As we reported yesterday, a polar bear attacked a skier in Auyuittuq National Park on Baffin Island last week. Details are scant, but the skier was evidently injured but all right. Authorities later shot the bear.

Several of our readers commented on the incident. “It amazes me how people can be so lacking in common sense,” wrote someone who identified as Jennifer. “You are trespassing on the polar bear’s home, yet you blame them when you’re attacked… If you stay away from them in the first place, you would not be attacked. It’s simple, stay out of their habitat.”

“Why would anyone kill the bear??” said Andrew. “He’s living in his habitat, and people are invading it. Terrible!!!”

“With polar bears now endangered and their habitat rapidly shrinking through no fault of their own, this isn’t really acceptable,” agreed MW.

Not the bear’s fault

A similar article in Baffin Island’s own Nunatsiaq News also drew several comments. Note that not all readers of this Arctic newspaper are Inuit, or even live in the north.

“This was 100 percent not the bear’s fault, as it was obviously not a predatory attack,” wrote Terry Sigurdson. “The bear was most likely protecting cubs or startled…Sad ending to a preventable situation.”

“If you’re stupid enough to go into bear or other wildlife country to ski or whatever when you are only concerned about having fun, you deserve whatever wildlife does to you,” said another.

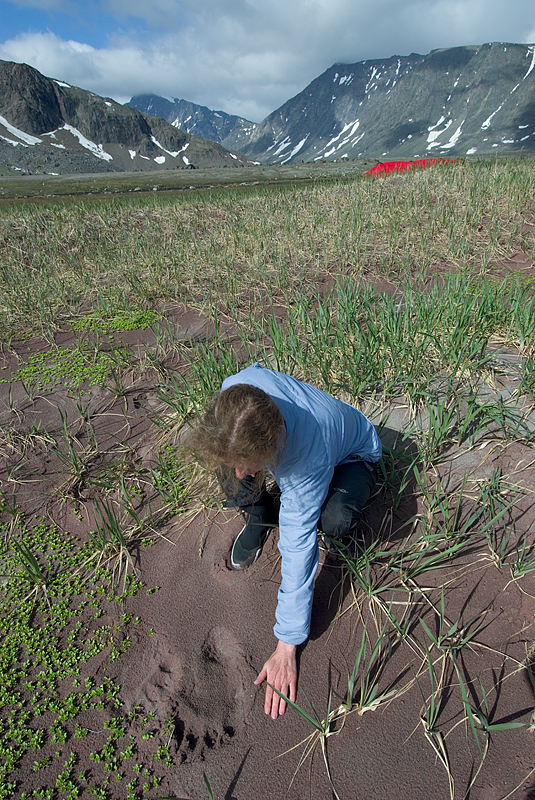

A camper beside a fresh polar bear print. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

No firearms?

Finally, two readers took issue with Parks Canada’s rule, mentioned in the Nunatsiaq News story, that non-Inuit are not allowed to carry firearms in Arctic national parks.

“This is wrong in so many ways,” said one. “Baffin Island is not Banff. This polar bear attack is 100% the fault of Parks Canada and their crazy rules.”

“I completely agree,” said another. “They should be held liable for any polar bear attacks. It’s crazy to think that in Svalbard, they don’t allow people to step into polar bear territory without a gun, and here they’re forcing hikers to expose themselves to danger by not carrying one.”

There’s a lot to unpack here. Let’s try.

I may be the editor of ExplorersWeb, but I’m also an Arctic traveler who has had over a dozen close calls with polar bears. I’ve never had to kill one, but it’s been close — for both of us. So my perspective will be affected by my experiences and by the fact that I’ve chosen to travel the Arctic independently in the first place.

Claw holes from where a polar bear gently investigated a tent. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

I do carry a firearm, and although I once went without one in an Arctic park where polar bears were historically rare, it was an uncomfortable gamble. Polar bears are great explorers and can show up anywhere, anytime. A tour group discovered this about 20 years ago, when a polar bear nosed around their camp on northern Ellesmere Island — in a spot where polar bears had never been seen before.

A hiking tour group had a shock in 2006 when a polar bear poked around their camp at Tanquary Fiord, Ellesmere Island. It was in a national park, and the guides did not have a firearm. Fortunately, no one was injured. Photo: Black Feather

Vulnerable vs endangered

A few small corrections of the readers’ comments:

- Polar bears are not endangered, they’re vulnerable — a still-concerning but less dire classification. Some populations, such as the one in western Hudson Bay, are more affected by climate change than others. Other populations are doing well. There are more polar bears off the coast of northern Labrador than there have ever been in historic memory.

- It is certainly not obvious, especially given the paucity of details, whether the incident in Auyuittuq last week was or wasn’t a predatory attack. Humans are very different from a polar bear’s usual prey, which is seals. Most polar bears want nothing to do with us. They run away, or amble off in that dignified bear manner. Polar bears are, however, one of the two animals in North America that occasionally stalk people as food. (The other is the cougar.) Typically, an interested polar bear approaches slowly, trying to make up its mind about you. “Is this something that might injure me, or should I make a play for it?” Adolescent males — cocky like human adolescents, still poor seal hunters — are the worst offenders; almost all my incidents have been with them. However, as Russian polar bear biologist Nikita Ovsyanikov once explained to me, polar bears are among the world’s most conservative animals. Ovsyanikov became famous for walking around polar bears with just a long stick and an attitude. With an confident attitude (feigned, of course), they are relatively easy to scare away with non-lethal deterrents like flares or bear spray. A warning shot sometimes works too, though not always. But while it is not possible to say anything about the incident on Baffin Island, I would not classify most of my close calls with polar bears as “predatory attacks.” Mostly, they feel as if the polar bear is probing, to see if an escalation is justified.

A polar bear patrolling a beach detoured to investigate a campsite in northern Labrador. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

Cubs not an issue

- Nor is it likely that the polar bear was “protecting its cubs.” That’s a potential issue with black bears and grizzlies surprised in the confined spaces of the southern woods. In the open Arctic, both parties tend to see each other coming, and a polar bear simply moves off.

Photo: Jerry Kobalenko

- As one reader of Nunatsiaq News pointed out, authorities killed the bear not as capital punishment for the crime of injuring a person, but because such an encounter can lessen a bear’s fear of people and lead to other, more deadly incidents. Down south or up north, this is pretty standard wildlife management following any animal-human clash. It’s one reason why responsible outdoor people need to take pains to avoid these in the first place — eg. by not feeding wildlife. The person may survive, but the animal is certainly doomed.

- Finally, it is a common misconception that anyone who goes out on the land in Svalbard, those polar bear-rich Arctic islands off the coast of Norway, must carry a firearm. That was never the case; it was just strongly recommended. In recent years, it’s become a little more time-consuming for foreigners to acquire a firearm permit.

For ‘fun’

Some have criticized the skier for being up there at all, potentially risking the life of a polar bear for “fun.” The implication is that nature is great, but only without people. We inevitably gum up the works, so we should stay in our cities and leave the animals safe and unmolested in their shrinking domain. One can disagree with that, but it’s impossible to argue against it, because it’s essentially a religious position.

There have been a couple of cases in the Canadian Arctic where adventurers behaved badly and caused the death of a polar bear. Years ago, a Swiss man named Markus Bischoff let a bear come too close during a solo dogsledding adventure so he could get better photos. The bear may then have come too close, and Bischoff shot the bear. He was later charged.

A photographer in Churchill, Manitoba, who was not paying attention, was chased around his truck by a polar bear. Another photographer filmed the close call. The man managed to take refuge in his vehicle.

Photo: Instagram

Minimize risk

There are many ways to minimize the risks of a polar bear encounter that can go badly for one or both parties. However, if you travel the Arctic enough, you will eventually see polar bears, and almost certainly have to deal with a too-curious one. You can’t go into polar bear country with the woo-woo attitude that Timothy Treadwell had with his grizzlies in Alaska. You have to be prepared to defend yourself — while at the same time, recognizing what a failure shooting a polar bear would be, and to do everything possible to avoid it.

Withdraw or approach? A polar bear tries to decide. Photo: Jerry Kobalenko