It’s a bridge too far to paint Jacopo Larcher as a revisionist. But in European rock climbing, he’s trying to synthesize a future that diverges from its past — and he’s not afraid to confront history in order to do it.

Ask yourself: Would you forgo a bombproof bolt for a marginal cam placement if you were facing a nasty fall?

View this post on Instagram

That’s the game Larcher plays all the time as he barnstorms around his home continent, ignoring bolts on sport climbs. He accepts the hazard as part of an effort to reframe the role of the expansion bolt — the central piece of hardware in a modern route developer’s toolkit.

Making ‘the sharp end’ even sharper

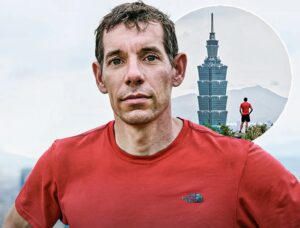

Larcher is The Traditionalist, in his new role for The North Face as well as in practice. Since the mid-2010s, he’s blazed his own trail through the climbing world by creating specific, hard climbs that would terrify most people.

Lead climbers attempting the menacing crux on 2021’s Shikantaza must rely on thin aid climbing gear, placed behind a flake that threatens to rip off, tensioned to cams below to stay in place. Nobody knows how hard Shikantaza is because Larcher never gave it a definitive grade — and nobody else has tried it.

In keeping with the ethics of The Traditionalist, the route could very well stay that way for good. Larcher refused to bolt it partly in deference to its original developer, who tragically died in unrelated circumstances in 2017. And partly because he’s decreasingly interested in the sport climbing game.

Shikantaza is a king line on a spectacular boulder in an idyllic Italian valley — how many souls would siege it if Larcher defanged it with a hammer drill?

To be clear, bolting has advanced rock climbing as a sport more than any other single factor. Most of the world’s hardest routes are impractical to protect with traditional gear, and many are impossible to protect traditionally.

Some are just extremely marginal. Those are the ones where Larcher makes his living.

Watch him jam a skyhook into a tiny horizontal seam on Jeune Et Con, then pound on it with his fist to secure it. Realize, along the way, that it’s the only piece of protection on the whole rig.

A little contrived?

Elsewhere, things get a little contrived. But when they do, it’s important to remember that all climbing is fairly contrived.

Into the Sun is Larcher’s extension of a high-ball boulder problem by Fred Nicole. To begin, the climber stands on bouldering pads with a harness on and starts up. The boulder problem ends at a big hole at about three-quarters height. At this point, the climber usually lets go, falling to the pads below. Instead, a helper hands the climber a pre-rigged rope and trad gear on the end of a pole.

The climber grabs the gear and clips into the rope, the helper becomes a belayer, and the climber tops out on the boulder after another three vertical meters.

Handing up the tools on ‘Into the Sun.’ Contrived? Awkward? Or just sensible? Photo: Screenshot

It’s a little silly. Until you consider that Seb Bouin, Adam Ondra, and the rest of the mutants in the Flatanger Cave often switch between ropes mid-climb. Or that Alex Honnold, on the first ascent of the 15-meter high-ball boulder Too Big to Flail, amassed 36 crash pads at the base. Or that high-altitude climbers are locked in an ongoing mud fight over whether it’s fair to use supplemental oxygen — in an industry that relies on it at least 90% of the time.

Faster, lighter?

Above the noise, though, there’s one mountain perspective from which Larcher’s traditional fixation makes perfect sense. The seemingly invincible “fast and light” ethic supports it all the way.

Bolting a first ascent is heavy, gnarly, expensive work. Plugging a little gear, rappelling down, and walking away like nothing ever happened? Comparatively, it’s light as a feather. If a first ascensionist can get away with it, why face the burden of drilling a bolt at all?

Of course, “getting away with it” is relative. Fear and risk tolerances vary.

Will legions of sport climbers hang up their quickdraws in Larcher’s image? Pile their online shopping carts high with loads of arcane trad and aid equipment like beaks, skyhooks, and ballnuts? Play with sketchy gear placements and evaluate what climbing and, by extension, life is really about?

Would you whip? Photo: Screenshot

I doubt it. It’s too easy (and fun) to show up to a cliff someone already bolted and start playing around on it — trust me.

But Larcher’s not trying to change the past, he’s trying to influence the future. Hard trad climbing, he points out, is a “young movement” in Europe.

“You can really see that other climbers who don’t trad climb start to realize there is this other discipline,” Larcher says in the film. “[Trad climbing] never gets boring. You have to deal with your fears. You have to sometimes decide if you want to go for it, knowing there might be consequences.

“For me, It makes me feel more alive.”

Seems like word’s getting around.