On April 1, amateur metal detectorists Katarzyna Herdzik and Jacek Ukowski made a stunning discovery on a Polish beach. Their scanners led them to an ornate 24cm dagger covered in stars and crescent moons, approximately 2,800 years old. A few months earlier, outside Warsaw, a father and son came across a trove of rare 17th-century coins. These are just two of the many, many metal detector success stories out there.

Metal detecting is now a serious pastime for a growing number of people. Some great archaeological finds and treasures were turned up by those curious enough to poke around beaches, fields, and even waste lots. If you’re one of these, this is your ultimate guide.

The Polish duo’s find. Photo: Museum of the History of Kamień Land

History

Metal detecting began in the 1840s, when Henrich Wilhelm Dove invented the differential inductor. Its four coils, glass tubes, and copper wiring generated an electric shock when near metal.

Years later, in 1881, Alexander Graham Bell used a more developed version of the inductor to try to locate a bullet lodged in President James Garfield’s chest after he was shot by the deluded lawyer Charles J. Guiteau. Sadly, Bell was unable to find the bullet because of the metal bedsprings in Garfield’s bed. Garfield died of infection before Bell could figure out why his device did not work.

It wasn’t until the 1920s that Gerhard Fischer and Shirl Herr, working independently, created their versions of the hand-held electronic metal detector around the same time. Fischer, who received the patent first, initially created an aircraft radio direction finder. But when metal objects started to affect a pilot’s bearings, his focus shifted to finding the metals themselves. Fischer’s version used radio frequencies to determine the direction in which certain metals were. Meanwhile, Herr sought to find objects through the “production of sound waves effected by the distortion of a magnetic field.”

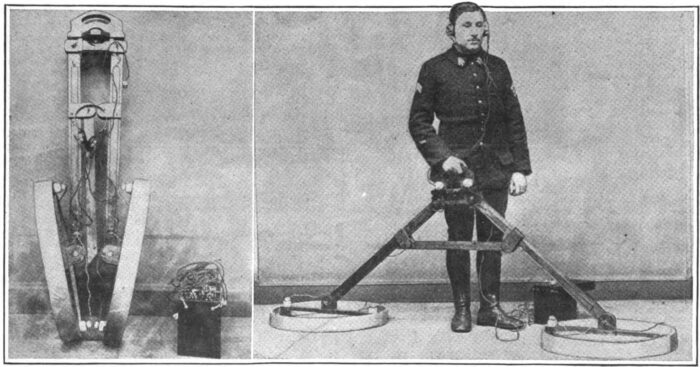

An early metal detector during WWI. Photo: F. Honoré

Herr’s version eventually made its way into the hands of the military, assisting Mussolini in recovering ancient artifacts. Richard Byrd also used it during his 1933 Antarctic expedition.

Fischer established a research lab bearing his name where he and his colleagues created the metallascope, a metal detector that became quite commonplace at archaeological sites, on the battlefield, and in construction to detect buried pipes.

How does it work?

In simple terms, a metal detector’s coil generates an electromagnetic field. When a metal object is nearby, it reacts to the field and gives off a current. When this current distorts the field, the receiver coil (another coil in the detector) alerts the user with either a sound or a visual cue.

Some metal detectors today often have a discrimination setting, allowing the user to distinguish between metals, as well as a setting for the type of soil nearby. The most advanced models include GPS, Wi-Fi, and Bluetooth.

There are several types of detectors. If you’re starting out, try a VLF (Very Low-Frequency) detector, which is the most common. These have a simple setup with two coils: one for sending signals and one for receiving them. With them, you can easily discriminate between metals, and you’ll have decent luck finding coins and jewelry. However, be prepared for an onslaught of bottle caps and unreliable results in highly mineralized or saline environments. You will need to adjust your settings accordingly.

More experienced searchers prefer a PI (Pulse Induction) detector. This uses pulse signals to penetrate the ground for deeper searches, even in mineralized and saline environments. If you’re searching for old relics, this is the detector for you. Keep in mind that PI detectors may be more powerful than VLF detectors but do not discriminate between metals.

If you’re looking for something specific, like searching for gold, a high-quality gold detector is your best option. Gold detectors can go deeper and withstand mineralization, but the cost can be challenging. In general, the price for metal detectors ranges from $250 to $2,000.

According to Metaldetector.com, some of the best on the market today are the Garrett ACE 400 ($339) for beginners, the Fisher F22 ($229) for all-weather conditions, and the Minelab GOLD Monster 1000 ($849) for gold. The XP Deus II ($1,449) ranks as the best all-around metal detector.

How to play by the rules

As with any hobby, there’s a certain etiquette involved. Most countries have instituted rules for metal detectorists now that real treasure is commonly discovered. By law, you can’t just waltz off with a hoard of priceless metals and historical artifacts. Please read the local or national laws before proceeding.

For example, the National Council For Metal Detecting in the UK states:

You must have the landowner’s permission to detect on any land. This includes parks, public spaces, woods, common land and public footpaths! Permission must be from the landowner (and the tenant if the land is leased)….

…Never, ever detect on protected sites. Important historical sites are scheduled, giving them legal protection. It’s a criminal offense to detect on them and you will be prosecuted if caught. Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) are also protected because of nesting birds, protected wildlife or rare fauna and flora…

…In England, Wales and NI, the landowner owns any non-treasure item found on their land unless they agree otherwise…

The UK has the Treasure Act of 1996, which states specific criteria for what treasure is and the protocol for when it is discovered. The finder must report the treasure to the local coroner. Once it is analyzed and declared treasure by the Treasure Valuation Committee, the finder and/or landowner receives a reward that depends on the value of the treasure.

Searching through the soil. Photo: Angyalosi Beata/Shutterstock

In Ireland, metal detecting is under strict control. According to the National Museum of Ireland:

The unregulated and inappropriate use of detection devices causes serious damage to Ireland’s archaeological heritage and is subject to severe penalties under the National Monuments Acts 1930 to 2014…

… It is illegal:

- to be in possession of a detection device at monuments and sites protected under the National Monuments Acts.

- to use a detection device to search for archaeological objects anywhere within the State or its territorial seas; without the prior written consent of the Minister for Culture, Heritage and the Gaeltacht.

In the United States, metal detecting is allowed, depending on state and local laws. For example, some state parks allow it, while others don’t. All activities fall under the Archaeological Resources Protection Act, which states:

No person may excavate, remove, damage, or otherwise alter or deface or attempt to excavate, remove, damage or otherwise alter or deface any archaeological resources located on public lands or Indian lands unless such activity is pursuant to a permit…

In general, depending on the country, metal detectorists get a finder’s fee, which is either the total value of the treasure or a percentage of it. To preserve the artifacts for public viewing or archaeological study, they don’t get to keep the treasure itself.

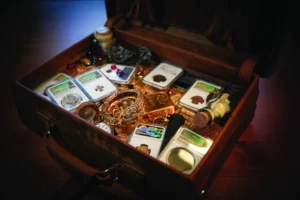

Staffordshire Hoard. Photo: David Rowan, Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery

Success stories

Many of the greatest historical finds today have come thanks to metal detectors. The so-called “world’s greatest treasure hunter,” Mel Fisher, grew up obsessed with finding treasure. He and his family spent the greatest part of their lives searching for the shipwrecks of the famed 1622 Treasure Fleet, in which all 11 ships sank during a hurricane off the southeastern coast of Florida. Fisher and a friend developed a metal detector that was retrofitted from a World War II submarine detection device. He also created a “mailbox” contraption that was able to poke holes in the seafloor and scoop up anything that may be hiding beneath the sand.

He found over a thousand gold coins during one haul after almost a year. Though he acquired quite a bit of money from finding the gold, the money dried up fast as his obsession with treasure-hunting took him and his family beyond their financial means. However, the hard work eventually paid off.

In the early 2000s, he and a company called Aquasurvey created a large-scale metal detector/sled that scoured the ocean floor. It was around 540kg and managed to find silver bars, anchors, cannons, and other submerged relics. Fisher also found the treasure ships Nuestra Señora de Atocha and Santa Margarita. When Fisher and his team found the Atocha, they received 75% of $450 million after a lengthy court battle with the state. The remaining 25% went to the State of Florida.

The Staffordshire Hoard

In the UK, a metal detectorist named Terry Herbert found the famed Staffordshire Hoard, which contains 4,600 gold and silver objects and precious stones, while combing a field in Hammerwich. After reporting his find to the coroner, authorities excavated. The excavations took over three years to find all these pieces, which were worth $4.3 million.

The largest gold nugget ever found in the Western Hemisphere is the Boot of Cortez. An amateur metal detectorist found it in Mexico’s Sonoran Desert. Resembling a boot and measuring more than 25cm high, the Boot of Cortez initially sold for a mere $30,000 because its discoverer did not recognize its true worth. It later sold at auction for $1.5 million.