During the violence and instability of 17th-century Europe, monarchies and religions struggled for dominance. Constant conflict drove thousands of refugees to distant lands. Jean Baptiste Tavernier emerged from this instability to pioneer trade in the Far East.

Background

Tavernier hailed from a Protestant family of engravers and geographers based in Paris. He grew up during a time of great upheaval in Europe. Catholicism and Protestantism struggled for dominance, and Tavernier’s family traveled back and forth between France and Belgium, depending on the situation for Protestants in each.

Despite the instability in his youth, Tavernier busied himself learning engraving and cartography. His father’s travel tales enraptured him. Once he was old enough, he worked in royal courts and with the military.

Through his work, he visited England, Italy, Switzerland, Hungary, Germany, and the Netherlands. He also snagged an important position as controller of the household of the Duke of Orleans. But despite his stable occupation, Europe was not enough for him. He longed to explore the East.

A portrait of Jean-Baptist Tavernier. Photo: Nicolas de Largilliere

Tavernier heard that a few men were going to travel to the Levant, and he decided to tag along. On his first trip, he traveled through Constantinople, Anatolia, Armenia, Persia, Iraq, Syria, and Malta.

The King of France requested that Tavernier write about his travels to inspire people to trade in the East and discover new routes. Tavernier went on five further voyages and wrote about them (with the help of a biographer) in The Six Voyages of Jean-Baptiste Tavernier.

In this travelogue, he illuminates court politics, royal family dramas, and common people’s feelings toward their sovereigns. The first volume details the route from Isfahan, Iran to Agra, India.

Tavernier also wrote about customs laws and the transport of precious metals and jewels. For example, in Surat, he says: “As soon as the merchandise is landed at Surat, it has to be taken to the customs house, which adjoins the fort. The officers are very strict and search persons with great care. Private individuals pay as much as four and five percent duty on all their goods.”

Gem dealing

Tavernier’s greatest journey was in 1638. He went to India and spent five years making the right connections with emperors and court officials. At the time, the Kingdom of Golconda was the center of India’s diamond trade. Here, he discovered his vocation as a gem merchant.

He arrived in Golconda in 1642. Golconda’s diamonds came from the Kollur Mine and became world famous. They included the Daria-i-Noor (one of the Iranian Crown Jewels), the Nizam Diamond (which belonged to the Nizam of Hyderabad), the Dresden Green Diamond (which belonged to King Augustus III of Poland), and the Great Mogul Diamond (which belonged to the fifth Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan). However, one particular Golconda gem stood above all others.

In 1666, Tavernier came upon a raw, uncut diamond of 115 carats. It was unlike any gem he had ever seen. The diamond was described as violet-colored. After cutting and other aesthetic touches, it was called the French Blue, and then eventually the Hope Diamond.

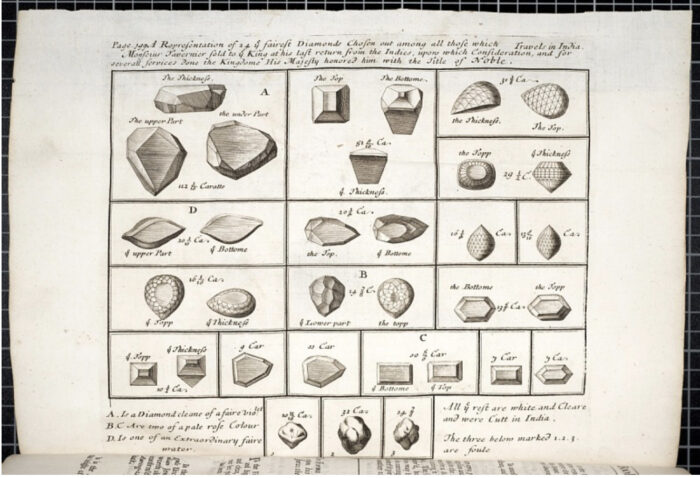

Tavernier’s illustrations of gemstones. Photo: Smithsonian Museum

The Hope Diamond underwent three phases. In its rawest form, it was called the Tavernier Diamond and was 115 carats when extracted from the mine. Then, it was cut to 69 carats and renamed the French Blue Diamond after it was sold to the King of France, Louis XIV. In 1792, someone stole it during the French Revolution. It was cut again, becoming the Hope Diamond. It was now approximately 45 carats.

After vanishing during the French Revolution, it re-emerged in London in 1812. After several private owners, the Smithsonian Museum bought the diamond. Though cut three times, it is still the largest diamond in the world and is worth approximately 350 million dollars.

As a gem merchant, Tavernier formed close relationships with his customers, particularly royalty. He made acquaintances in India, Persia, and Java. Over decades of travel, he earned a reputation as the top gem merchant in Asia.

A cursed diamond?

The Hope Diamond is said to be cursed. The details surrounding Tavernier’s procurement of the diamond are not just fantastical and defamatory but what started the legend. After he obtained the diamond, rumors began circulating in jewel trade circles. One popular tale involved Tavernier murdering someone and stealing the diamond from the head of a sacred statue of Sita, a Hindu goddess who is the consort of the god Rama.

Those who believe in the curse claim that wild animals killed Tavernier. However, historical records don’t support this. We know that he died in Moscow, most likely from natural causes.

But some owners of the Hope Diamond indeed suffered financial ruin, illness, or death. One early example is Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, who were executed during the French Revolution. In 1910, a Greek jewel merchant named Simon Maocharides owned the diamond for a time. He died after driving his car off a cliff.

In the late 1950s, mailman James Todd carried the diamond to the Smithsonian Museum. Todd then suffered an onslaught of bad luck. First, he suffered a car accident that crushed his leg. Then, his wife died. Next, his dog. Finally, his house burned down. It is hard not to see a trend.

Some researchers believe that the diamond was cut several times to disguise its identity and prevent the French government from repossessing it after it was stolen during the French Revolution. So, other pieces of the diamond could be out there. If so, they could be in European crown jewel collections. The Russians claim to have a piece of the diamond among the Russian Crown Jewels. However, experts have not confirmed this.

Other possible “sister” diamonds (cut from the same stone) include the Brunswick Blue. The Brunswick Blue supposedly belonged to Charles II, Duke of Brunswick. According to Lang Antiques, the Brunswick Blue disappeared from public view after the Duke’s estate was auctioned off in 1873.

Legacy

Tavernier was so influential that a diamond’s worth is calculated using Tavernier’s Law. The worth is determined by the carat weight squared, multiplied by the basic price of the stone.

Tavernier has been the subject of films, including The Diamond Queen (1953) and a series of documentaries.

Author Richard Wise published The French Blue, which dealt with the events leading up to the diamond’s final incarnation as the Hope Diamond. The beauty of the Hope Diamond also inspired the Heart of the Ocean necklace from the film Titanic. However, the Hope Diamond isn’t a brilliant blue sapphire but rather a greyish blue.