Scientists closely study our planet’s polar regions to understand the overall changes in our climate. Loss of ice sheet volume has far-reaching effects, but is also difficult to predict. A team from Tokyo’s National Institute of Polar Research has published a paper in Nature, exploring the Holocene Antarctic collapse to understand what happened in the past after rapid ice sheet thinning.

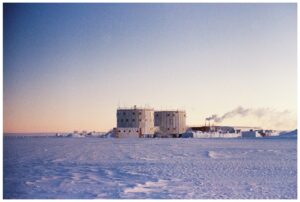

The National Institute of Polar Research team takes measurements in East Antarctica. Photo: Yuichi Aoyama/NIPR

Feedback loop

The East Antarctic Ice Sheet is the planet’s largest ice sheet. Here, the continent experienced significant ice loss and breakup after the end of the last Ice Age around 9,000 years ago. The NIPR team examined sediment cores from the seafloor, and the tiny fossils within them, to trace the breakup of the ice.

They discovered that melting ice caused a positive feedback loop. As the ice melted, the fresh surface water drove the warmer, saltier water toward Antarctica. This warmer water — called the Circumpolar Deep Water — melted the base of the ice shelves, leading to more freshwater ice melt.

Partly due to this positive feedback loop, the collapse of the East Antarctic ice sheet was very rapid. As the submerged ice wore away, the remaining sheet on top became thin and unstable. As soon as the outer ice shelf collapsed, the inland ice also thinned up to 100 kilometers inland.

Deep, warm waters on the coast of East Antarctica can accelerate ice loss. Photo: Suganuma et al

Meltwater modeling

This thinning peaked between nine and seven thousand years ago. Eventually, conditions changed, and the loss was reversed. But the paper’s authors believe this ancient event can improve our modern models of ice loss.

The bad news is that the more meltwater they added to the model, the thicker and warmer the Circumpolar Deep Water became, and the faster the ice sheet thinned.

During the early Holocene, changes in the ocean’s surface floor also caused rising sea levels. In another positive feedback loop effect, higher sea levels contributed to ice loss. The more buoyant the ice sheet, the more that deep, warm water ate away the sheet’s supports. This led to thinning ice, which led to more melt, which caused higher sea levels.

East Antarctica has long been considered more stable than other polar ice sheets. But this new study suggests that once the melting and thinning process starts, it can accelerate quickly.