At 8,125m, Nanga Parbat in Pakistan’s Gilgit-Baltistan is the world’s ninth-highest mountain, and it is dangerous. It earned its “Killer Mountain” nickname because of the high fatality rate during its early climbing history.

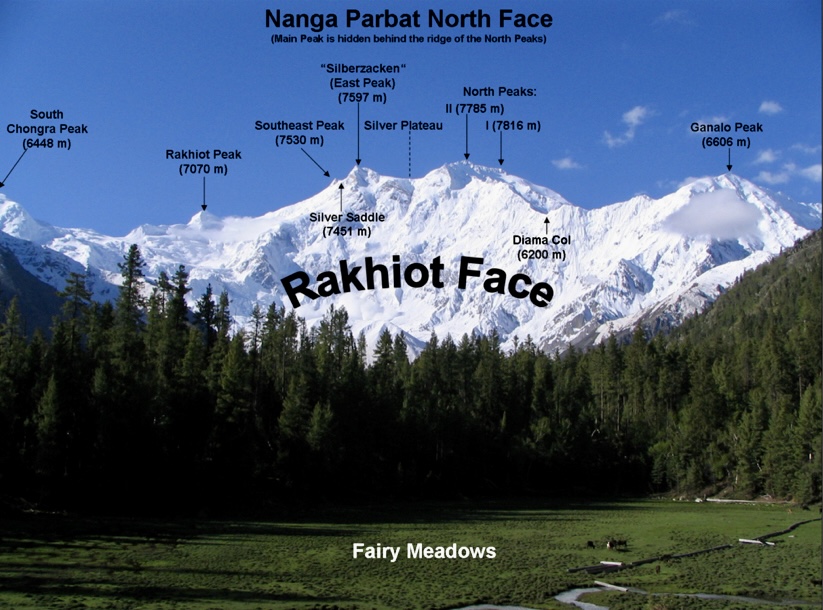

It has three main faces: the south-facing Rupal Face, the northeast-facing Rakhiot Face, and the northwest-facing Diamir Face. The Rakhiot Face is less frequently climbed than either the Diamir or Rupal Faces.

Only three teams have successfully ascended the Rakhiot Face, but more than 30 climbers have died.

The first fatalities

In 1895, Albert Mummery, Ragobir Thapa, and Goman Singh died while scouting the Rakhiot Face. They’re presumed to have died in an avalanche or fall, as their bodies were never found.

Nanga Parbat. Photo: David Goettler

German expeditions

The Rakhiot Face became a focal point in the 1930s, particularly for German climbers, as Nanga Parbat was one of the few 8,000’ers accessible to non-British expeditions because of restrictions on Everest and the remoteness of K2.

The face, characterized by the Rakhiot Glacier, Rakhiot Peak (7,070m), the Silver Saddle (7,400m), and a long ridge to the summit, presented a viable but hazardous route due to its length and exposure to avalanches and storms. The expeditions of this era targeted what would later be known as the Buhl Route, which contributed both to the mountain’s allure and its deadly reputation.

1932: Willy Merkl’s German-American expedition

The first significant attempt on the Rakhiot Face was in 1932, led by German climber Willy Merkl. The expedition, sometimes called German-American because of the inclusion of American climbers Rand Herron and Fritz Wiessner (Wiessner was German-born but became a U.S. citizen), aimed to establish a route via the Rakhiot Glacier and Rakhiot Peak.

Merkl’s party took a route to the left of the Northeast Ridge, which involved steep ice and rock. But they lacked Himalayan experience, and poor planning hampered their progress. They did not have enough porters, and bad weather added to their problems.

Peter Aschenbrenner and Herbert Kunigk reached 7,070m Rakhiot Peak but could not progress further. However, the expedition confirmed the feasibility of a route via Rakhiot Peak and the main ridge.

Willy Merkl in 1934. Photo: Wikipedia

1934: Merkl’s second attempt

Merkl returned in 1934 with a better-prepared expedition, funded by the Nazi government. They targeted the same Rakhiot Face route as in 1932, with a minor variation.

Early in the expedition, climber Alfred Drexel died, likely from high-altitude pulmonary edema. Things only deteriorated from there.

Fierce storms caused chaos on the mountain. On July 6, Peter Aschenbrenner and Erwin Schneider reached 7,895m, one of the highest points ever attained at the time, but worsening weather forced them back.

On July 7, a ferocious storm trapped 14 team members at 7,480m near Camp 4, below Rakhiot Peak. This led to the deaths of Merkl, Willo Welzenbach, Uli Wieland, and six porters: Pintso Norbu, Nima Norbu, Dorje Sherpa, Tashi Sherpa, Dakshi Sherpa, and Gaylay Sherpa. The 1938 Nanga Parbat expedition found their bodies.

At the time, it was the deadliest mountaineering disaster in history. This tragedy, alongside later disasters, cemented Nanga Parbat’s Killer Mountain reputation.

The Rakhiot Face of Nanga Parbat. Photo: Atif Gulzar

1937: Karl Wien’s avalanche disaster

In 1937, another German expedition targeted the same route.

Led by Karl Wien, the team made slow progress because of heavy snowfall. On the night of June 14, a huge avalanche from the hanging glacier on Rakhiot Peak hit them in Camp 4. The avalanche rushed 1,200m across the flat terrace where their camp was set up, burying the tents under meters of ice and packed snow. The campsite was considered safe previously, but a sudden change in weather likely triggered the avalanche.

The avalanche killed seven German climbers (Wien, Hans Hartmann, Adolf Goettner, Martin Pfeffer, Gunther Hepp, Peter Mullritter, and Otto Fankhauser) and nine support staff members (Pasang P., Nim Tsering, Mambahadur, Kami, Gyaljen Monjo, Jigmay, Chong Karma, Ang Tsering II, and Da Thondup).

A search team led by Paul Bauer later found the tents buried under ice and snow, with one climber’s diary noting the camp’s unsafe position. Five bodies were found buried nearby. Described as having “no parallel in climbing annals” for its prolonged suffering, this disaster added to the Rakhiot Face’s deadly reputation.

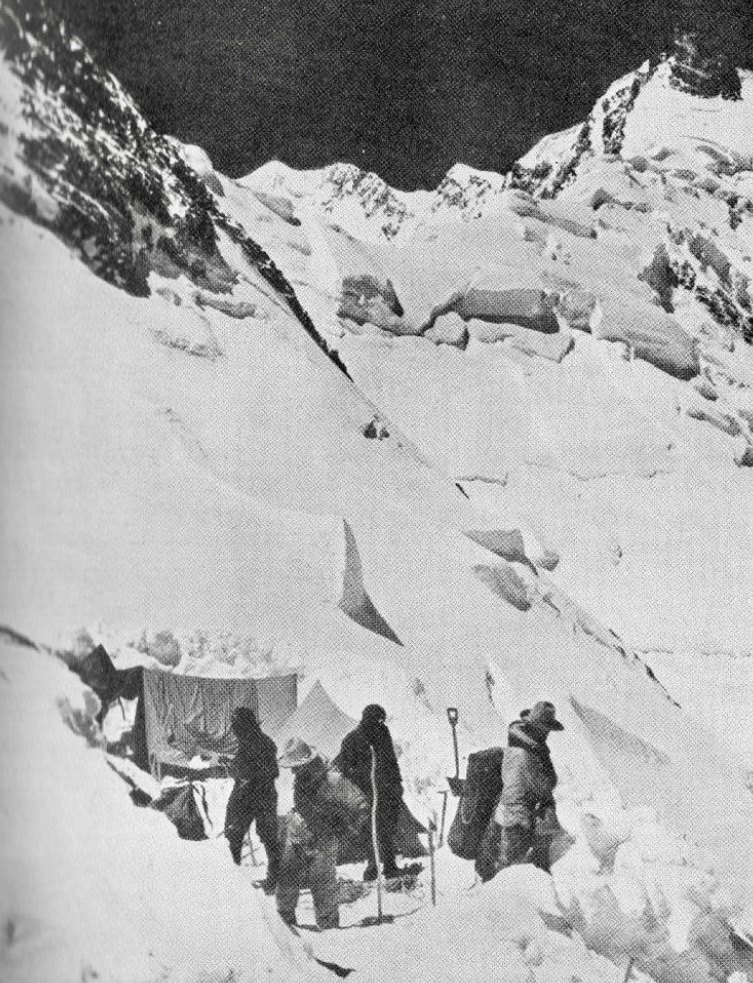

Camp 5 on June 22, 1938. Photo: Himalayan Club

1938: Paul Bauer’s cautious attempt

Paul Bauer led a German expedition in 1938, mindful of the 1934 and 1937 tragedies.

The team reached the Silver Saddle, halfway between Rakhiot Peak and the summit, but bad weather forced a retreat. Heinrich Harrer, a member of the expedition, noted the face’s challenging conditions. No fatalities occurred, but the expedition made no significant progress beyond previous attempts.

1939: Harrer’s reconnaissance

In 1939, Harrer joined a German expedition led by Peter Aufschnaiter, primarily to scout the Diamir Face. However, they also examined the Rakhiot Face, concluding that it was a viable but dangerous route. World War II and their internment in British India halted further attempts.

The 1930s saw five German expeditions to the Rakhiot Face, with at least 25 deaths and no successful ascents, underscoring its lethality.

The traverse of Rakhiot Peak, between Camps 5 and 6, on July 22, 1938. Photo: Paul Bauer

1950: the British winter reconnaissance

The first documented winter attempt on Nanga Parbat occurred in December 1950, when a three-member British team of William Crace, John Thornley, and Robert Marsh scouted the Rakhiot Face.

Marsh descended with frostbiten toes, leaving Crace and Thornley in a tent at 5,500m. Both disappeared, likely swept away by an avalanche or caught in a storm.

“Thornley and Crace were both extremely determined,” Marsh wrote for the Himalayan Club. “Thornley, for instance, marched 265km to Nanga Parbat over the Babusarr Pass, wearing a pair of gym shoes, in six days, and was in no way fatigued at the end. They were a fine pair of friends, and it took an expedition of this sort, where we lived close, in difficult conditions, to bring out fully the great qualities of endurance, patience, and kindness which were so characteristic of them. I am sure they wish for no better tribute than that. When they were last seen, they were still going up and still going strong.”

1953: Nanga Parbat’s first ascent

The first successful ascent of Nanga Parbat was in 1953 via the Rakhiot Face. The German-Austrian expedition was led by Karl Maria Herrligkoffer (who did not climb), whose half-brother Willy Merkl had died in 1934.

The team included Austrians Hermann Buhl, Peter Aschenbrenner, Walter Frauenberger, and Kuno Rainer, plus Germans Otto Kempter, Hermann Kollensperger, Albert Bitterling, Fritz Aumann, and Hans Ertl. It also included several (unnamed in the literature) local porters who carried supplies to Base Camp and up to Camp 4.

The expedition followed what became the Buhl Route: starting at the Rakhiot Glacier with Base Camp at 3,967m, ascending to Rakhiot Peak, traversing the Silver Saddle, and climbing the North Ridge to the summit.

On May 24, the expedition reached Base Camp. On June 10, Buhl, Kollensperger, and porters set up Camp 2 at 6,200m on the Rakhiot Glacier. Two weeks later, the climbers and porters established Camp 4 at 6,700m, below Rakhiot Peak.

On July 1, Buhl, Kempter, Frauenberger, and Ertl set up Camp 5 at about 6,950m with porter support. The porters then returned to the lower camps.

The Rakhiot Face. Photo: Muhammad Arif Baltistani

Hermann Buhl’s solo summit push

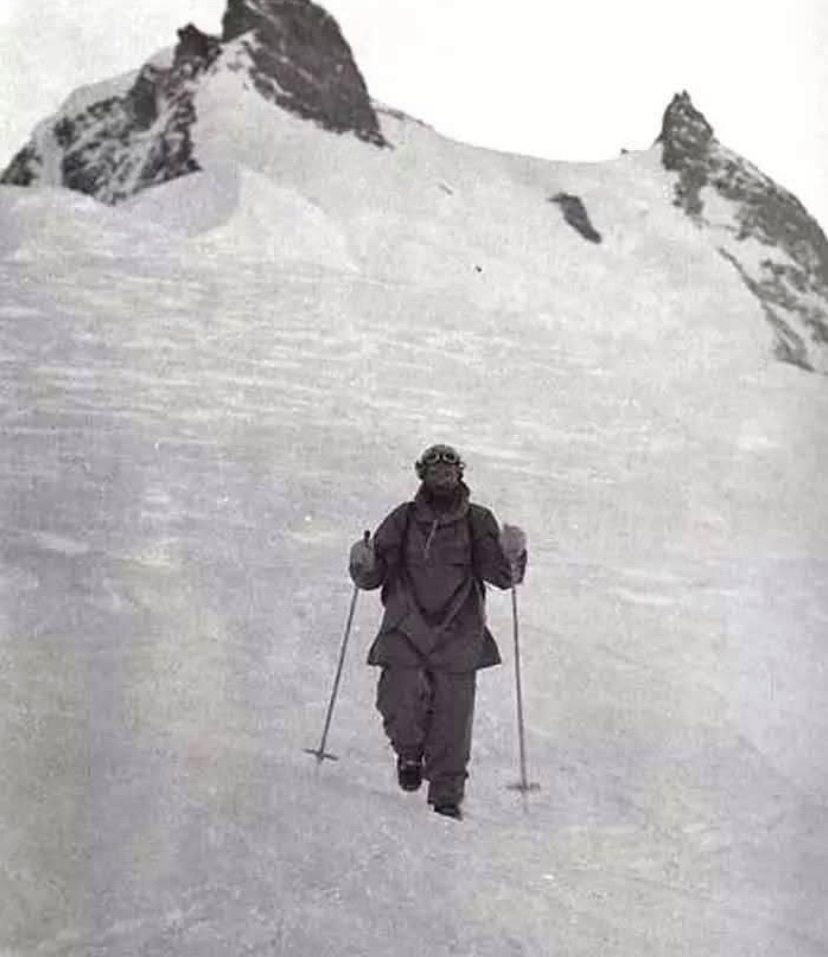

On July 2, Buhl and Kempter stayed at Camp 5 before Kempter turned back. After delays and disagreements, Aschenbrenner, the climbing leader of the expedition, ordered a retreat because of the approaching monsoon. Buhl, determined to summit, continued alone.

On July 3 at 2 am, Buhl started his summit push, carrying food, a flag, some pervitin and padutin pills, but no rope and no supplemental oxygen. His solo push was in alpine style.

Pervitin was a drug containing methamphetamine, a powerful stimulant. It was widely used by the German military during World War II to enhance alertness and relieve combat fatigue. Padutin improves blood circulation and prevents frostbite by dilating blood vessels. Yet despite the pills, Buhl did suffer frostbite.

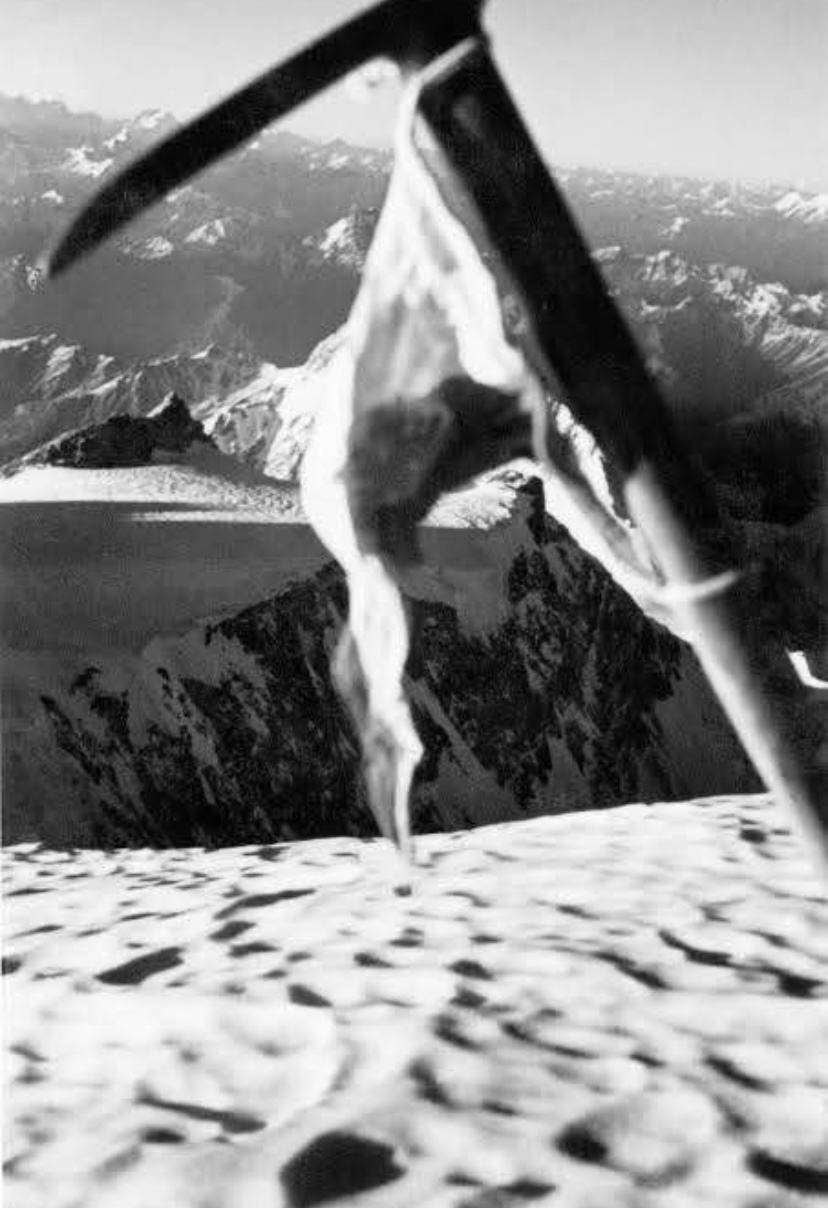

Hermann Buhl’s summit photo. Photo: Hermann Buhl

By morning, Buhl reached the Silver Saddle at 7,450m. On July 3, by 2 pm, he hit the Bazhin Gap at 7,830m, dropped his backpack, and climbed the Shoulder (8,070m). After a tough rock section, he reached Nanga Parbat’s summit at 7 pm the same day, after a grueling 17-hour climb. He left his ice axe on the summit.

On the way down, he bivouacked overnight on a narrow ledge at 7,900m. He returned to high camp on July 4 and reached Camp 5 at 7 pm after 41 hours, exhausted and frostbitten.

Buhl’s solo push was a monumental achievement and is detailed in his book Nanga Parbat Pilgrimage.

Only four years later, Buhl disappeared on 7,665m Chogolisa.

Hermann Buhl descending. Photo: Hans Ertl

Later ascents

The second ascent of the Buhl Route came on July 11, 1971, when Slovaks Ivan Fiala and Michael Orolin made the second ascent of Nanga Parbat’s Rakhiot Face. Other members of the same expedition achieved first ascents of the southeast peak (7,600m) and the foresummit (7,850m).

The climbers had also attempted the Buhl Route in 1969. That time, adverse weather and logistical challenges halted them before the summit. They reached 6,950m.

This 1971 expedition remains the only successful repetition of the Buhl Route.

The Japanese Route

In the summer of 1995, Japanese climbers Hiroshi Sakai, Yukio Yabe, and Takeshi Akiyama established a new route on the Rakhiot Face, ascending below the East Peak and traversing to the North Ridge near the North Peak.

“After a 1992 reconnaissance to the north and a subsequent study of aerial photos, I was convinced we could climb a new route via the ridge derived from the East Peak of Silver Crag,” Sakai wrote in the American Alpine Journal.

The Japanese party consisted of 10 members, though only three members had adequate experience at high altitude. Of these three, two were soon injured and unable to climb.

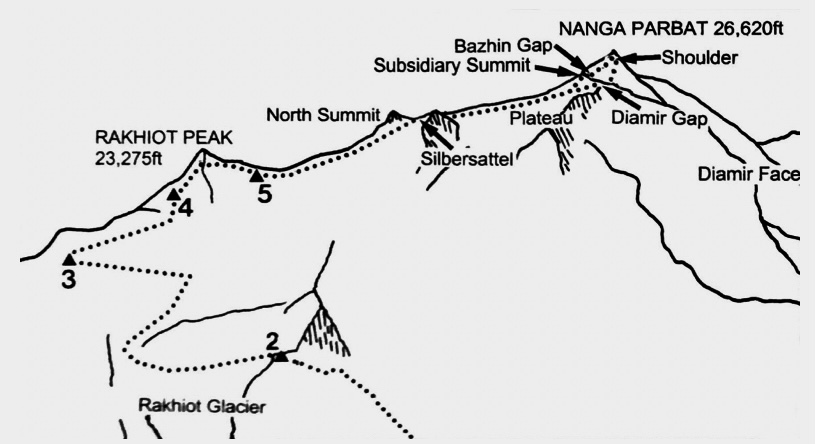

A sketch map of Nanga Parbat. Photo: Himalayan Club

The expedition began on June 5 with a three-day march from Tatoo to a temporary Base Camp at 3,900m, using 100 porters to carry three tons of supplies. The main Base Camp was at 4,500m on the Great Moraine, higher than typical due to the long summit route. Acclimatization took five days, and they had established Camp 1 at 5,300m on the Rakhiot Glacier by June 11. From here, they deviated from the 1953 route.

The route from Camp 1 to Camp 2 involved a steep wall of snow and granite reaching 5,700m. The climbers faced a grade IV+ rock crack and a hazardous snow gully prone to rockfall named the Confessional Pitch because of its danger. On June 26, a falling stone injured one climber’s arm, and he had to withdraw.

“As we climbed higher, we felt more and more rockfall flying down toward us, as our route led toward the upper part of this snow gully,” Sakai recalled.

Inching higher, another injury

After overcoming an overhang and a jagged snow ridge, they set Camp 2 at 5,900m on June 25. Above Camp 2, at 6,300m, a 300m ice tower posed a major obstacle. The team navigated a vertical slit in the ice, climbing four pitches at 70°. Beyond this, the route eased into knee-deep snow along a ridge, leading to Camp 3 at 6,700m, established on July 4.

On July 7, Tamura was injured by a falling stone at the Confessional Pitch, requiring a three-day rescue. With only six climbers left, the team abandoned plans to traverse Nanga Parbat and rested until July 12.

The route to Camp 4 traversed the Silver Saddle’s flanks, tackling Yabe’s Crack, a 50m grade V climb. By July 18, after navigating 800m of snow and rock, Camp 4 was set at 7,350m near the Silver Plateau.

The Rakhiot Face. Photo: 8000ers.com

The summit push

On July 22, Sakai, Yabe, and Akiyama left high camp toward the summit. However, soon after, they returned to Camp 4 because Akiyama felt pain in his chest, and Yabe’s fingers and toes had gone numb with cold. During that night, they took oxygen to regain their strength.

On July 23, Sakai, Yabe, and Akiyama summited at 5:13 pm via a new route, after a grueling climb through the Silver Plateau and a steep summit wall. They faced exhaustion and worsening weather but reached the top.

The descent was tough, with a bivouac at 7,700m in a snowstorm. The team returned to Camp 4 after 39 hours and reached Base Camp on July 28 amid bad weather. Despite injuries and setbacks, the expedition succeeded, marking a new route on Nanga Parbat’s North Face.

This marked the third successful ascent of the Rakhiot Face and introduced a more direct but equally challenging alternative to the Buhl Route. No further ascents of this route have been recorded.

The Rakhiot Wall, attempted by an Italian party in 2008. Photo: Barrabes

2008: a new route attempt

In the summer of 2008, Italian climbers Simon Kehrer, Walter Nones, and Karl Unterkircher attempted a new route via the Rakhiot Ice Wall.

The team arrived at Base Camp in late May, spending weeks acclimatizing and observing the Rakhiot Face, noting its avalanche-prone seracs and crevasses. On July 14, they began their summit push at 10 pm, hoping to minimize avalanche risk by climbing at night when it was coldest.

They cached a tent at 4,500m and began climbing again after midnight on July 15, navigating 60° ice and a near-vertical M4/5 mixed wall to 5,700m. After tackling deep snow and a serac, they reached 6,300m by 4 pm, where Unterkircher fell into a crevasse and died. Kehrer and Nones attempted a rescue but found his body buried under snow. Unable to recover it in dangerous conditions, they retrieved his gear and continued up.

Karl Unterkircher. Photo: Herbert Mussner

Opting against a risky descent, they climbed toward the Silver Plateau via a longer, easier route through avalanche-prone slopes and steep mixed terrain. A storm on July 17 slowed progress with waist-deep snow, forcing bivouacs at 6,650m, 6,800m, 7,000m, and 7,300m.

They reached 7,500m on July 21. On July 22–23, they skied down the Buhl route in poor visibility, surviving two avalanches. Eventually, a Pakistani Army helicopter airlifted them from 5,400m to Base Camp on July 24. Recovering Unterkircher’s body was deemed impossible.

The route, named Via Karl Unterkircher (3,000m, IV-V M4+ 70°-80°), was dedicated to their fallen friend.

Since its last ascent in 1995, the Rakhiot Face remains unclimbed to the summit. Of the 80 people who have died on Nanga Parbat, more than a third perished on the Rakhiot Face.

You can find the climbing history of the Diamir Face here, and the Rupal Face here.