The 13th century was eventful for the people of Medieval Russia. The Kievan Rus had fractured into warring kingdoms, each perpetually rocked by border disputes and revolts. The Mongol army invaded, burning and sacking cities like Kiev and Ryazan, and overturning the old order.

Famine struck in 1215, then again in the 1230s. The desperate people resorted to eating bark and leaves, then cats and dogs, and finally the corpses of the starved. Years of devastating famine led to a revolt against the ruling prince of Novgorod.

Noticing that their neighbors were distracted by their famine and the new “Mongol Yoke,” the Swedes invaded, attempting to carve off chunks of Novgorod. A few years after that, Prussian Catholics invaded as part of the Northern Crusades.

But with all the upheaval, the people of Novgorod still went about their daily lives. They traded goods, collected debts, married and debated politics. Bored children still doodled in the margins of their schoolwork.

Illustrations of the devastating sieges of Russian cities by the Golden Horde. Left, Siege of Kiev, and right, Siege of Kozelsk. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Onfim of Novgorod

Literacy rates were high in medieval Novgorod, and even children of relatively modest background learned and practiced their alphabet. They used birch bark, a readily available material used for cheap, disposable writing.

It is from these scraps of birch bark, uncovered by archaeologists, that we meet Onfim. Living in 13th-century Novgorod, Onfim was about seven years old when he made the art he’s known for today. His drawings are interspersed with writing lessons and feature the charmingly crude imaginings of a young boy bored in class.

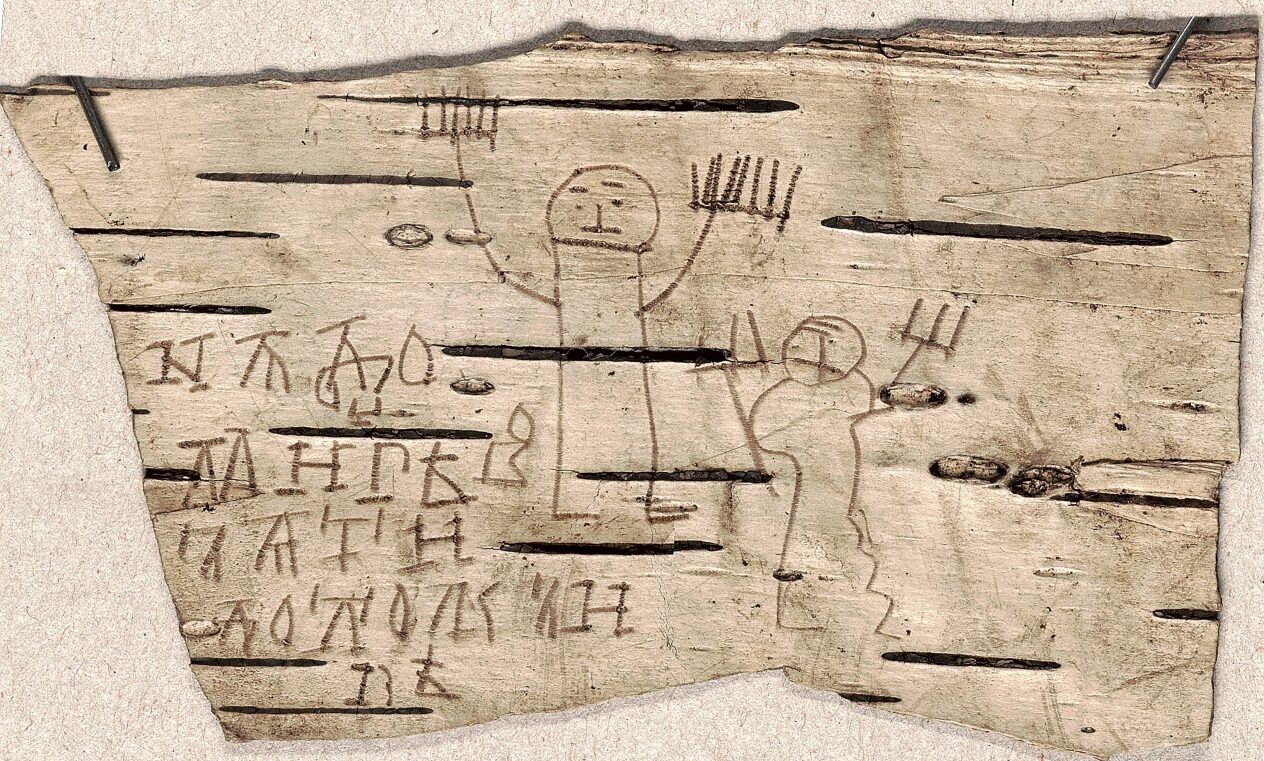

In one example, out of more than a dozen, Onfim begins writing the alphabet, getting about eleven letters in. Then he gives up and draws himself as a mounted knight defeating an enemy. He signs (or perhaps labels) the drawing with his name.

Onfim’s alphabet practice and drawing on birchbark. Photo: Birch Literature Fund/фонда берестяных грамот

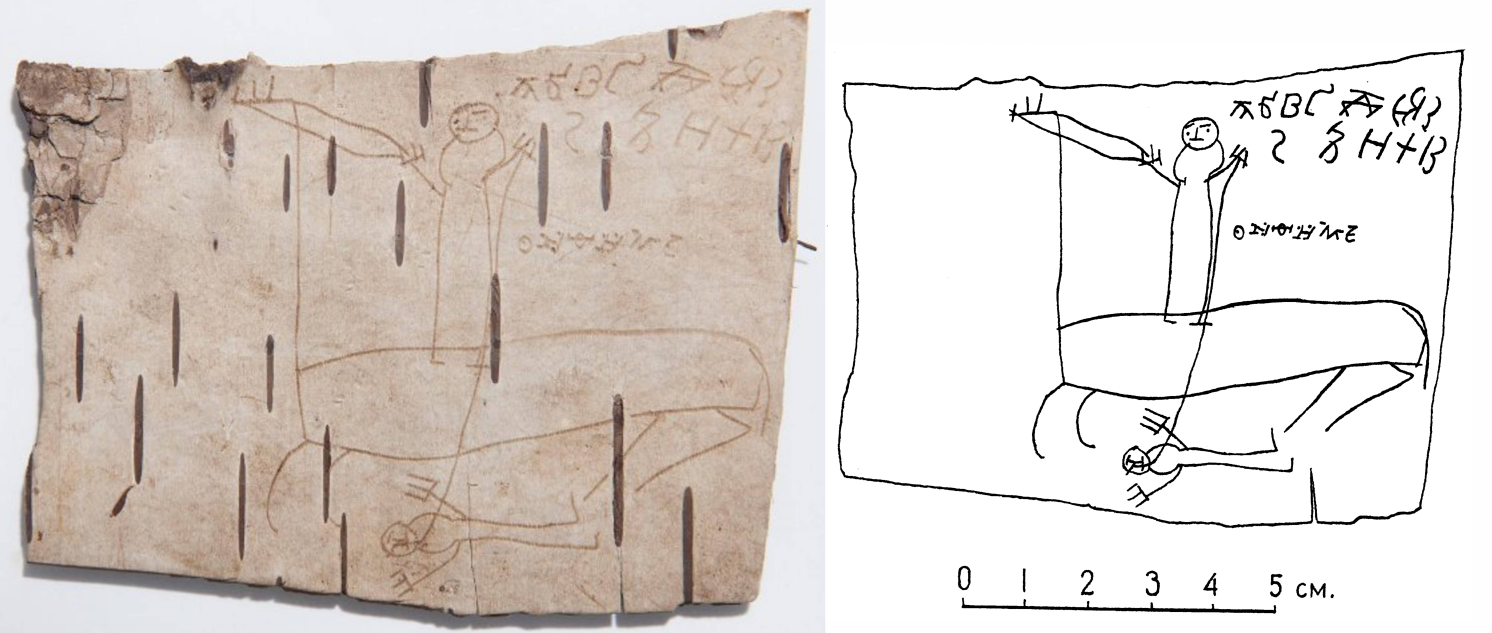

On another birchbark scrap, Onfim draws some sort of wild beast. Helpfully, he labels it, “I am a wild beast.” The beast is passing on good wishes from Onfim to Danilo. Danilo may have been a friend or perhaps even a classmate.

This drawing appears on the back of a syllable writing exercise. Photo: Birch Literature Fund/фонда берестяных грамот

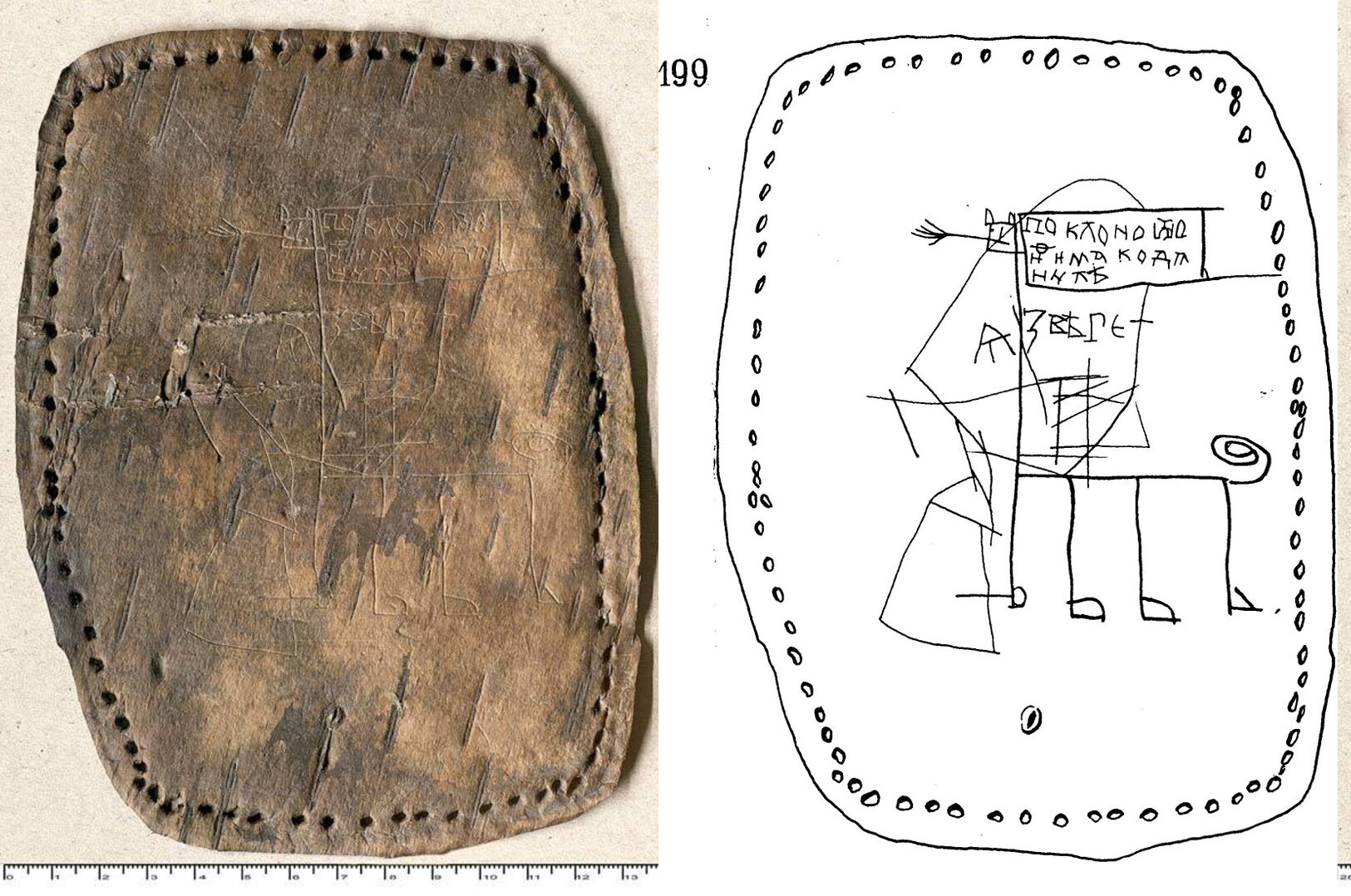

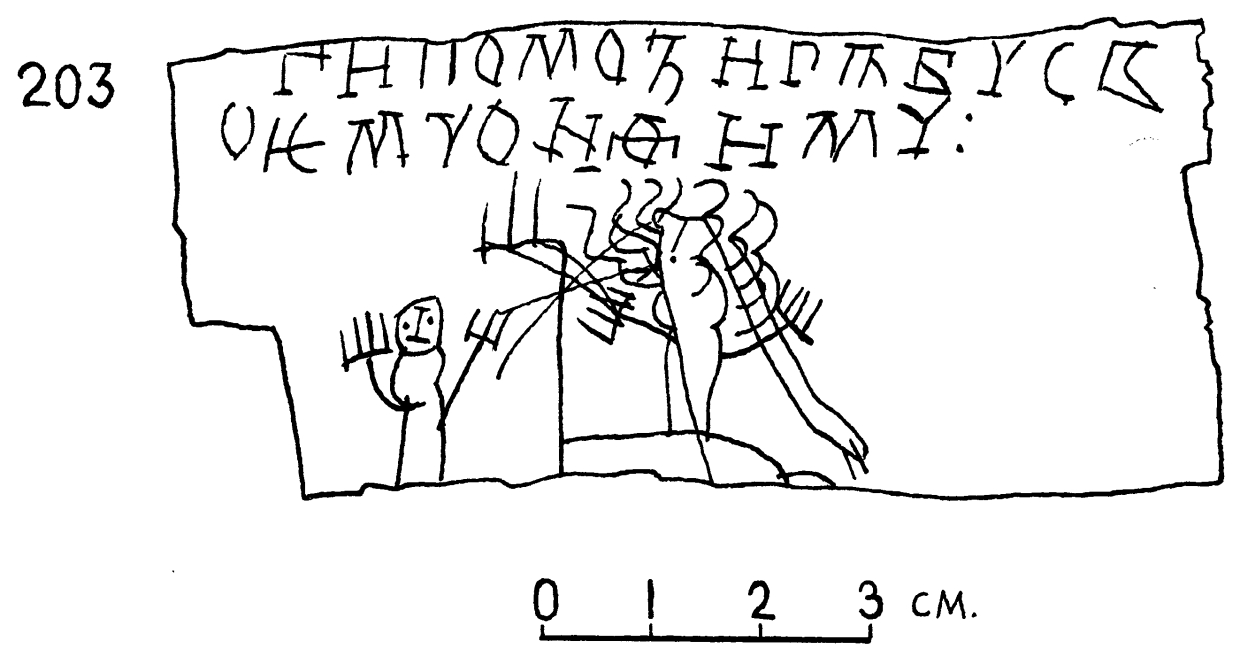

Onfim seems to have liked drawing small figures, not dissimilar from the typical stick figures that children draw today. The writing is usually snippets of prayers or business notes, likely copied from a model.

The text, a prayer, reads, ‘Lord help your slave, Onfim.’ The drawing shows a human figure, left. I have no idea what the right-hand side is supposed to depict. Photo: Birch Literature Fund/фонда берестяных грамот

One man’s trash

Birchbark writing scraps weren’t intended to be kept. They were written, read, and then discarded. There, in the mud, they were accidentally preserved while the streets of Novgorod rose above them. It wasn’t until 1951 that the first birchbark manuscript was rediscovered.

Novgorod was founded sometime around the 9th century, and existed at the crossroads of several trade routes and cultural groups. This, in combination with the anaerobic soil which preserves materials, has led to extensive archeological work in the area.

Discarded birchbark notes are some of the most common discoveries. Over a thousand of them have been found so far. Birch forests ringed Novgorod, and their plentiful bark was harvested for writing. The people of Medieval Russia boiled the bark to soften it, then scraped and cut it to shape. Once they were done with the scraps, they could even use them in the privy.

Most of the birchbark manuscripts are online and can be browsed freely, though many have not been translated into English.

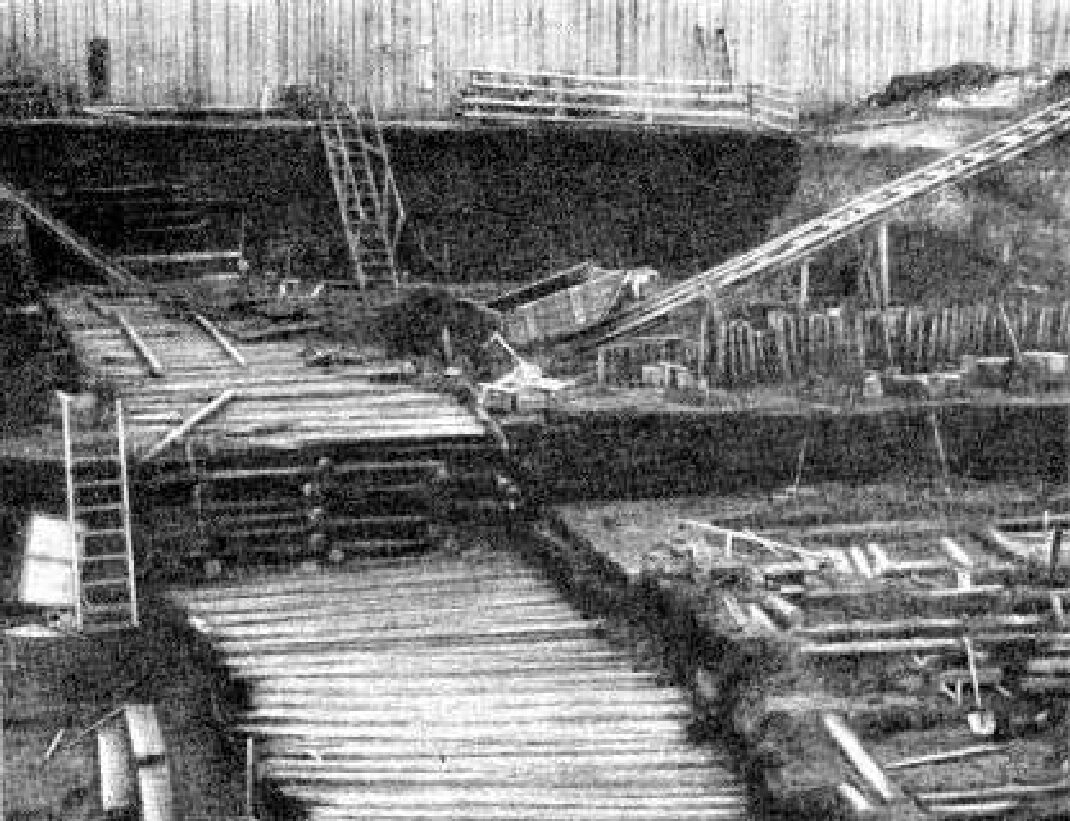

Wooden boardwalks built in the 1120s were excavated in the early 1950s, when the first birch bark manuscripts were found. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

A glimpse of life in Medieval Russia

Most of the birchbark manuscripts are fairly boring — financial transactions, debt records, legal documents. But others provide fascinating and often delightful insights into the people of medieval Novgorod.

One letter was from an older couple to a matchmaker, accepting the woman the matchmaker had proposed as a bride for their son. Another more direct marriage proposal reads: “From Mikita to Malaniya. Marry me -– I want you and you want me…”

Others are informal reference materials, such as a dictionary translating some Balto-Finnic words into Russian. One pair of documents turned out to fit together as one letter, which reported the murder of a man named Zhiznobud, who was killed for his inheritance.

Historians have used the letters to analyze trade networks, economic development, and linguistic change. They also show the high literacy rates in Old Novgorod, which included women as well as men. The informal language provides insights into Medieval Russian slang and obscenities.

But even with all of those insights and curiosities, Onfim’s doodles are by far the most famous. He is a beloved local figure who even has a commemorative statue on the site where the first birchbark letters were found.

The memorial to Onfim shows him writing on birch bark using a sharp pointed tool. Photo: Shutterstock

It can be easy to forget that historical figures, whose lives and societies were so different from ours, were people just like us. The charming, whimsical doodles of a young, bored boy are a reminder of what we have in common. I recommend printing one of his drawings out and putting it up on your fridge.