On October 1, Alaskan climber Balin Miller, 23, died when he accidentally rappelled off the end of his rope. Miller had just completed a roped solo climb of a route called The Sea of Dreams on El Capitan in Yosemite when he fell over 700m to his death.

News of Miller’s demise initially spread via a few climbers who were in Yosemite at the time, before the mainstream media picked up the story. They latched onto the fact that the young Alaskan’s climb was being livestreamed on the social media app TikTok.

The Metro newspaper in London crowed, “TikTok climber falls to his death at Yosemite during livestream while fans watched,” and the Daily Telegraph ran with “Climber livestreamed moment he fell to his death from Yosemite cliff.” Other outlets dubbed Miller an “influencer” and a “TikTok” climbing star.

Screenshot: www.independent.co.uk

The livestream

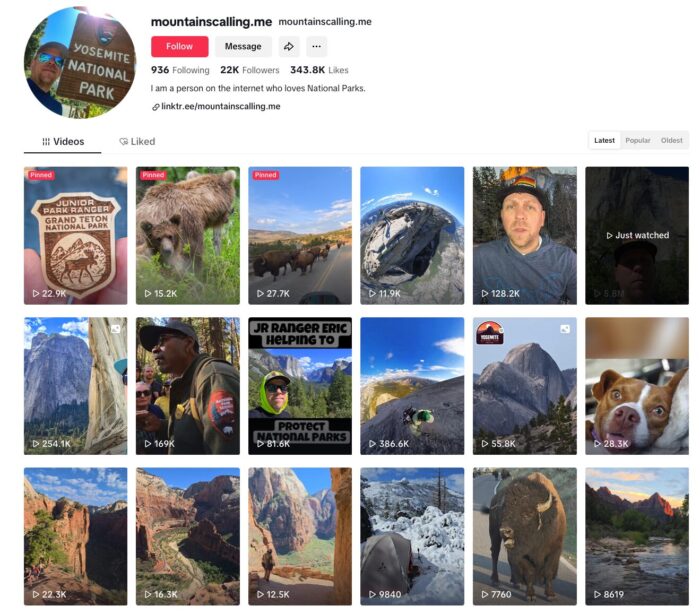

While the mainstream media often gets details of adventure news wrong, these headlines were particularly egregious since Miller was not livestreaming himself, nor was he a TikTok star. Instead, his death was livestreamed to hundreds of people by a TikTok account handle named @mountainscalling.me.

The account owner, who calls himself Eric (no surname), recently posted that he is a “Yosemite super fan” and that he was filming climbers using a long-range scope after attending an event in the park. As Eric did not know the climbers, he referred to them by the color of their clothing or equipment.

Miller became known as “Orange Tent Guy” to those who tuned in over the course of his multiple days on the route.

The TikTok account that inadvertently live-streamed Miller’s death.

In Eric’s post, he also stated that Miller was not involved in any of the livestreaming and that he believed Miller was not an influencer.

An accomplished alpinist

To anyone in the climbing world, this last statement came as no surprise. Miller was an accomplished alpinist from Anchorage, Alaska, known for his bold solo ascents and dedication to pure alpine style.

Four months before his death, he completed the first solo climb of Mount McKinley’s Slovak Direct, finishing the route in three days. Miller free soloed nearly the entire climb.

His achievement earned praise from top climbers, with Colin Haley calling it “super badass,” and Mark Twight reacting, “Holy shit.”

Balin Miller. Photo: Jeanine Girard-Moorman/AP

In the months before, Miller completed a string of solo climbs in Patagonia and the Canadian Rockies. In January, he climbed Californiana (5.10c; 700m) on Cerro Chalten, then moved on to solo Virtual Reality (WI6) and the demanding Reality Bath (VIII, WI5/6) in Canada.

What went wrong?

On October 1, viewers of Eric’s livestream watched Miller begin climbing around 10 am as he approached the final pitches of the route.

“We were all cheering for him and wanted to see him summit,” he said.

Near the top, around 1 pm, Miller’s haul bag became stuck lower on the pitch. Eric said that Miller went down to free it but accidentally rappelled off the end of his rope. Eric and Tom Evans, who had been taking photos of other climbers nearby, called 911, prompting a rescue operation.

Veteran El Capitan soloist Andy Kirkpatrick has climbed the same route and suggested that Miller’s fall could have resulted from a few small mistakes made at the very end of an exhausting climb. After finishing the final section of Sea of Dreams, Miller rappelled down to free his haul bags, which had become stuck on the wall below.

Balin Miller climbing in Hyalite Canyon. Photo: @balin.miller/Instagram

In the process, Kirkpatrick writes that he may have shortened his rope earlier when dealing with the complex rope system for both hauling his gear and climbing solo. When the bags jammed again and he descended to fix them, Miller likely assumed the rope was still long enough to reach.

Kirkpatrick suggests this was “the last thing he wanted to be doing so close to the top,” and that Miller was probably tired, relieved, and ready to be done. But as he rappelled, the end of the rope, hidden below an overhang, slipped through his belay device before he could react.

Does climbing have a social media problem?

After watching the video of Miller’s fall, copies of which sadly remain online, Andy Kirkpatrick wrote: “This film, these people, this world we live in — the virtual one — cheapens death, the loss of this young, amazing life recycled into nothing more than content, something to pass a few seconds before swiping onto something else in an otherwise spiritually empty day.”

In that context, it’s not surprising that some mainstream outlets, unfamiliar with the nuances of climbing and perhaps too eager for headlines, wrongly portrayed Miller as an “influencer” who live-streamed his own death. Yet they prompt a broader question for the climbing world: How does the pursuit of generating views and engagement shape the way risk and mortality are presented by some climbers?

YouTuber and elite rock climber Magnus Midtbo’s widely viewed and criticized solo climb of the Matterhorn with limited preparation and alpine experience, and free soloist Lincoln Knowles’s rage-baiting humor about falling, are just two recent examples of how some climbers use social media to amplify the drama of risk and drive engagement.

Miller’s death doesn’t fit into that trend, but it highlights how a culture that prizes dramatic online storytelling can be misinterpreted and how easily tragedy can be flattened into spectacle in the endless cycle of online content.