The history of exploration is replete with colorful characters: heroes and rogues, young and old, the brilliant and the mentally suspect. Little known, but one of the brilliant folks, is Canadian geographer David Thompson. Brilliant, but not without his quirks.

Unlike blues legend Robert Johnson, the alchemist Johann Faust, and Bernard Fokke, the reputed captain of the Flying Dutchman, Thompson did not make a pact with the devil. Instead, he reported playing checkers with the Prince of Darkness.

Thompson was born in London in 1770, educated at a school for poor and orphaned children, then studied further at Gray Coat mathematical school, an institution known for providing excellent mathematics, surveying, and navigational instruction.

At age fourteen, Thompson found himself in Manitoba as an apprentice clerk for the Hudson’s Bay Company. Later, he continued in their employ as a surveyor and cartographer in the fur trade. It was in his Churchill, Manitoba cabin that he supposedly entertained his sulfurous guest.

Meeting with the devil

By Thompson’s account, the devil walked in and challenged Thompson to a game of checkers — actually, several games of checkers, all of which Thompson won. Once defeated, the Spaniard-looking, short-horned devil simply disappeared. The experience made a lifelong, devout Christian of the young man, and the devil apparently made no further intrusions into Thompson’s amazing life.

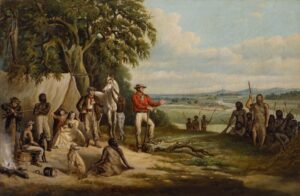

When he was seventeen, Thompson set off hiking and canoeing his way from Churchill to the Alberta Rockies. There, near the headwaters of the Red Deer and Bow Rivers, he met Saukamepee, an elder from the Piikani nation.

Thompson spent the winter with the old man, learning about indigenous people and their ways. In particular, he was impressed with the attention given to even minute changes in the environment, such as trampled grass and broken twigs. It left the young man with a lifelong admiration for native peoples.

Illustration: Wikipedia

Leaves the Hudson’s Bay Company

The Hudson’s Bay Company recognized and promoted him for his surveying accomplishments, but when he was twenty-four, they told him to refocus his attention on fur trading. Frustrated in his ambitions, he abandoned the Hudson’s Bay Company three years later and walked 130km through the snow to join the rival North West Company. It offered greater opportunities for him to continue his surveying work.

Relying chiefly on a small sextant, a powerful telescope, his keen mind and memory, and incredible mapping skills, Thompson spent more than thirty years exploring and mapping from the Peace River in the north to the mouth of the Columbia River in the south and east to include both shores of Lake Superior. Thompson was instrumental in setting the U.S.-Canada border along the 49th parallel.

In addition to documenting geographical features, Thompson recorded information on dozens of cultures he encountered during his travels. His maps and hundreds of journal pages covered nearly four million square kilometers, and he is thought to have covered some 80,000 kilometers on foot, by canoe, on horseback, dogsled, and snowshoes. That’s twice the equivalent of the Earth’s circumference.

Thompson at work taking a noon latitude with his portable sextant. Drawing by Charles William Jefferys/Library and Archives of Canada

Illnesses, marriage

If those accomplishments aren’t enough to impress, consider that after years of squinting through telescopes and surveying equipment, he lost the sight of one eye, nearly died from malaria, was debilitated by cholera, and, thanks to a badly healed broken leg, walked with a limp during many of those years.

Thompson married a thirteen-year-old Metis girl, Charlotte Small when he was twenty-nine. They remained married for fifty-eight years and had thirteen children, including several while he was actively exploring.

In 1812, he moved his family to Montreal. Giving his children an education was high on his list of priorities, but the effects of European settlement on native peoples by disease and alcoholism, unprincipled land seizure, and the erosion of traditional cultures, angered and disheartened him.

Thompson’s field notes from his survey of the Niagara River. Photo: Archives of Ontario

Troubled times for Thompson

Although Thompson is reported to have been steadfast in his faith until the end, he must have felt the Devil exacted a stiff penalty for those losses at checkers. His investments were ill-advised, and he lost most of his money. Two of his children died, another left home in a fit of rebellion, and the brilliant geographer was reduced to working odd jobs.

Finding a publisher for his maps proved difficult, although he finally sold them for a pittance. Arrowsmith, the firm purchasing the maps, didn’t publish them as Thompson’s work but rather used them to update their own maps and charts. At one point, he is said to have sold his surveying equipment and a winter coat to feed his family.

Thompson moved in with a daughter and her husband, turning his attention to his voluminous journals which he hoped to publish. Somewhere along the way, the sight in his remaining eye began to fail, and his journal efforts faltered. Unrecognized by the public for his enormous contributions to North American geography and living in poverty, Thompson died in 1857. His death was a profound loss for Charlotte, and she died a few months later. Thompson is buried in Montreal’s Mount Royal Cemetery.

In much-delayed acknowledgment of Thompson’s contributions, Canada has raised several monuments to him, including one in Jasper National Park in Alberta, another at Rocky Mountain House, also in Alberta, and one in Castlegar, British Columbia, among other locations. The nation has also honored him on several postage stamps. North Dakota’s David Thompson State Historic Site recognizes his work as a geographer and astronomer, particularly in 1797-98 when he mapped much of what is now North Dakota.

Pages from Thompson’s journal. Photo: Archives of Ontario