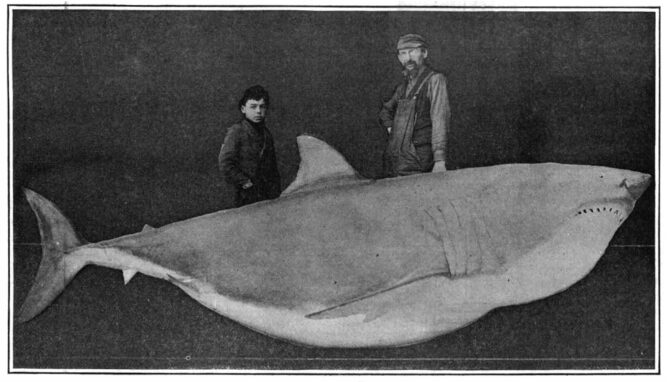

This shark was one of hundreds killed after a series of attacks. But was it a man-eater? Photo: The Richmond Palladium archives

A shocking incident

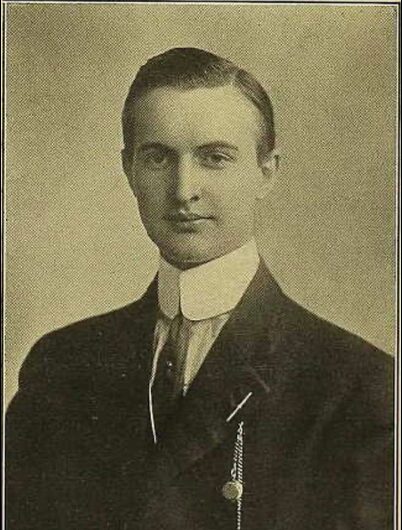

Nicknamed Queen City, Beach Haven, New Jersey, was a popular beachfront for well-off oceangoers. On July 2, 1916, crowds of people were out enjoying the sun and the water. One of them was Charles Epting Vansant, the 25-year-old son of a Philadelphia businessman.

Vansant was swimming fewer than 15 meters from shore, playing with a dog. Then, bystanders on the beach looked out onto the water and saw a fin cutting through the surf behind Vansant. They shouted out desperate warnings for him to swim to shore. Vansant listened and began to make his way back to the beach, but the pursuing fish was closing fast. A moment later, Vansant was pulled under.

In a stroke of fortune, one of the people on the beach was Alexander Ott, who had been a member of the American Olympic swim team in 1912. Ott took to the water and made for Vansant, but by the time he reached the struggling man, the damage was done. Nevertheless, Ott hauled a heavily bleeding Vansant back to shore.

His leg had reportedly been torn open, from thigh to knee. Vansant only survived for a few hours, dying that night in a nearby hospital. He was only the first.

Charles Epting Vansant, a few years before his death. Photo: 1910 Episcopal Academy yearbook

Blood in the water

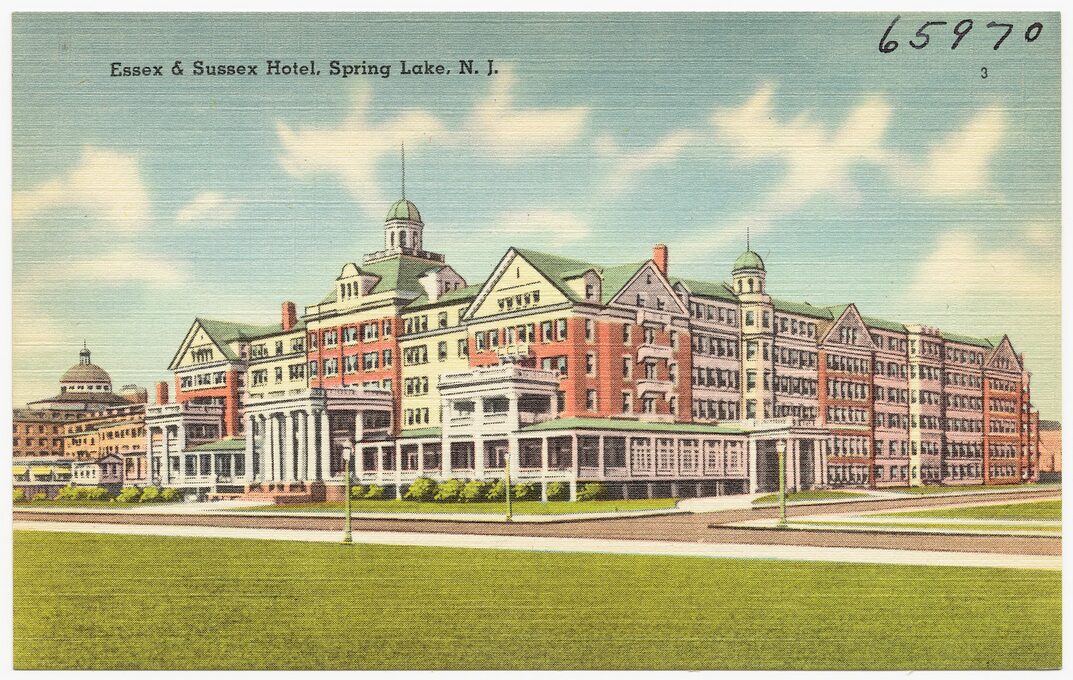

Vansant’s death was a strange tragedy, but it wasn’t enough to spark a panic. People were still enjoying the water in the middle of a hot July. But then on July 6, at Spring Lake beach, 32 kilometers away from Beach Haven, there was a second grisly incident.

Charles Bruder, a 28-year-old hotel worker and Swiss native, was swimming beyond the life lines at Spring Lake beach. Suddenly, lifeguards heard him cry for help. They quickly launched a lifeboat and began heading toward him, but before they could reach him, he cried out, and the water began to turn red.

A woman on shore, seeing the red shape, yelled that a red canoe had been overturned. There was no canoe; the red shape was Bruder’s blood. The lifeguards reached him only in time for him to name his attacker — a shark — and lose consciousness. When they dragged him into the boat, they realized in horror that both his legs had been bitten off, one above, the other below, the knee. There were also bite marks below his arm on his left side.

Lifeguards attempted first aid, but Bruder died of shock and blood loss right there on the beach. The community was shocked, especially the workers and guests at the nearby resort where Bruder had worked and was well known. According to a contemporary New York Times article, “Many persons were so overcome with horror… that they had to be assisted to their rooms.”

The Essex and Sussex hotel still stands, but its visitors today are unaware of the grisly tragedy that occurred over a century ago, on the very beach it overlooks. Photo: Boston Public Library Archives

Dire warnings up the river

While the Spring Lake community mourned, taking up a collection for Bruder’s mother back in Switzerland, local authorities took steps to prevent further attacks. Swimmers left the water, and a squad of boatmen began patrolling the coast to drive off any large sharks.

But preventive measures, it seems, were localized. Or maybe the boys who went to bathe and play at Matawan Creek thought they were safe. After all, they were several miles from the seashore, where the Coast Guard had reported huge numbers of sharks that very morning.

Lester Stillwell was an 11-year-old factory worker who’d left work with a group of friends to visit the creek. Around the time he was leaving work, at a nearby trolley bridge, retired sea captain Thomas Cottrell saw a long, dark shape gliding upstream with the incoming tide. Recognizing it as a shark, Cottrell ran to phone the barber, who was also the chief of police.

The chief dismissed it as a prank. Cottrell tried to spread the word himself, warning off one group of boys. Meanwhile, a group of teens who’d also seen the shark warned Lester’s group. According to Lester’s best friend, Albert O’Hara, they also thought it was a joke and went swimming anyway.

It was Albert who later felt something like sandpaper brush against his legs under the water. Then he caught a glimpse of something that looked like a submerged log. A moment later, Lester was pulled under the water.

The mouth of Matawan Creek. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

On a single tide

Realizing what was happening, the boys began screaming and ran for help. Stanley Fisher, a 25-year-old man who had been close by, came running and leaped into the creek. He dove down to the muddy bottom and emerged with the body of Lester, who was already dead. Before Fisher could even make for shore bearing the body, witnesses saw him scream and go under, as teeth tore into his thigh.

Two men in a boat were able to pull him from the water and take him to shore, as Lester’s body slipped from his arms. Ashore, a doctor who saw the wound estimated that ten pounds of flesh were missing from Fisher’s leg, but he was unable to see visible bite marks. The resulting blood loss and shock were too much for his body to bear, and he died that night.

But while doctors were still trying to save Fisher’s life, only about a kilometer away, 14-year-old Joseph Dunn and his brother were going for a swim with some friends. Thomas Cottrell, not yet aware of the tragedy which had already struck, was still trying to warn people. When he saw Dunn and the other boys, he warned them to get out. They started swimming for shore, but before they reached safety, Dunn was pulled under.

His elder brother and a friend dove back into the water. The submerged attacker released Joseph long enough for Cottrell to grab him and pull him to safety. Joseph, his leg mangled, was rushed to the hospital.

Reports of the grisly deaths flooded the papers. Photo: Philadelphia Inquirer, 1916

The great New Jersey shark hunt

Joseph had lost a lot of blood and was rushed into the operating room. That night, between emergency procedures, he refused to give reporters his home address. He didn’t want his mother to find out about his attack; he didn’t want her to worry. Against the predictions in the papers, Joseph not only survived but kept his leg.

The body of Lester Stillwell was found several days after the attack, a few hundred meters from the site of the incident. Witnesses said his small body had been bitten almost in half.

But even before Lester was found, a frightened and vengeful populace took up arms against what lurked in the water. The banks of the Matawan were lined with people wielding “rifles, shotguns, boat hooks, harpoons, pikes, and dynamite,” according to a contemporary newspaper. To prevent the killer from escaping, chicken-wire nets were stretched across the creek both above and below the attack site.

That stretch of creek was then shot into, stabbed at, and exploded with dynamite charges, but no sharks were killed. This was despite a handsome reward — $100 per shark — offered by the local authorities.

The coast itself swarmed with amateur shark hunters, who in the next few days managed to bring in several large sharks. But when their stomachs were cut open, they were exonerated post-mortem by the absence of human remains.

Locals on Matawan creek, ready to shoot any shark which dared show its toothy face. Photo: Public Domain

The culprit caught?

As experts debated the attacks, sharks took on a mythical status. The article quoted above went on to say that a shark’s thick hide “would hardly take an impression from buckshot,” and was even impervious to bullets. The doctor who treated Stanley Fisher, Dr. George Reynolds, reported that there had been a “poisonous liquid” in the shark bite, and it was the poison that had killed Fisher.

In the following weeks, vigilantes killed hundreds of sharks along the East Coast. The federal government budgeted $5,000 for eradication efforts and discussed sending in the Coast Guard.

Then, on July 14, eccentric local taxidermist and former lion tamer Michael Schleisser announced he had caught the Matawan Man Eater. As evidence, he produced a two-meter-long, 158-kilogram white shark. As appropriate to his profession, he promptly taxidermied it.

But first, Schleisser had scientists from the Natural History Museum examine it. Inside the shark’s stomach, they found what they believed to be human bones. The bones and the taxidermy shark were lost sometime over the past century, so it’s impossible to test them. However, it must be said that there were no further attacks.

This and many other great white sharks were hunted and captured after the attacks. But were they really to blame? Photo: Bronx Home News archive

Birth of a man-eater

In a culture saturated with the imagery and mythology of aggressive, man-eating sharks, it’s hard to imagine that we haven’t always looked at this particular fish family with terror. When we read that large sharks had been seen in the area before the first attack, we wonder why people were so slow to get out of the water.

In fact, the 1916 panic and the media reputation it inspired birthed our fear of man-eating sharks. Prior to 1916, most people considered them fairly harmless.

In 1893, a wealthy eccentric named Hermann Oelrichs, asserting the harmlessness of sharks, offered $500, about $18,000 today, to anyone who provided a verifiable shark attack story. Oelrichs also tested his assertion himself by jumping into the sea and swimming up to a three-meter-long shark. He emerged unharmed and never paid out the $500.

After the 1916 incidents, officials declared that they’d been wrong: sharks were man-eaters. Our new fear of sharks led to hundreds of millions of them being culled over the past century, threatening many keystone marine predator species.

Nowadays, we know that the truth is somewhere closer to our pre-1916 understanding. Sharks are usually indifferent to humans, and attacks, especially a series of attacks, are usually due to something like habitat disruption or learned behavior.

Rather than hungering for human flesh, most shark attacks are a case of mistaken identity. Mistaking a paddling hand or flashing jewelry for a seal or a silvery fish, sharks take an exploratory nibble. Even these are rare. There are about 64 shark bites annually worldwide, and less than a tenth of those are fatal.

A photograph of this impressive white shark specimen appeared in a 1916 Scientific American article on “man-eating” sharks. Photo: Scientific American archives https://www.jstor.org/stable/26014853

Was the great white framed?

When we discuss the “man-eating shark”, the first thought is the white shark, commonly known as a great white. It’s the shark in Jaws, the species of shark that Schleisser caught, and it’s the largest predatory shark species. But nowadays, many are skeptical that a white shark was the species behind the Jersey attacks.

While the white shark appeared on the suspect list at the time, contemporary reports mentioned the tiger shark just as often. A scientific write-up titled The Shark Situation in the Waters About New York names 19 shark species found in the area. Half a dozen of them could have been responsible for some or all of the attacks. These include hammerhead sharks, thresher sharks, brown or sandbar sharks, tiger sharks, and great white sharks.

One NYT letter to the editor proposed that it had not been a shark at all.

“I have spent much time at sea and along shore, and have several times seen turtles large enough to inflict just such wounds,” the writer claimed. Moreover, the turtle had “a vicious disposition.”

The white shark has become the byword for ocean-dwelling terror. But the reputation is far from deserved. Photo: Wikipedia Commons

Bull sharks actually the man-eaters?

Today, however, the top of the suspect list is the up to three-meter-long bull shark. While white sharks are actually rare in the area, bull sharks are somewhat less so. The key points in the bull shark’s favor are its reputation for aggressiveness and its ability to swim upriver into freshwater. A bull shark wouldn’t balk at swimming 18 kilometers upriver to the attack site, which would have been very unusual for a great white.

We know that bull sharks have been responsible for attacks in Australia, South Africa, Nicaragua, India, Florida, and more, with many incidents occurring tens of kilometers away from the open ocean.

But if there really were human remains in the stomach of Schleisser’s great white, there’s a good chance it was responsible for at least one of the attacks. Perhaps a great white killed the first two victims, on the beach, and a bull shark was responsible for the tragedies in Matawan Creek. Experts continue to speculate on which of these two species was most likely responsible. We will likely never know. It probably wasn’t a turtle, though.

While they are known for a pugnacious personality (thus the name) bull sharks aren’t inherently aggressive man eaters. Divers frequently swim alongside them in complete safety. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Sharks, submarines, and paranoia

Whichever species it was, the behavior it exhibited in 1916 wasn’t normal. Why the sudden rush of attacks? As with most animal attack stories, the answer was probably habitat disruption.

Even before the first bite, the public of 1916 was nursing a fear of what lurked beneath the waves. While America hadn’t yet joined WWI, Germany had engaged in a strategy of unrestricted submarine warfare. Germany’s infamous sinking of RMS Lucitania, a neutral U.S. passenger ship, only stoked submarine paranoia.

As well as contributing to the general atmosphere of maritime fear, many believed the submarine activity had led to the shark attacks. One letter to the editor expressed a common belief that “sharks may have devoured human bodies in the waters of the German war zone and followed liners to this coast,” which would explain “their boldness and their craving for human flesh.”

The sharks probably hadn’t become addicted to human flesh, but all the commotion of guns and torpedoes on the European side of the Atlantic may have led to increased numbers on the American side. They may have also been attracted to the ample food source offered by commercial fishing castoffs.

Coming full circle, after 1916, American political cartoons began depicting the submarine threat using shark imagery. Like with the millions of young men killing each other across the ocean, the Great War had turned peaceful coexistence into violent confrontation. If it were fiction, they’d call it too on the nose.