You’ve almost certainly owned an orchid at least once in your life. I used to keep mine on the windowsill, within reach of where I sit now. But a passing professor of botany happened to see it and, taking pity on the bedraggled thing, rescued it from my clutches. It is now thriving, safely out of my care.

It was impossible to tell from looking at the wilted thing, but a century of enthusiasts dedicated their lives, and sometimes lost them, hunting for orchids just like it. One of the strangest and most prolific was Benedikt Roezl.

If you like pictures of orchids, boy, do I have the article for you. Even better, you’re already reading it! Photo: Kew Gardens

From gardener to nobility

Benedikt Roezl was born in a village just outside Prague in 1824. His father was a gardener, and from a young age, it was clear that Benedikt would follow in his footsteps. At 12, Roezl became an apprentice in the gardens of the Bohemian nobleman, Count von Thun.

He must have been fairly good at it, because as the years wore on, he worked in increasingly high positions at some of the most important gardens in Europe. Baron Von Hugel in Vienna, Count Liechtenstein in Moravia, and Louis Van Houtte in Ghent all employed the young man in their greenhouses.

Soon, Roezl realized that greenhouses weren’t enough for him. Men like Van Houtte and Von Hugel had been explorers and plant hunters in their own right. Their celebrated gardens were a testament to years spent stalking the jungles, forests, and deserts of the Americas and Southeast Asia.

Roezl dreamed of visiting the tropics himself. In 1854, he made the leap and moved to Mexico. Once there, however, he didn’t charge into the jungle to begin collecting. Instead, he set up a nursery near Mexico City, selling European fruit trees.

Apparently, this didn’t fulfill Roezl either, so he bought a plantation to grow sugar, coffee, and tobacco. No sooner had he done so than he realized he was actually more interested in plant textiles. He introduced a bush from Southeast Asia and then invented a machine to extract its fibers. This invention would change his life, though perhaps not in the way he hoped.

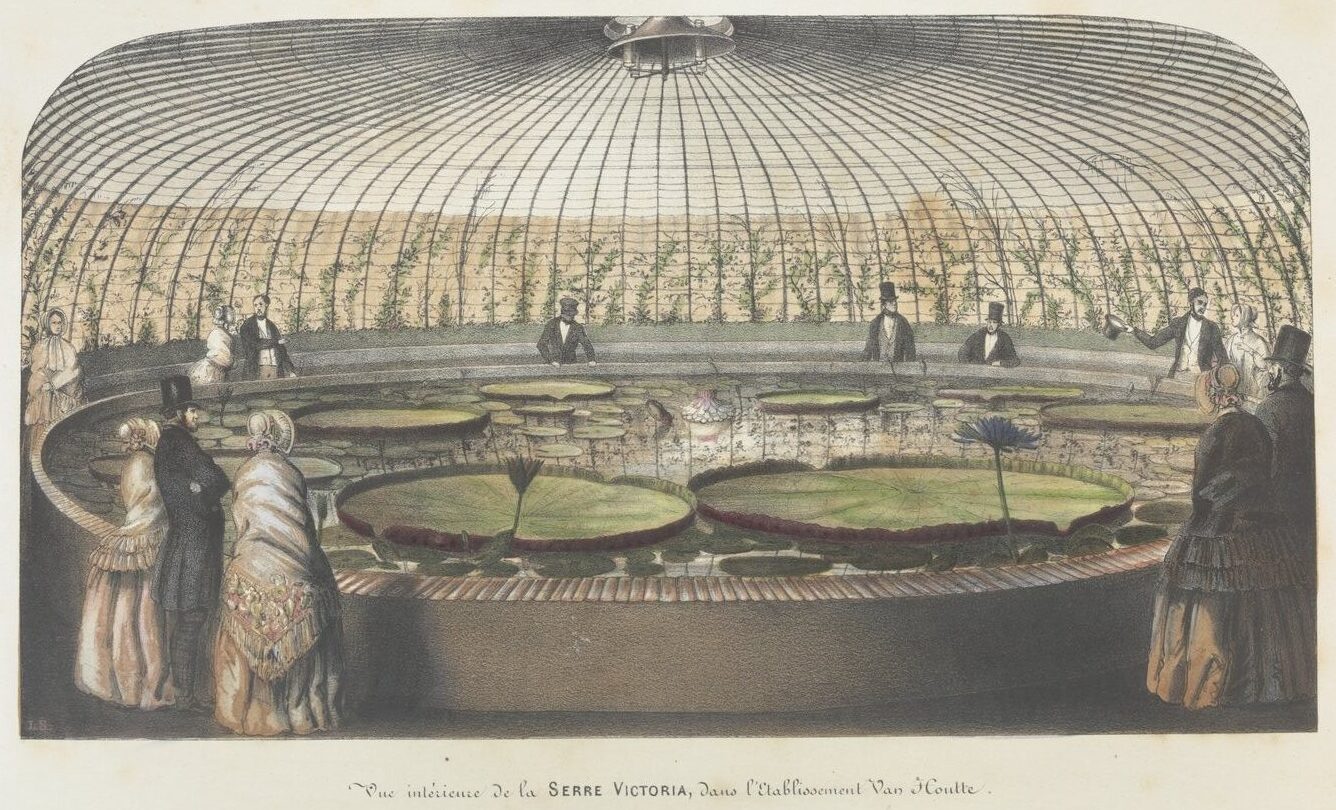

The interior of a greenhouse in Louis Van Houtte’s celebrated gardens. Photo: Archives Nationales

Another career change

In 1867, Roezl took out a patent in the U.S. for his machine to extract fibers from ramie, a plant in the nettle family that yields one of the strongest natural fibers. The agricultural sector was interested, so Roezl spent the better part of a year showing off his machine, which spun at sixty revolutions per second. He was in Havana, doing a demonstration, when his left hand became caught in the machine.

The grisly scene that followed certainly put off potential investors, but more than that, it left Roezl at a crossroads in his life. He was 44, one-handed, and half a world away from his native country. Naturally, he fitted himself out with an iron hook and shipped himself to the Sierra Nevada.

There, he collected and named Lilium columbianum, the Columbian Tiger Lily, and Lilium humboldtii, Humboldt’s lily. He sent them to Europe, where they achieved success as ornamental plants and likely gave him a taste of the celebrity a successful plant hunter could enjoy. He threw himself into the new career.

Roezl was a rapacious hunter, always on the move. He traveled through wild and unfamiliar territory at an alarming pace, sending back kilos of specimens as he went. During his first trip to South America, he covered over 3,000 kilometers in about six months, whirling furiously across Peru and Colombia.

Lilium Columbianum, left, and lilium humboldtii, right. Roezl named Humboldt’s lily after the German naturalist Alexander Von Humboldt, as Roezl had found the flower on the 100th anniversary of Humboldt’s birth. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Botanical treasures won and lost

Roezl collected anything he encountered, but orchids were his particular passion. After his first trip to Columbia, he sent back over 10,000 of them, as well as 500 other species. His shipments were measured in tons, with orchids of both known and unknown varieties making up the bulk.

The iron hook, whose necessity had sparked his life of plant collecting, was sometimes an asset. Roezl frequently met indigenous peoples with whom he had no shared language, and who were wary (history would argue, wisely) of strange white men. Roezl reported that the people he met were often charmed by the interesting, unusual object, and therefore more likely to a) not kill him and b) point him in the direction of whatever neat plants they happened to know of.

Not all the plants Roezl shipped off made it to their destinations. As I myself recently discovered, orchids in particular are fragile and demanding. One shipment of Roezl’s left Columbia with 27,000 living plants and arrived with only two.

Roezl certainly loved orchids, but it was a selfish and covetous love. Collection on the kind of scale he practiced left destruction in its wake.

In 1873, Roezl stopped by the Volcán de Colima in Mexico and offered local people 10 to 15 francs for every hundred orchids they brought him. He collected a total of 100,000 orchids, an astonishing amount. It would be impossible to collect so many so quickly in that area today, and historians of plant hunting have long wondered if Roezl may be the reason.

Most plants don’t do well on board 19th-century sailing vessels. Photo: Greenwich Maritime Museum

Misadventures of an orchid man

Unfortunately for Roezl, he was frequently robbed. Fortunately, he only ever had plants on him. On one occasion, a group of bandits captured him and were preparing to end his life. Upon discovering that all he had with him were plants, they concluded he was a madman. Killing the insane was thought to be bad luck, so they scampered off, one of them making the sign of the cross as he did so.

Roezl was robbed no less than 17 times. Though the dangerous areas he passed through accounted for many of these, he also seemed to be a little naive. While passing through Denver, he entrusted all of his money to a random Danish innkeeper, who promptly took the money and ran. He recovered quickly; within a year, he was sending 100,000 orchids by ship back to Europe.

By 1874, Roezl was burnt out. He’d spent five years traveling almost nonstop, introducing over 800 species previously unknown to science. While it hadn’t brought him vast wealth, he’d made enough to retire on. He spent his final years in a comfortable home outside Prague, dying in 1885.

Still widely known and celebrated for his collecting, the Kaiser attended his funeral. An International fund was created to raise money to build a statue in his honor, which still stands in Prague today.

His most appropriate legacy is in the plants he named. The International Plant Names Index lists 181 plants named by Roezl. Many orchid varieties, including Selenipedium roezlii, Sobralia roezlii, and Pescatorea roezlii, are named after him.

Left, Roezl’s gravestone. Right, a statue of Roezl in Prague, whose artist made a number of questionable choices. The sculptor gave him two hands for one, and included, strangely, a crouching indigenous man, presumably as some sort of sidekick. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

The orchid king

When Roezl sent hundreds of thousands of orchids and other plants back to Europe, they were going to one man in particular: Henry Frederick Conrad Sander of St. Albans, the “orchid king.”

Sander met Roezl in 1867 and was his agent in England afterward. To facilitate sales, Sander opened a seed shop and nursery that catered to those who wanted the best and newest — and were willing to pay. Sander also kept a massive warehouse close by the shop where Roezl’s mammoth shipments would be stored. While Roezl collected, Sander marketed and sold, to enormous success.

Roezl retired on his share, but Sander, a much younger man, was only getting started. He used the money from selling Roezl’s orchids to open a massive, four-acre nursery in St. Albans, dedicated to orchids.

Over the next two decades, Sanders sold over two million orchids and started an illustrated magazine dedicated to the flowers. The magazine, Reichenbachia, is now a valuable collector’s item, with a digitized version available through several libraries. His work became the cultural center of the orchid market, and it was all based on Roezl.

Left, an illustration from Reichenbachia depicting ‘Masdevallia chimaera’. Known today as the ‘Dracula chimaera’, this strange-looking orchid was originally discovered by Roezl in 1871 in New Granada (present-day Colombia and Panama). Right, a photo of ‘Dracula chimaera’. When Roezl sent in the first illustrations and description of the plant, Sander thought it might be some sort of joke. I can’t blame him.

The orchidomaniacs

While Roezl certainly seems singular, he was actually just a very flashy example of a certain type of guy that flourished in the 19th century. They dedicated themselves to the collection and exportation of rare flowering plants, especially orchids. Enthusiastic gardeners in Europe paid good money for rare and particularly eye-catching species, but for these orchidomaniacs, the money was only part of the motive.

There are tens of thousands of species of orchids, growing on every continent except Antarctica. To gentlemen of a botanical bent and an adventurous spirit, the urge to find and claim rare and undiscovered varieties possessed them, much the same way the need to acquire vast numbers of tabletop gaming cards possesses some people today.

Some of Roezl’s peers included William Arnold, who got into a duel with another orchid hunter and then drowned in Colombia’s Orinoco River while on the hunt. David Bowman and Gustavo Wallis both died of diseases they caught on the hunt, and Albert Millican was knifed to death by rivals. In 1901, out of a group of eight men searching for orchids in the Philippines, one was eaten by a tiger, another was immolated, and five more simply never returned.

The complexity and delicacy of the vast orchid family drove more than one prominent Victorian scientist to madness, though in this case it was temporary. In 1861, Charles Darwin, feeling poorly, wrote, “One lives only to make blunders. I am going to write a little Book for Murray on orchids & today I hate them worse than everything.”

Perhaps the remarkable thing about Benedikt Roezl, in conclusion, was not his exhaustive obsession with orchids but the fact that he managed to survive his obsession with orchids.