Let’s get something out of the way right off the bat. Aliens did not build the pyramids, nor did a lost, technologically advanced civilization. It was ancient Egyptians using low-tech but highly exact engineering and a whole lot of manpower.

But because the Egyptians didn’t leave many records about the details of their grand construction projects, there are still some unsolved mysteries about how, precisely, they did it.

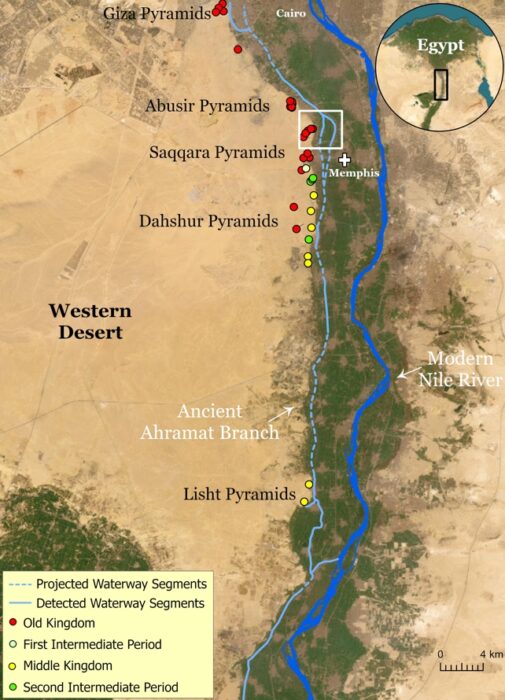

One of those mysteries involves location and logistics: Why did the Egyptians build 31 pyramids along a narrow desert strip relatively far from the Nile? After all, using the easily navigable river to transport and manage the vast quantities of stone, workers, animals, food, and water needed to raise their monumental tombs would have been far simpler than transporting all those things overland.

This would have been a lot easier with a waterway nearby, don’t you think? Photo: Shutterstock

Nile tributary

Researchers have long believed the answer lay in a theoretical waterway that ceased to exist at some point in the distant past.

But, “nobody was certain of the location, the shape, the size or proximity of this mega waterway to the actual pyramids site,” Eman Ghoneim of the University of North Carolina Wilmington told the BBC.

Ghoneim is part of a team that thinks it’s finally solved the puzzle. Using a combination of techniques, including historical maps, sediment coring, geophysical surveys, and radar satellite imagery, the scientists discovered a 64km long branch of the Nile that vanished thousands of years ago — but was most likely still flowing strong when the 31 pyramids were built.

The scientists published their research in the journal Communications Earth and Environment.

Map: Eman Ghoneim et al, University of North Carolina Wilmington

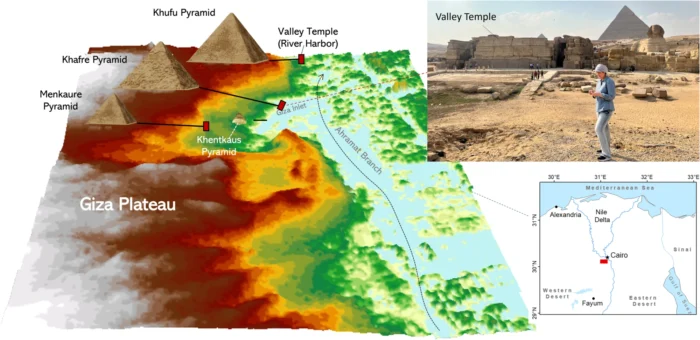

The team dubbed the extinct branch Ahramat, an Arabic word for pyramid. The lost waterway included a major inlet that would have made transporting and unloading stone and workers much, much easier than the alternative — manhauling blocks across the desert.

Ancient drought

However, as the ancient Egyptians knew better than almost anyone, all good things must come to an end. In their paper, the researchers speculate that a drought beginning roughly 4,200 years ago might have caused Ahramat to dry up. But before it vanished, it likely changed course.

“So fourth-dynasty kings had to make different choices [about pyramid location] than 12th-dynasty kings,” co-author Suzanne Onstine, University of Memphis, told ScienceAlert.

Map, illustration, photo: Eman Ghoneim et al, University of North Carolina Wilmington

So that’s one pyramid mystery down. Now if only we could solve the spiral ramp vs. linear ramp debate!