The Crusades had been raging for over a century, and Christian forces were exhausted, with morale at an all-time low. Byzantine Emperor Kemnenos was at his wits’ end, facing deteriorating relations with the West and a failed foreign policy. Then, a mysterious letter appeared. Its writer, an enigmatic figure from a distant land, is the answer to Christian prayers. Prester John, a Christian monarch of immense power, wealth, and military might, introduces himself as the savior of the Christian world. But who was he, and where was he?

A mysterious arrival

In the early or mid-1100s, an unexpected visitor from the outskirts of Christendom arrived in Rome to meet Pope Callixtus II. He claimed he was the archbishop of India.

According to German chronicler Otto of Freising, this man was called Prester John. He was a priest-king who claimed descent from the Magi (the three kings present at Christ’s birth) and claimed to have defeated various Muslim strongholds with a great army. He was Nestorian, of a branch of Christianity considered theologically heretical.

No one believed this story, and it was dismissed until 1165 when his letter arrived with Emperor Manuel I Komnenos.

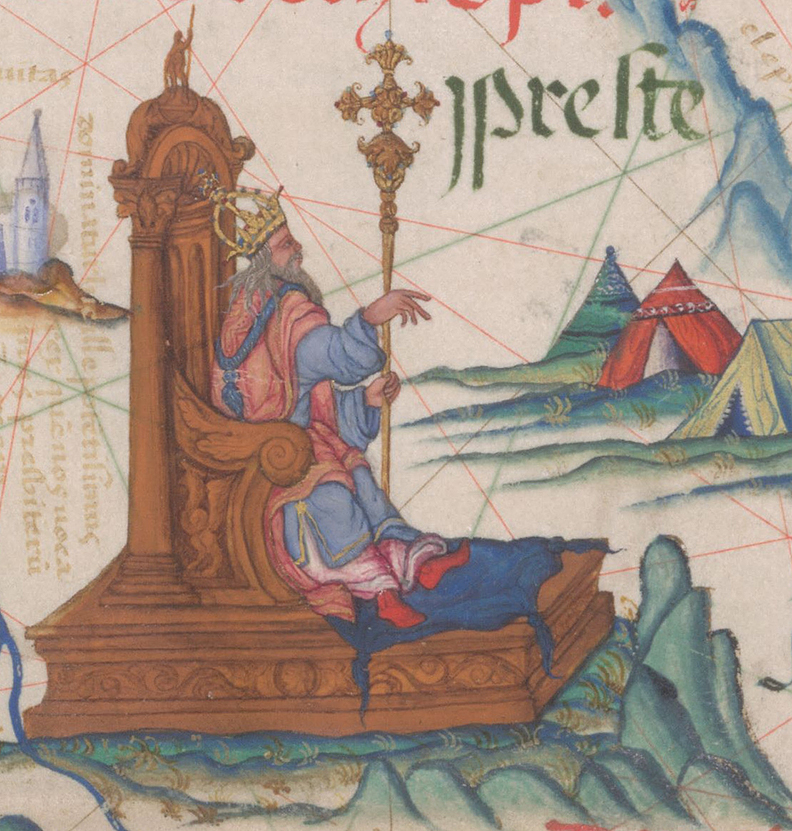

Prester John as Emperor of Ethiopia. Photo: Diogo Homem (1555-1559)

The letter

The 12th century also had its flamboyant self-marketers, and in his address to the Byzantine emperor in 1165, Prester John did not shy away from bold boasts. He elevates his status above all other kings:

Believe without hesitation that I, Prester John, am lord of lords and surpass, in all riches which are under the heaven, in virtue and in power, all the kings of the wide world…Seventy-two kings are tributaries to us. I am a devout Christian, and everywhere do we defend poor Christians, whom the empire of our clemency rules, and we sustain them with alms.

He goes on to refer to the Byzantine emperor as “governor of the Romans” and the Byzantines as “little Greeks.” He claims that his land is rich with exotic animals and that its people are sinless and almost immortal. Eagles supposedly brought special gems to the land that could restore eyesight, plants could cure people possessed by demons, sacred springs extended one’s life, and special charms could turn people invisible.

Prester John claimed to possess a magical mirror that allowed him to monitor all his citizens and foresee attacks from enemies. He boasted that his army numbered over 100,000:

When we proceed to war against our enemies, we have carried before our front line, in separate wagons, thirteen great and very tall crosses made of gold and precious stones in place of banners, and each one of these is followed by 10,000 mounted soldiers and 100,000 foot soldiers.

He vowed to storm the Holy Land and eradicate its enemies for Christendom.

Though we do not have reports of the Byzantine emperor’s reaction to the letter, the tale of Prester John spread rapidly across Europe. Other rulers, such as Frederick Barbarossa, also received letters. Pope Alexander III allegedly sent a letter to Prester John in 1177, requesting a meeting.

Prester John giving communion. Photo: Hartmann Schedel’s Nuremberg Chronicle, 1493

Location

Where did Prester John claim to rule? His empire allegedly consisted of “three Indies” comprising 72 provinces, whose kings and princes paid him homage as head of all rulers. He described his empire in the letters thus:

Our magnificence dominates the three Indies, and our land extends from farthest India, where the body of St. Thomas the Apostle rests, to the place where the sun rises, and returns by slopes to the Babylonian desert near the tower of Babel. Four months in one direction, indeed, in the other direction, no one knows how far our kingdom extends. If you can count the stars in heaven and the sand of the sea, then you can calculate the extent of our kingdom and our power.

Drawing heavily on some medieval bestiary, he also lists the country’s animals:

In our country are born and raised elephants, griffins, tigers, lamias, hyenas, wild oxen, archers, wild men, horned men, fauns, satyrs and women of the same kind, pigmies, dog-headed men, giants whose height is forty cubits, one-eyed men, cyclopes, and a bird, which is called the phoenix, and almost all kinds of animals that are under heaven.

In medieval times, knowledge of the world was limited. If a place lay beyond the borders of the known world, writers tended to supplement the lack of information with tales of pagan religions, great beasts, and half-human creatures. The letter depicts Prester John as master over all, both holy and pagan.

At the time, the term “Indies” usually referred not just to India but to Asia as a whole. But further in the letter, he mentions Mount Olympus as within his kingdom. Mount Olympus is in Greece, part of the Byzantine Empire.

Prester John depicted as an Ethiopian. Photo: Harvard Art Museum

There is also a theory that Prester John was from Abyssinia, modern-day Ethiopia and Eritrea. In the 1500s, when Europeans established diplomatic relations with Lebna Dengel, ruler of Ethiopia, they referred to him as Prester John.

A propaganda tool?

During the Crusades, there was much anti-Byzantine sentiment in Europe. The West thought itself superior, and crusaders often accused the Byzantines of not supporting the cause and secretly aiding Muslims. This put Emperor Kemnenos at odds with the West.

The Byzantines had a major problem with crusaders passing through their cities, behaving badly, and generally causing chaos. Therefore, historian Karl F. Helleiner believes the letter was a work of anti-Byzantine propaganda by political opponents, meant to undermine the Empire.

In the late 1200s, Marco Polo wrote about Prester John, claiming that Genghis Khan wanted to marry Prester John’s daughter. When Prester John refused, Genghis Khan invaded his country and killed him. However, Polo did not say Prester John was a Christian monarch but rather a king of the Keraites, also called the Nestorians.

Helleiner believes that the story of Prester John came from a king named Yeh-lü Ta-shih, who defeated the Seljuk Turks in a battle in 1141. To boost the morale of Christian crusaders, someone used the story and changed the king’s identity to serve their purpose.