In 1630, eight little-known Englishmen were separated from their expedition and became stranded on Spitsbergen, in the European High Arctic north of Scandinavia. They had to overwinter with no ship, no navigation equipment, and scant supplies. Nevertheless they accomplished, however accidentally, the first successful overwintering on Spitsbergen.

One of the men, Edward Pellham, wrote afterward that the earlier sufferings of famed explorer Willem Barentsz and his men on Novaya Zemlya, in which Barentsz lost his life, were nothing compared to their lesser known ordeal. “If…the Dutchmen’s deliverance were worthily accounted a wonder,” he wrote, “ours can amount to little less than a miracle.”

A woodcut showing Barentsz and his men in their (according to Pellham) comparatively warm and well-provided shelter. Photo: Illustration from a 17th century printed account of the voyage

Separated from the fleet

On May 1, 1630, the Salutation set sail from England, one of three Muscovy Trading Company merchant ships bound for the Arctic. In the summer, the Company sent ships northwards to catch whales, trade with Russia, and unsuccessfully attempt to penetrate the Northwest Passage.

The trio of ships, led by Captain William Goodlad of the Salutation, reached the Arctic in June. Goodlad was a sturdy, experienced whaling captain who had served the Muscovy Company as their whaling fleet admiral since 1620. What we know of his career is storied; his own brother had died on one of his expeditions, tangled in a line and dragged out of his boat by a whale. On multiple occasions he’d led violent skirmishes against rival whalers, defending his company’s royal monopoly on whaling in the region.

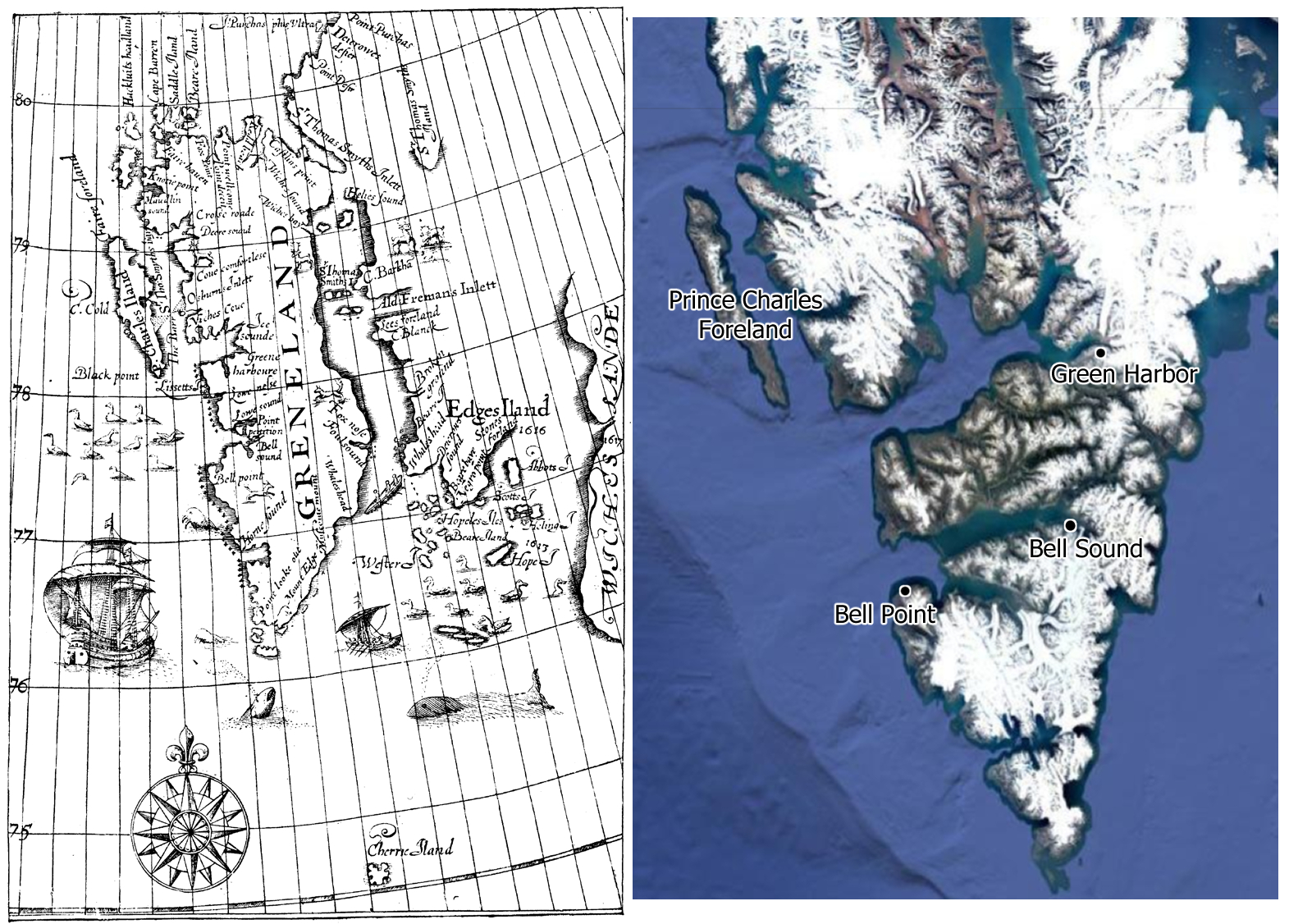

Goodlad split up his ships when they reached Prince Charles Foreland in Spitsbergen, with the Salutation remaining there. On August 8, Goodlad decided to head for the whaling camp of Green Harbor. Contrary winds, however, prevented southward progress. Goodlad decided to make the best of the situation. There was a hill a bit inland, about 20 kilometers from their current position, which was known to be thick with reindeer.

Goodlad chose eight men for the task, in a shallop (a small, shallow-draft boat about nine meters long) for the short trip. He had no idea that he would be returning to England without them.

Arctic whalers in the mid-17th century. Photo: Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Separated from their ship

We’ve already met one of the men aboard, Edward Pellham, a gunner’s mate. His companions were his direct supervisor, the gunner William Fakely, Heny Bett the cooper, Thomas Ayers, a whale-cutter, sailors John Wise and Robert Goodfellow, and two landsmen named Richard Kellet and John Dawes.

They expected to be gone only a few days, so they didn’t take much in the way of supplies or gear. The shallop was loaded with two whaling lances, a tinder box, a snaphance (an early cousin of the flintlock), and a pair of hunting dogs. Without incident, the party reached shore and spent the day hunting, planning to rest overnight and then return to the ship.

The weather, predictably, turned. When they woke up, they realized the wind had forced their ship far out to sea to avoid being driven onto the rocks. With no way to navigate or communicate, they decided the safest course was to make for Green Harbor, where Captain Goodlad would hopefully be waiting. But when they arrived, they found that the ship had already left.

Left: A map of Spitsbergen, which was then considered to be the lower part of Greenland, made by the Muscovy Company in the early 17th century. Right: Spitsbergen, the largest island in the Svalbard archipelago, with relevant locations highlighted. Photo: Google Maps/modified by author

Abandoned in the Arctic

Things were now becoming serious. The entire fleet was planning to head back to England on August 20, leaving them only three days to find the ship. The fleet was supposed to meet at Bell Harbor for their final departure. That rendezvous was the group’s last and best chance. That meant moving quickly. In a desperate gamble, the group threw overboard all the venison they’d stored to lighten the shallop.

That day, they reached the halfway point, called Low-Nesse, where fog forced a pause. The next morning, they pressed on, quickly covering the distance to Bell Point. But they missed it in the fog, continuing far past. Pellham and some of the others began to worry; they’d been rowing and sailing for too long.

But only one of them had been to Spitsbergen before, and that was Pellham’s supervisor, William Fakely. Fakely insisted that Bell Sound was still further south and, convinced by his experience, they pushed on further and further past their destination. The doubters briefly prevailed, heading back north to within a few kilometers of Bell Sound. But Fakely again insisted they were going the wrong way, and so the shallop reversed course again.

Eventually, Pellham had to physically wrestle the oar out of Fakely’s hands to get them moving in the right direction. They reached Bell Sound, but too late. It was August 21, and the fleet was gone.

Modern recreation of an early 17th-century shallop. This one was modeled after the shallop belonging to the ‘Mayflower’. Photo: Plimoth Patuxet Museum

Desperate preparations

Sure, the whaling fleet visited the area regularly, but that was in the summer. No one, they thought, would be insane enough to winter in the Arctic. Explorers who did become trapped, like Hugh Willoughby and the aforementioned Barentsz, suffered greatly and often died. In fact, this wasn’t the first time the Muscovy fleet under Captain Goodlad had left people behind. Pellham recalled that in a previous year, nine men had tried to overwinter in Spitsbergen and all had perished.

They had no choice but to prepare as best they could. They decided to make for Green Harbor, where there were more reindeer. Probably regretting dumping all their food overboard, they organized parties to hunt and store up as much venison as they could.

Winter, however, was coming on in earnest. A storm capsized the boat, again sending their provisions into the sea, and soon the ice was too thick to risk the journey between Green Harbor and Bell Sound. Working quickly, they used their boat and what was available around the abandoned whaling station to build a shelter.

Fakely and Pellham, forgetting their animosity, deconstructed the furnaces for rendering whale oil brick by brick to build walls. To keep their mortar from freezing, they had to keep multiple fires going at all times. They built their brick shelter inside of a larger preexisting structure, a clever double-insulated design, and stored as much wood from old barrels and wrecked boats as they could. There was nothing more that they could do, other than conserve their supplies and wait.

The remains of a 17th-century tryworks or blubber processing oven, like the one Fakely and Pellham repurposed. Photo: “Blubber Oven” by David Stanley, CC BY 2.0

Cold, dark, and hungry

While they were active, they managed to avoid despair. But by October 10, the sea was frozen, the sun had almost disappeared for the winter, and they had little to do but complain.

“Our heads,” Pellham wrote, “began then to be troubled with a thousand sorts of imaginations.”

While they sat huddled, in one breath cursing Captain Goodlad and in another praying for his salvation, they lived on short rations. They agreed to eat only one meal a day, and to fast on Wednesdays and Fridays. On these days, they only had what were called “fritters” of “graves of the whale,” scraps of whale fat discarded after the oil was extracted.

Thus tormented in mind with doubts, our fears and our griefs; and in our bodies with hunger, cold and wants…

As the winter went on and supplies ran thin, they added two more fasting days to the schedule. The extreme darkness was very difficult mentally, and they attempted to lessen it by constructing little lamps with reflective scraps.

Eventually, the light began slowly to return, but the cold got worse. After going outside for a few minutes to fetch snow to melt for drinking, Pellham felt as sore as if he’d been physically beaten. Their fingers blistered with frostbite. Though they tried to improve their situation and prayed several times a day, Pellham admits that none of them really believed that they would survive.

Late 19th-century depiction of the summer midnight sun in Bellsund, which Pellham calls by the older English name, Bell Sound. Photo: Library of Congress

Bear incursions

By the end of January, the sun was back, but this was little comfort. They had taken stock of their food supplies and found that even on their already short rations, they had six weeks of food left at most.

With the light came the polar bears, both a blessing and a curse for the stranded crew. The bears were a potential source of food, but, as Pellham wrote, it was a toss of the dice “which should be eaten first, we or the bears, when we first saw one another… They had as good hopes to devour us, as we to kill them.”

They learned the hard lesson of many Arctic hunters after successfully killing their first ursine intruder. Polar bear liver is dangerously high in vitamin A, and eating even a bit can be fatal. Luckily, none of them died, but they did become quite ill, with their skin peeling off. Don’t eat polar bear liver!

Over the next few months, nearly 40 bears stopped by, trying to figure out if these strange Englishmen tasted anything like seals. The men killed a further seven, solving their food problem, and managed to scare off the others. The bears probably did manage to get some of their own back. On March 16, Pellham records, one of their two dogs disappeared.

A life-saving source of food. But watch out! Photo: Shutterstock

Spring and rescue

To their collective shock, the eight men began to realize, as the days grew longer and birds, foxes, and deer started to return, that spring was coming. The impossible had happened: they had survived the winter, nearly two degrees further north than Barentsz, and much worse supplied.

By May, they began looking out to sea, checking for the ice-free water that would allow ships to enter the sound. On May 25, however, they stayed inside the shelter due to nasty offshore winds. That wind had, actually, blown all the ice out to sea, and that very day two ships from the port of Hull sailed into the sound. The Hull fleet was not supposed to be in Spitsbergen. Only a few years earlier, Captain Goodlad had driven them out at cannon-point.

But they had heard that some men had been abandoned the year before, and couldn’t help but go and see if the men had lived. Our company, meanwhile, was gathered close together in the warm inner room. Only Thomas Ayers, still in the outer, heard a faint “Hey!”

Astonished, he called back. Soon, all eight were piling from the shelter. Their clothes were in tatters, their bodies blackened with oily smoke. The Hull men took them aboard, promising to house and feed them while they waited for the Muscovy fleet.

A 17th-century Arctic whaling fleet. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Reunited and immortalized

Captain Goodlad arrived a few days later, relieved to find his men alive. Pellham praises Goodlad, who treated the rescued men as conquering heroes. He paid for new clothes out of his pocket, gave the landsmen a raise, and threw open the larders to fatten them up again.

Fakely, John Wyse, Thomas Ayers, and Robert Goodfellow transferred to another ship, commanded by Captain Mason. Unlike Goodlad, Mason accused them of being runaways and harangued the exhausted survivors. Goodlad tried to get them transferred back to his ship, but the weather prevented it.

A grateful Pellham, meanwhile, spent the rest of the season whaling on Goodlad’s ship as usual. In late August, the fleet finally headed home. Pellham wrote his pamphlet, dedicating it to the Muscovy Company governor. From this, I assume that he intended to continue working with them, but I was unable to find firm details on what became of him.

I’ll leave you with the ridiculously long title of Pellham’s pamphlet. Try, if you can, to read it aloud without taking a breath.

God’s Power and Providence: Shewed, In the Miraculous Preservation and Deliverance of eight Englishmen, left by mischance in Green-land Anno 1630, nine moneths and twelve dayes. With a true Relation of all their miseries, their shifts and hardship they were put to, their food et cetera, such as neither Heathen nor Christian men ever before endured. With a Description of the chiefe Places and Rarities of that barren and cold countrey. Faithfully reported by Edward Pellham, one of the eight men aforesaid. As also with a Map of Green-land.