Petroglyphs are hard puzzles to decipher. Despite a wealth of knowledge, historians and archaeologists can’t always put the whole picture together. The mysterious Dighton Rock is a classic example.

Weird inscriptions

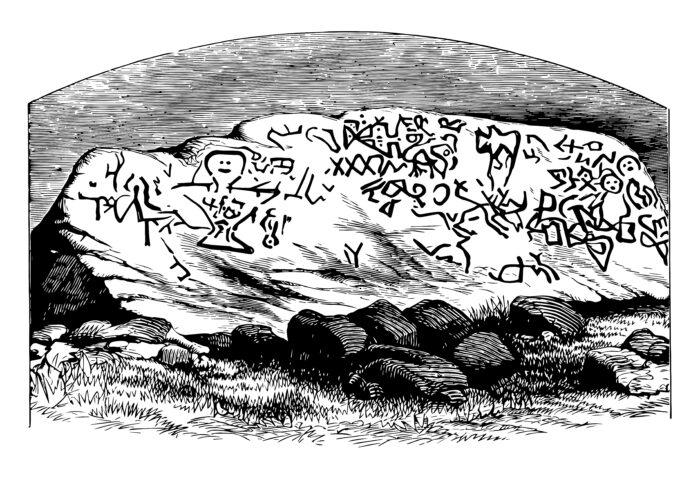

Reverend John Danforth discovered Dighton Rock in 1680. For roughly 20 hours each day, the rock was hidden by the tides of the Taunton River in Massachusetts. The rock weighs 40 tons, is 10 to 11 feet long, and is five feet high. Its greyish-brown sandstone is carved with weird inscriptions, whose origins and meanings continue to elude explanation. Some are intelligible: triangles, infinity symbols, human figures, and animals. The rest look like random scribbles.

To preserve the rock, it was moved in 1963. It now resides in a small museum called the Dighton Rock Museum.

Danforth believed the rock had Native American origins. He speculated that the Wampanoag, Narragansett, or Algonquian peoples might have carved the petroglyphs — most likely, the Wampanoag, he concluded. He thought that the etchings depicted a great battle and a shipwreck.

Danforth sketched the rock, and his drawings are on display in the British Museum.

Dighton Rock inscriptions. Photo: Morphart Creation/Shutterstock

Ten years after Danforth’s discovery, a famous Puritan reverend named Cotton Mather came across it.

“Among the other curiosities of New England, one is…a mighty rock…there are very deeply engraved [drawings], no man alive knows how or when,” Mather wrote in his book The Wonderful Works of God Commemorated. He believed the symbols were Satanic.

Native Americans?

Native American petroglyphs turn up all over New England. Common motifs include geometric patterns, human figures, animals, astronomical features like the sun and moon, and abstract symbols that likely held symbolic significance for hunting rituals, cosmology, tribal histories, and spiritual beliefs. Petroglyphs are also a form of communication, storytelling, and ceremonial expression. They convey important messages about the natural world, ancestral connections, and the spiritual realm. Some people interpret the Dighton Rock petroglyphs as a hunting scene.

Dighton Rock drew enough attention that even George Washington took an interest. He had experience with Native American petroglyphs and agreed with Danforth.

Phoenicians?

Theologian Ezra Stiles, one of the founders of Brown University, extensively researched Native American history and culture in the 1760s. In particular, he focused on the New England area. He visited the petroglyphs and landed on a rather controversial theory. Stiles believed the Phoenicians were responsible.

“I take [the petroglyphs] to be in Phoenician letters and 3,000 years old,” Stiles wrote. “Or Punic or Carthaginian characters.”

He mentioned his hypothesis in lectures and sermons. For example: “…not to mention the visit of still greater antiquity by the Phoenicians, who charged the Dighton Rock and other rocks in Narragansett Bay with Punic inscriptions.”

An ancient Phoenician artifact. Photo: Shutterstock

Historian Cora E. Lutz states that many academics considered Stiles “the American authority on Dighton Rock.”

Despite his expertise in Native American petroglyphs, Stiles’s Phoenician theory is way out there. It touches on the cross-cultural contact theory, whose supporters argue that the Phoenicians influenced American civilizations. But there is no hard evidence for this, merely conjecture. Just because some drawings resemble Phoenician characters does not make them Phoenician without further evidence.

Norse?

Reconstruction of the Viking village at L’Anse aux Meadows, Newfoundland. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

Some people believe that the etchings resemble Viking runes.

In the 1830s, Danish historian Carl Christian Rafn thought he could link the petroglyphs with Viking sagas. Today, historians agree that the Vikings settled briefly in Canada, specifically at L’Anse aux Meadows in Newfoundland. Could Dighton Rock show Viking settlement much further south?

Rafn’s Viking theory was never substantiated.

The Vikings traveled to North America, but did they go south? Photo: Shutterstock

Portuguese?

In the 1920s, Edmund Delabarre of Brown University suggested that the seafaring Portuguese might have carved the rock.

In the early 1500s, Portuguese explorer Miguel Corte-Real explored the Newfoundland coast and vanished without a trace. Delabarre thought that Corte-Real got as far as Massachusetts. Delabarre argues that the glyphs spell out a message: “I, Miguel Cortereal, 1511. In this place, by the will of God, I became a chief of the Indians.”

He also claims to see Corte-Real’s coat of arms on the rock. He dates the glyphs to the 1500s.

Chinese?

Some other wild theories include Chinese or Japanese script. A former submarine lieutenant commander named Gavin Menzies has championed the China theory. He wrote books investigating Chinese exploration of the Americas and proposed that explorer Zheng He discovered America before Columbus.

There is no evidence to support Menzies’s theory, and academics regard his work as pseudohistory.

Verification problems

Why can’t we determine when the Dighton Rock inscriptions were made? Unfortunately, weathering of the rock’s surface has affected the quality of samples. Additionally, because petroglyphs are carved into the rock, they collect mineral crusts. This prevents scientists from extracting accurate samples.

Radiocarbon dating is also impossible. It requires organic material like charcoal, plant material, bone, or fossils to determine age. Petroglyphs carved into rock don’t usually contain organic material.

It is also possible that the carvings are a hoax or the work of bored locals sometime before Danforth discovered the rock in 1680.

Conclusion

Most scholars lean toward Native American origins. If Norse explorers or another foreign group created the petroglyphs, it would challenge the conventional narrative of European discovery and settlement in the Americas, already a controversial debate in academia. For now, without a means of verifying the date of the petroglyphs, we are still only able to guess their origins.