Four French climbers summited K2 without oxygen on July 28, including Benjamin Vedrines in a record 11 hours. Since then, they’ve been surprisingly tight-lipped about how they went down. Finally, the four fliers have left Pakistan and have revealed that they all flew down from the summit, despite the apparent ban on paragliding after the death of a Brazilian cross-country pilot.

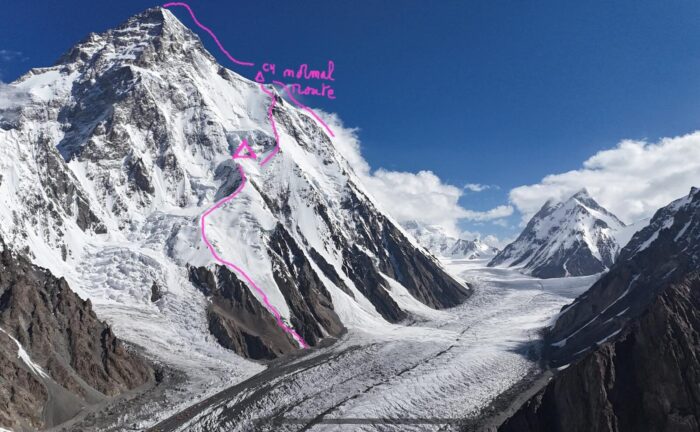

Jean Yves Fredriksen, known as Blutch among his friends, was one of the four. His K2 climb was extraordinary for reasons other than his descent. He followed a combination of routes, linking the Polish line (the central rib of the South Face), the tricky Messner Traverse, and the Cesen route (SSE spur) alone during a non-stop, 39-hour push. “I just hate crowds,” he explained simply.

Topo of Fredriksen’s approximate route. Photo: Jean Yves Fredriksen

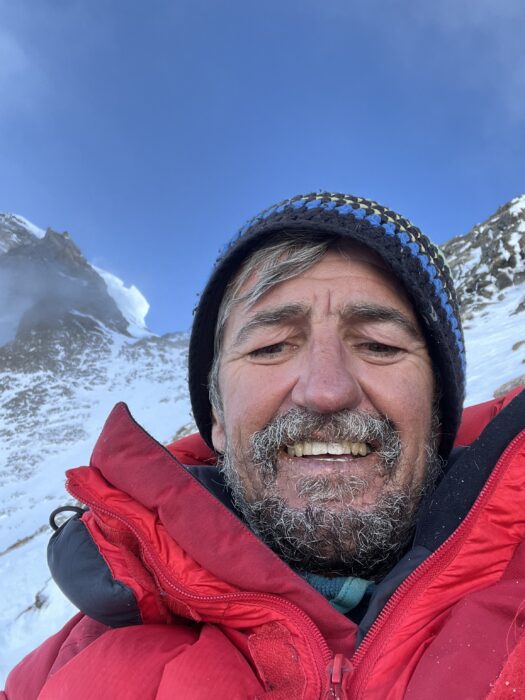

The 49-year-old climber is a paragliding celebrity, an extreme skier, an alpinist, and even a musician who plays his violin on every expedition. For years, he had dreamed of climbing K2, then cycling across the Tibetan plateau and repeating the climb+paraglide on Everest’s North Side.

“But the situation in China is complex, so finally I decided to focus only on K2,” he explained.

This spring, Fredriksen shared Base Camp with Vedrines and photographer Seb Montaz, and with Liv Sansoz and Seb Roche. All four had separate climbing plans.

A different acclimatization

Fredriksen, in particular, followed a different acclimatization method, going up and down to the one camp he pitched. It was at 6,600m, just before the Messner Traverse. This is the most dangerous section of the route because a big serac hangs above it.

“I went up and down about seven times, hoping for a summit chance, but either conditions or bad weather pushed me back down,” he explained, citing the unusually heavy snow this year.

Fredriksen didn’t want to do the Messner Traverse more than once. He never intended to rotate to any higher altitude.

“I belong to the school of Jean Troillet of Switzerland [a regular climbing partner of Erhard Loretan], with whom I was lucky to climb in the Himalaya. They always acclimatized between 6,000m and 7,000m but never slept at that altitude. Once acclimatized, they went for fast summit pushes.”

Fredriksen plays the violin at K2 Base Camp. Photo: Jean Yves Fredriksen

He discussed that approach in Base Camp with the other climbers. They advocated for sleeping at Camp 3 or Camp 4. “That is definitely not my way of climbing,” Fredriksen said. “After all, the summit of K2 is just 2,000m higher than my high camp. I gain more altitude when I am in Chamonix and climb Mont Blanc.

Every time he went up, he carried his ultra-light paraglider on his back.

“The paraglider is my rope, my backup,” said Fredriksen. “With it on my back, I am sure that, if anything happens, I can always escape and fly back down.” Fredriksen’s ultralight paraglider weighed just one kilo, not counting his 300gm harness.

He did not select a line ahead of time. Rather, he adapted to the conditions as he climbed. His only stipulation was not to follow the crowds.

The summit push

Eventually, a small weather window opened and put everyone in K2 Base Camp on the move.

“The snow was still very deep, but the weather forecast was excellent,” he said. “On my summit day, there was zero wind, and the temperature was very nice.”

Fredriksen set off from Base Camp on July 26 and slept in his one camp before the final push.

“On the 27th, I started with the daylight at around 5am,,” he said. “I didn’t want to do the Messner Traverse in the dark. It only took 10-15 minutes, but got me under that horrible icefall. Once safely on the other side, I climbed for two more hours in deep snow until I reached the Cesen route at some 6,900m.”

Rubbish at Camp 3 on the Cesen route during Fredriksen’s ascent. Phooto: Jean Yves Fredriksen

On the Cesen, Fredriksen found some old fixed ropes from the 2019 expedition, the last to attempt this route. He followed them until 7,200m. “From that point, there was nothing,” he noted.

Fredriksen followed a couloir for an hour, but it proved a dead end because of too much snow. He had to retreat and followed a rocky section to the right instead. It eventually led him to the normal Abruzzi Spur route at nearly Camp 4. By now, it was around midnight. He continued without sleeping. (He carried no sleeping bag or tent anyway.) By then, the Nepalese and Pakistanis, along with their clients, were ahead of him, so he didn’t have to break the trail anymore.

“I didn’t sleep but I did stop three times to melt some snow and hydrate. This time, I took a stove with me,” Fredriksen said. “For instance, I stopped before traversing the Great Serac. I saw climbers queuing there, so I opted for a 30-minute break and drinking while they moved along.”

Fredriken reached the summit at 3 pm. He stopped some meters away and dozed off, while Naoko Watanabe of Japan and her Sherpa guide took their own summit pictures and then left. It was time to fly down, but there was a problem: Zero wind is great for climbing at high altitude, but not for flying down.

Fredriksen on the summit of K2 without gloves. Photo: Jean Yves Fredriksen

Hoping for wind

“The take-off was very difficult due to the absolute lack of wind,” Fredriksen said. “I spent some 90 minutes trying, but the paraglider didn’t inflate enough to hold me. Finally, a gust of wind came and it was just enough to hold me.”

Fredriksen flew one minute north into China, then turned right along the east face and then right in front of the Bottleneck.

The Bottleneck and the South Face from the air. Photo: Jean Yves Fredriksen

At 6,800m, there was a thick layer of clouds, so Fredriksen had to look for a gap in order to keep descending with some visibility. “Luckily, I did a 360 and found a small hole in the mass of clouds right by the South Face,” Fredriksen said. “It was amazing.”

Looking for a gap in the sea of clouds. Photo: Jean Yves Fredriksen

He said the fog was 100m thick and then suddenly disappeared. “Then I saw my camp and my footprints in the snow on the Cesen route,” Fredriksen said.

He landed in soft snow, five meters away from his tent at 6,600m, after a 20-minute flight from the summit.

No way to hide

Frederiksen confirmed that Vedrines had launched some two hours before him, and that he met Sansoz and Roche on top. They got there shortly before Fredriksen left. An Italian climber on the summit that helped the other pair on their take-off.

How can you hide yourself when flying from the top of K2 with so many teams around? As far as everyone knew, paragliding was not permitted at the time. Moreover, Fredriksen confirmed they flew many times during the expedition, before and after authorities banned paragliding.

“We were very discreet, never showed off or told anyone, and we flew very early in the morning or at night,” he said. Yet he admitted that some people in Base Camp told the liaison officer, who checked his gear for paragliders. “However, the LO didn’t come to us after we descended from the summit,” Fredriksen said.

Fredriksen describes July 28 as a magical day. Photo: Jean Yves Fredriksen

The question remains, whether Pakistani authorities will react. The climbers risk being banned not only from paragliding but from climbing in the country. Officials took the matter seriously after the accident of Brazilian pilot Rodrigo Raineri, who had allegedly flown before his team’s NOC (No Objection Certificate) came through. It ended in a major mess, including the arrest of the expedition outfitter, Ali Saltoro, of Alpine Adventure Guides for several days.