The images of Andrzej Bargiel of Poland skiing down a lonely, snowy Everest, on the first complete descent without supplementary oxygen, have made headlines around the world. However, until now, we know very little about the strategy and the work that made it possible.

Here is Bargiel’s detailed explanation of his ski descent of Everest, the future of high-altitude skiing amid climate change, and the legacy of those who skied Everest before him.

The strategy

Bargiel and his support team left Base Camp at 4:30 am on September 19 and reached the summit two days later, after a final push that took the big team 16 hours from Camp 4. Bargiel admitted to ExplorersWeb that he would have preferred a faster, lighter ascent, but the absence of other teams on the mountain (except for American runner Tyler Andrews’ small group) forced a different strategy.

Andrzej Bargiel climbing above camp 4 on Everest. Photo: Bartek Bargiel/Red Bull Content Pool

The original plan was a fast push from Base Camp to Camp 2, then from Camp 2 to the South Col, and from the South Col straight to the summit. Unfortunately, there was a lot of snow, as the monsoon lasted much longer than usual, and it was raining almost every day at BC.

With the high temperatures, the glacier was melting, forming convective clouds that kept bringing more rain. In those conditions, it’s simply impossible to attempt a speed ascent. Of course, I would have preferred to go directly from Camp 2 to the summit — that was the original idea — but it just wasn’t possible this time.

Sherpa support

The expedition included several photographers and cameramen (with hand-held cameras and drones), plus a large Sherpa team between Base Camp and Camp 2 — staff, porters, and climbers.

We started the summit push with 12 Sherpas. Unfortunately, after an incident — a snow slide — two of them couldn’t continue, and two members of the film crew had to stop as well. In the end, 12 of us, including one cameraman, reached the South Summit. We were fixing ropes as we climbed and opening the route. None of us had been higher before, so the route hadn’t been prepared.

Most of the team stayed at the South Summit, and I went with Dawa Sherpa to the top, fixing the last section of the route.

Andrzej Bargiel at Everest Base Camp. Photo: Bartek Pawlikowski/Red Bull Content Pool

It would have been very hard to make this expedition happen without the help of Seven Summit Treks and the support team. We knew we would be alone in Base Camp, so we had to build our own team — people who could help prepare and secure the route. I always take safety seriously and I knew we had to be self-sufficient, with a plan B and plan C ready.

Bargiel noted that they had an elaborate team.

Apart from my core team of nine people, including myself, we had four camera operators (one of them stayed at Base Camp) and a director, which made it a large-scale project. It was both a sports and a film production.

His brother Bartek and another cameraman shot from Camp 2.

The ropes

It’s quite amazing how special this season turned out to be. When people think of Everest, they usually picture long lines of climbers and crowds on the route. But we were completely alone. During the monsoon, a few meters of snow fall up high, covering everything. It changes the mountain completely — no human traces, no fixed ropes, no footprints. Everything was buried in fresh snow, and that made the place feel wild again.

Bargiel’s team fixed the ropes themselves, all the way to the summit. During spring, that laborious task is shared between the Icefall Doctors, who open a route up to Camp 1, and a second team that fixes ropes from Camp 2 to the summit.

We fixed ropes ourselves wherever we felt it was necessary for orientation and safety. I hardly used the ropes myself, as there was no real need. I climbed to the Col with poles, following sections where small slides had already cleared the snow, which actually made the approach easier. But we wanted the route to be properly secured so the team — including the Sherpa climbers and the three cameramen — could move safely and efficiently.

It was also important that, in case of cloud cover or low visibility, the fixed ropes on the section between the Col and the summit would provide safety and orientation.

A variation route

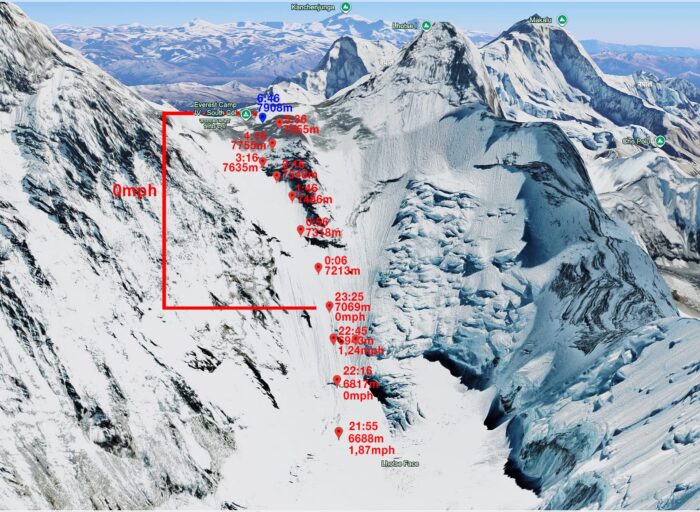

Tyler Andrews told us that the ski team climbed a different route from the bottom of the Lhotse Face to Camp 4. They went far to the left and followed a steeper, shorter line. Bargiel and Andrews never had a chance to meet, as the American runner reached Base Camp when the ski expedition had almost ended. But Bargiel confirmed these details.

Andrews’ route from Camp 2 to the South Col of Everest, according to his tracker. Topo compiled by @alpymon

From the start, we decided that the safest route would be the one to the left of the Geneva Spur couloir. That line, just left of the Geneva Spur ridge (looking up from below) leads directly to the South Col. We changed the route out of concerns about avalanches coming from the Lhotse Face couloir.

We didn’t set up Camp 3. The snow was lying on solid ice, and it was really hard to build a proper platform there. However, during my first acclimatization rotation, I bivouacked roughly at the height of Camp 3, an essential step in my acclimatization, and then removed the tent.

The chosen climbing line went between the South Pillar — partly following the Polish Route up to its base — and then straight up toward the South Col. It was a new variation for us, and a more interesting one from a skiing perspective.

The avalanche

While the beautiful photos and videos tell a story of triumph, the expedition also had a close call when an avalanche hit several members. Here is Bargiel’s account.

We tried to reach the summit on September 14. That night, around 20 centimeters of fresh snow fell. Unfortunately, part of the team started a bit too late, and a small snow slide broke loose somewhere halfway up the route to the South Col, just below the Geneva Spur. It hit the last four climbers on the slope.

They were below the bergschrund, right where the route breaks between Camp 2 and the wall. It was a real shock for them, but luckily nothing serious happened — no major injuries. Those four went back down to Camp 2.

We were higher up, and after confirming over the radio that everyone was safe, we continued our climb.

As mentioned above, the slide caught two Sherpas and two cameramen, who couldn’t continue. “Both had summited Everest before, so from the outset, we’d hoped they could push as high as possible for the footage,” Bargiel noted.

Andrzej Bargiel and Dawa Sherpa on the summit of Mount Everest on September 22. Photo: Bartek Bargiel/Red Bull Content Pool

The descent

And then, there was the descent, done all the way from the summit to Base Camp on skis, without rappelling. We asked Bargiel about the line, the most complex passages, and the hazards.

The summit ridge was definitely very snowy. There was a lot of fresh snow, so I had to be really careful. It was steep, and the snow there was slabby, so I had to be careful not to trigger a small slab slide. After that section, it was fine. The trickiest part was between the South Summit and just above the Hillary Step — the snow there was steep and heavy, and we really had to push hard to make progress. That section took us the most time.

The ski down was fine — I just slid down following the ridge line. Was it the hardest part? It definitely required focus, but I didn’t find it extremely difficult.

Andrzej Bargiel skis down the Hillary Step on Everest. Photo: Bartek Bargiel/Red Bull Content Pool

Further down, Bargiel skipped the most avalanche-prone section (the Lhotse Face) by skiing the same line he had used for the ascent.

As I mentioned, we climbed to the left of the Geneva Spur — up a couloir that led straight to the South Col — so the conditions there were actually quite good during the second summit push. During the first attempt, we had to turn back from the South Col because there was just too much snow.

But after a few days, things settled down, the snowpack stabilized, and the avalanche risk basically disappeared. During the second summit push, the snow was firm all the way up to the Col, so I could basically climb to the pass just using my poles.

Stop at Camp 2

Unlike a previous ski descent by Davo Karnicar, Bargiel stopped at Camp 2, not due to exhaustion, but for safety reasons: The Icefall was too unstable in the afternoon.

The stop at Camp 2 was planned from the beginning. After about 8 am, the [Icefall] became really dangerous, so if I wanted to ski through it safely, it had to be very early in the morning. That’s why I decided to spend the night in Camp 2. It was the only reasonable and safe way to make it work.

Bargiel described how avalanches were coming down from the Nuptse side and from Everest’s shoulder, near the Lho La, and how, by noon, the terrain on the glacier was collapsing. “You could easily end up in a crevasse,” he noted.

Both the schedule and line for the ski descent were chosen for safety. For Bargiel, getting caught in a slide on Everest while skiing was not an option.

I didn’t carry an avalanche backpack — on a face of that scale, it wouldn’t really make a difference. The idea from the start was not to move in dangerous conditions at all. That’s the whole concept: Avoid avalanche terrain, stay safe, and act only when conditions allow. That’s key. It’s different from the Alps, where we often ski with full avalanche gear — detector, probe, shovel — and sometimes accept a bit of risk. On Everest, you can’t do that. You just have to avoid it altogether.

Andrzej Bargiel skis down Mount Everest. Photo: East Studio/Red Bull Content Pool

The Icefall in the autumn

Autumn is really the only time when this ski descent is possible. The Icefall gets covered with snow — in spring it’s just too icy. I was also quite lucky, because the Icefall Doctors team was hesitant to fix ropes and open the route. For them, it’s a tough job at this time of year. In autumn, the conditions are so different that they don’t feel completely safe working there. The ice underneath is soft, like sugar.

Andrzej Bargiel skis through the Khumbu Icefall. Photo: Andrzej Bargiel / Red Bull Content Pool

Temperatures are higher, the ice isn’t solid, you can’t place screws properly — you have to dig anchors and bury your shovels deep in the snow to build a solid belay point. It takes a lot more effort and a very careful approach to secure the route. The Icefall Doctors basically pulled out from fixing the route — they didn’t go up with us, as they didn’t feel comfortable moving through that terrain.

Because of that, I got involved in fixing the ropes myself, and it actually helped me a lot in finding the ski line. By working on the route, I had a better sense of the terrain, could observe different parts of the glacier, and spot a possible line. It didn’t follow the fixed rope line exactly, but it was doable line.

The passage through

The amount of snow helped, but skiing down the Khumbu Icefall is still a formidable challenge, so we asked Bargiel for further details.

At the beginning, I followed a similar line to what Davo Karnicar took — below the Nuptse walls — then turned briefly toward Everest’s shoulder before cutting back left, under the huge serac hanging from Nuptse.

From there, I skied all the way down to the last patches of snow and ice, at Base Camp altitude. From that point, I had to walk to Base Camp, on glacial terrain but covered by loose rock and debris.

Andrzej Bargiel navigates the Khumbu Icefall. Photo: Bartek Bargiel/Red Bull Content Pool

For me, that was something really special. At first, I honestly didn’t believe it would be possible to ski down the Icefall. But every expedition teaches me that this glacier changes every season — it’s never the same. Each time, you have to approach it with fresh eyes and build everything from scratch.

Everest vs K2

Bargiel is the only person to have completed ski descents of the two highest peaks on Earth. He did both without bottled oxygen. We asked him to compare the experiences.

Everest was definitely harder in terms of overall effort — just to get to the summit. Autumn makes everything more demanding; the monsoon lasted longer, there was a lot of snow, and the amount of work we had to do was truly massive. It was a real grind.

K2 is 300 meters lower, and that makes a difference. There wasn’t nearly as much snow there. Otherwise, the K2 route was more technical, and it also required establishing almost a new line. I didn’t really follow the standard route, especially during the ski descent. That descent was really interesting — I connected a few different lines, which made it something unique. But it’s hard to compare the two.

On Everest, the main challenge is the physical effort. It’s just a tough mountain to climb. The glacier is complicated — not vertical, but a real maze — and you need to find your way through it, picking a line that safely leads you all the way back to Base Camp.

Watch Bargiel’s 2018 K2 descent below:

No pressure

This was Bargiel’s third attempt to ski Everest, and he spared no expense to bring it off. We asked him about the pressure that such an investment and complicated logistics entail, and the consequences of failure. However, he denied feeling any pressure.

For me, it’s more about a dream — a personal test. I just want to see how far I can go, how much my body can take, whether I’m able to handle that kind of altitude and still ski without oxygen. That was the whole idea — a challenge I set for myself.

My motivation has never been about racing anyone or trying to make history. It’s about passion — pushing my own limits and exploring how far it’s possible to go.

Andrzej Bargiel, back in Base Camp. Photo: Bartek Wlikowski/Red Bull Pull Content

Climate change

Previously, Bargiel mentioned he wanted to ski down Everest as soon as possible, because climate change would soon make it impossible. He says this new attempt confirms his suspicions.

The glacier has changed a lot since Davo Karnicar’s descent, and it’s definitely getting harder. The quality of the ice is worse every year. The glacier is shrinking, collapsing, breaking apart, and the conditions on Everest will just keep getting tougher each season for skiing.

These changes are really visible. I first came to Everest in 2012, and I can see it with my own eyes — the difference is huge. The weather is more unstable, pressure changes fast, strong winds come suddenly, heavy snowfalls hit more often…We simply have less and less time to move safely in the mountains and to chase our dreams up there.

A moment of the ski descent. photo: Andrzej Bargiel/Red Bull Content Pool

Adapting to rising temperatures

The increase in temperature was dramatic this year in the Karakoram, and fall expeditions there are also dealing with unusually unstable weather. For a skier, the changes in the weather patterns are especially important, says Bargiel.

You have to pay more and more attention now — really understand the conditions and use every short window when the weather allows you to move. During this expedition, I also knew I didn’t have much time. I had to act fast, because from my previous attempts, I knew that by the end of September, strong winds come in. Once they hit, it’s over. The wind brings snow, and when snow falls with the wind, the avalanche danger goes up quickly. The weather changes fast — it’s getting more and more unpredictable, and that makes everything harder.

I’d still love to keep skiing in many unique places, on different special peaks. I love exploring, I love challenges, and I hope there are still a few interesting things ahead of me — that I’ll be able to keep doing what I love. But for sure, climate change doesn’t make it easier. The risks are growing, especially for local guides, Sherpas, and all the people who work on the mountain.

Tribute to the pioneers

Bargiel emphasizes that this was a team effort, but he also paid homage to the pioneers of high-altitude skiing.

He singles out Hans Kammerlander, who made a valiant attempt to ski Everest in 1996.

“It was a partial one, but I believe the season just didn’t allow for a full descent,” he says. “It was in May, which made it even harder.”

Bargiel adds that Kammerlander climbed the mountain in a mind-blowing 16 hours and 45 minutes and skied down that same day.

He also highlights Davo Karnicar of Slovenia, who did the first complete ski descent of Everest, although he briefly used oxygen.

“He went all the way from the summit to Base Camp through the Icefall, which is a massive challenge.”

Finally, he had words for Fredrik Ericsson of Sweden. “He made me believe that skiing down from the highest peaks can be done. He worked in high mountains, had a great spirit, and inspired me to even try and dare to take on K2.”