In the wake of the four recent avalanche deaths on Shishapangma, veteran 8,000m climbers and international mountain guides are demanding changes in how these commercial peaks are climbed. All agree that safety must go before summit rates, and clear, pressure-proof leadership is essential. Otherwise, the tragedies will keep occurring.

On Oct. 7, about 50 commercial climbers and their guides hurried up Shishapangma. The group included several vying to complete all 14 8,000m peaks. Foremost among these were Anna Gutu and Gina Rzucidlo, who were competing with each other to become the first American woman to finish this list. Others, including guides Nirmal Purja and Mingma G, were targeting personal records — in their case, completing all 14 of the world’s highest peaks without supplementary oxygen.

Conditions on Shishapangma were sketchy — cold and windy, with high avalanche risk. Almost all the climbers turned back at 7,600m, but the two rival American women, short-roped to their sherpa guides, pressed on. Each pair died in a separate avalanche.

Post-monsoon avalanches

Ralf Dujmovits of Germany posted on Instagram last week, explaining why Shishapangma’s north side (the normal route) is particularly avalanche-prone in the post-monsoon season. “I don’t raise my voice too often but I am so saddened and shocked about what happened!” he wrote.

In a conversation with ExplorersWeb, Dujmovits, a 14×8,000m summiter, UIAGM guide, and veteran expedition leader, stresses a guide’s responsibility to maintain authority during pressure-packed ascents with ambitious clients.

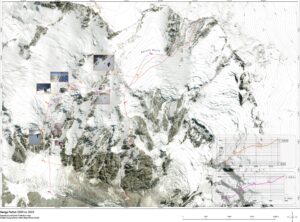

In this graphic, Dujmovits shows how the southerly winds on Shishapangma during the typical high-pressure systems create dangerous snow slabs on the upper part of the north side. The avalanche risk increases in the fall. Photo: Ralf Dujmovits

“The gigantic slope above 7,300m on Shishapangma’s north face is not steep enough to regularly avalanche naturally,” Dujmovits said. “However, when disturbed by the added weight of a climber, or even through the vibrations of approaching climbers, the faceted snow can collapse and begin to slide, along with the hundreds of tons of snow on top of it.

“This is typical in autumn, especially when it is very cold, and there have been several similar accidents like these.”

Previous fatalities

In 2014, he explained, Sebastian Haag and Andrea Zambaldi died in an avalanche on the normal route. In Dujmovits’ opinion, Shishapangma can be climbed in the fall but with caution. You need to stick to the classic route that goes up the summit ridge, across the central summit, and on the knife-sharp snow crest to the main peak.

“You have to avoid the north-facing slope altogether,” he says. “There is no safe route across it. When I climbed from the south side in 2005 with Gerlinde Kaltenbrunner and Hirotaka Takeuchi, we then traversed and descended down the north side. Let me tell you, that descent was much more dangerous than climbing the south side!”

Left to right, Hirotaka Takeuchi and Ralf Dujmovits on the summit of Shishapangma in 2005. Photo: Gerlinde Kaltenbrunner

Ignoring the signals

Italians Mario Vielmo and Sebastiano Valentini said that everyone on the mountain that day knew that the upper section was risky because there had been a large avalanche the previous day. Vielmo and Valentini were in Camp 1 from the afternoon of Oct. 5 to Oct. 7. They saw conditions evolve into a textbook avalanche situation. Fresh snow falling on the south side was blown to the north side, creating dangerous windslabs.

“There was snow falling at altitude from Oct. 4 to Oct. 5,” they explained. “It was warm in Base Camp, so the snow didn’t last, but we estimate that there was about half a meter at Camp 4 and above. On the morning of Oct. 7, it was extremely cold and windy on the upper slopes of the mountain. Wind, fresh snow, and cold…made a recipe for avalanche disaster.”

Close call on Oct. 5

The first big warning sign came on Oct. 5, when climbers heading to Camp 2 triggered a big avalanche. They fell 100m, but luckily no one was badly hurt.

The location of the avalanche on Oct. 5, which buried Sanu Sherpa and Naoko Watanabe. Photo: Mario Vielmo

“[This] was a big alarm sign, and everybody saw it,” the Italians said.

One of the sherpas involved in the slide was two-time 14×8,000m summiter Sanu Sherpa. According to the Italians, he was also a cousin of Tenjen Lama Sherpa, who died two days later.

Sanu was guiding Naoko Watanabe of Japan, who confirmed the events on social media. “Two days before the summit push, Sanu and I were also caught in an avalanche and we were both buried. I couldn’t breathe for about three seconds and luckily my face came out and I was saved,” she said.

But their experience was not enough to dissuade climbers from hastening up the mountain the following day.

The ill-fated summit push

Joint teams from EliteExped and Imagine Nepal rushed up the mountain immediately after reaching Base Camp. As team member Naila Kiani reported, they arrived with their high-altitude gear on their backs, ready to start the climb without wasting a minute.

Gina Rzucidlo had started a little earlier, reached Camp 2 before the newcomers, and waited there. In addition, some climbers outfitted by Seven Summit Treks joined the push, hoping to take advantage of the freshly packed trail.

There were about 50 climbers involved in the summit push and very few ropes. Teams had planned to fix some, but in the end, no one did. As the teams reported, every client was supported by at least one sherpa. When the terrain steepened, they progressed short-roped.

The Italians, climbing without oxygen, were not yet ready to try for the summit. The two of them might have followed the footprints in the snow on a partial acclimatization round but decided against it because of the tough conditions.

Wrong way

“They [the two women and their sherpas] took the wrong routes,” the Italians explained. “They went straight into the most avalanche-prone sections. You could tell it was a race because they both took different routes [instead of collaborating to break trail] at the same time, obviously trying to go faster than the other.”

Rzucidlo took the direct route to the main summit that Nirmal Purja and his sherpa team had climbed during his Project Possible in 2019. At first, Anna Gutu went for the normal, classic route to the ridge and the central summit. But eventually, she stopped for nearly an hour and then changed course and went across the slope, straight up, until the avalanche swallowed them.

Vielmo said it was impossible to know what caused the slide but suggested that the climbers themselves might have set off the slab.

The routes followed and the location of the first (‘prima’) and second (‘seconda’) avalanches on Shishapangma, Oct. 7. Photo: Mario Vielmo

“Perhaps, if they had taken Inaki Ochoa’s variation, they might have found better conditions, since that route goes down a bit from the ridge, crosses the flat upper plateau, and then goes up straight to some rocky sections near the summit, which are safer,” Vielmo ventured. “And yet, they would have needed to check conditions very carefully on that route too.”

Who decided up there?

Neither Gutu nor Rzucidlo had enough knowledge to assess either the conditions or the route. Tagging them as “experienced” after climbing 13 8,000’ers with sherpa guides is misleading. Gutu wanted to emulate Purja’s speed record and complete the “task” as fast as possible. Rzucidlo had started years before, but she had always climbed as a client in fully guided teams. Both women lacked the skills to climb 8,000’ers self-sufficiently.

Sebastiano Valentini and Mario Vielmo in Tibet, before reaching Shishapangma’s Base Camp. Photo: Mario Vielmo/Facebook

Rzucidlo followed Tenjen Lama, who had been on Shishapangma that spring, guiding Kristin Harila.

“We met Gina [Rzucidlo] at dinner when she showed up in Base Camp and she looked quite distracted and absent-minded,” Valentini said. “She was always asking about where her gloves or her glasses were…And she absolutely trusted Tenjen. ‘Lama (Tenjen) can do absolutely everything’, she would say.”

So who decided on the route and how to progress? And who made the call that it was safe enough to go up at all? Who was the leader?

“There was no leader up there,” Valentini said. “The group had a Nepalese Base Camp manager, but I don’t know whether he had any authority over the climbers and their sherpas. In Gina’s case, I guess the leader was Tenjen Lama.”

Tenjen Lama Sherpa. Photo: Tenjen Lama/Instagram

Could Tenjen have stopped the unsafe push?

But did Tenjen Lama have the authority to abort the push? Was he prepared to withstand the pressure from such a driven client?

Several climbers on the mountain were told that someone in Base Camp radioed Tenjen Lama and suggested (or told him) to turn around. We have asked the Base Camp manager but have not yet received an answer.

Meanwhile, Gutu belonged to a team with a clear leader, Nirmal Purja. Whether he was involved in any decisions is something he will have to explain. When the first avalanche struck, both Purja and Mingma G were not affected because they were much lower down. They climbed at a slower pace because both were engaged in their own record pursuits, aiming to complete the 14×8,000’ers without oxygen.

“What happened, happened,” Vielmo says now. “The most important thing is that the tragedy on Shishapangma must be a turning point for all those involved in commercial expeditions to 8,000’ers, in order to prevent similar events in the future.”

He added: “This is especially important among the new generation of clients on commercial expeditions, who go to the mountains with no experience in mountaineering at all, no knowledge about the dangers or mountain conditions, and no way to make the right decisions.”

Who cares about conditions?

Dujmovits and Vielmo agree that fast-climbing 8,000m peaks is a dangerous new trend. “The speed records of Nirmal Purja and Kristine Harila must be considered as two personal experiences to prove something, but they cannot become a new model,” Vielmo said.

Even more dangerous is the apparent lack of caution some expedition leaders treat conditions on the mountain. On Oct. 4, Nirmal Purja showed his leadership on Cho Oyu. During the summit push, the team was caught in a complete whiteout and Mingma G considered turning his team around.

“I still don’t have great energy to take risks,” Mingma G wrote, referring to the trauma he suffered after the death of three of his employees in Everest’s Khumbu Icefall last spring. “But Tejan Gurung and Nimsdai (Nirmal Purja) were from Army backgrounds so they have different mindsets and techniques.”

Mingma G is an accredited UIAGM guide. Purja and Tejan have no such international accreditation as mountain guides but rely on their military training. Back in Base Camp successfully, they met two climbers who had turned around that same day because of whiteout conditions: UIAGM guide Prakash Sherpa and skier Benedikt Boehm. When Boehm told Purja about their experience, Purja replied: “Who cares about the conditions!”

Boehm reflected on the episode back at home in an interview with Austria’s Berwelten magazine. “Purja has commercialized…the myth of achieving the 14×8,000’ers quickly and safely through the 14 Peaks movie,” Boehm wrote. “This has resulted in a sense of invulnerability. What has not changed are the objective hazards of the mountain.”

Read his post here:

Prakash and Boehm, by the way, waited for better conditions and climbed Cho Oyu on Oct. 6-7 in 12 hours and 35 minutes, without oxygen or personal sherpas. During that time, disaster struck on Shishapangma.

A dangerous trend

“It’s all about the conditions,” Dujmovits insists. “As long as we have guides who take conditions so casually, we will have more deaths on the mountains. Clients should evaluate very carefully who they climb with; not necessarily the most famous, but who guides the safest.”

Dujmovits added: “Some may say it was the women’s competition that caused the avalanches, but they wouldn’t have got that far if the guides had been able to handle the pressure. Guides must learn to say no, it is too dangerous. They must learn to turn their clients around. In the end, it is the guide who must make the decisions, no matter how much pressure there is or how much money clients have paid.”

The competition up there, Dujmovits pointed out, was not only among Anna Gutu and Gina Rzucidlo. There was also, as always, competition among the outfitters.

False promise

“The example of Purja has given many potential clients the idea that you can speed up the 14 8,000’ers,” said Dujmovits. “Kristin Harila was inspired by his film and jumped to launch her own record. I was on Manaslu when she summited last year [in her first attempt at a speed record], and she went to the summit in hair-raising conditions. I couldn’t believe anyone would attempt the summit like that. She later admitted they heard avalanches as they climbed. Days later, I was in Camp 3 when an avalanche injured nine Nepalese climbers. I helped in the rescue.”

This is what Harila posted about her Manaslu experience in the fall of 2022:

Finally, Dujmovits noted the importance of transparency and reporting what happened on the mountains, both good and bad.

“If we don’t speak about this, more accidents will happen,” he said. “A guide must be, first of all, honest and communicative with clients about conditions. When accidents happen, the expedition leaders must be very proactive in explaining what happened and why.”