One reason for bouldering’s skyrocketing popularity is its low threshold of entry. When I think about the critical tools required, a list in an old guidebook comes to mind. In Texas Limestone Bouldering, Jeff Jackson provides the following “must-have” list:

- Rock

- Will

Most practitioners use a more complete kit. Jackson’s list, though, serves to emphasize one key point: Bouldering is rock climbing stripped to the bone.

By removing the overlay of ropes for safety or progress, boulderers can pursue climbing difficulty unencumbered. That said, a “boulder” often has to be a short section of rock — the safety threshold is relatively low when the only safety equipment is a pad on the ground.

As a result, bouldering grade scales fulfill the specific purpose of estimating how hard short climbing sequences are.

Their applied utility is broader. A boulder problem does not necessarily have to start on the ground and end a few metres above it. Most high-standard sport routes, for instance, contain at least one distinct boulder problem. The route may be 30 metres long, but the boulder problem (or “crux”) may only be five metres long. Accurately grading the route requires evaluating the difficulty of the crux or cruxes.

Jacopo Larcher on the crux of ‘Shikantaza’ in Valle dell’Orco. Photo: Jacopo Larcher

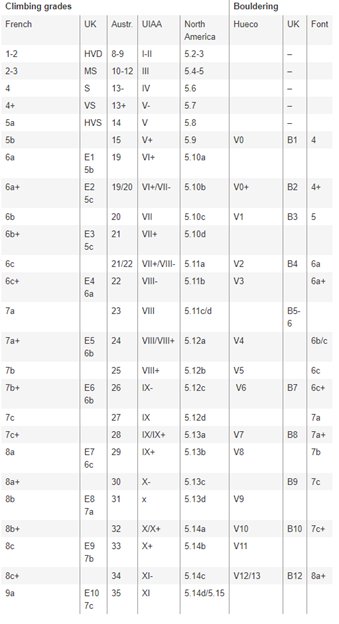

Climbers use one of two bouldering grade scales. The aptly-named Fontainebleau scale started in the de facto birthplace of bouldering. It’s older than the V scale, which John “Vermin” Sherman developed in Texas in the 1990s.

The two systems correspond to each other more or less directly. Worldwide, more climbers use the “Font” scale than the V scale, but many are familiar with both.

Bouldering difficulty starts at 1 (Font) or VB (V scale), and currently ends at 9A or V17. The difficulty is open-ended; two 9A/V17 problems currently exist in the world, and neither has been repeated.

Here’s how the two systems work, interact with each other, and fit into the broader context of rock climbing.

Fontainebleau scale (international)

Bouldering started in France’s Forest of Fontainebleau, so bouldering grade scales did, too. Climbers first developed the Font scale around the 1960s. The simple coefficients include a number, often a letter, and sometimes a + or -.

Most beginner climbers can reckon with a boulder problem graded 4 on the Font scale. An 8A+, on the other hand, requires the touch of an expert.

Note that the Fontainebleau bouldering scale looks similar to the French system for roped climbing difficulty, but the two systems do not correspond. 9A does not equal 9a. Often, the difference will be the capital vs. lower-case letter.

In context, Font 9A is the grade of the world’s two hardest boulder problems. French 9a is expert-level, but a long way behind sport climbing’s cutting edge.

Keep that in mind for later.

Hueco Tanks V scale (U.S.)

John “Vermin” Sherman started the V scale in the early days of bouldering at Hueco Tanks, Texas — the American mecca of the sport. Substantively, the “V” means nothing: it’s short for “Vermin,” who had a knack for publicity. The scale is simply a system of ascending numbers.

The rarely-used VB stands for V-beginner. From there, difficulty ranges from V0 to V17. Sometimes, climbers will add a + or – to indicate a boulder problem that seems to fall in between grades. But the vast majority of problems graded on the V scale settle to one concrete numeral.

Bouldering grades as crux difficulty in longer routes

Boulderers use the Font and V scales the most, but they’re not the only ones who do it. Roped climbers (most often sport climbers) commonly use bouldering grade scales to describe cruxes on routes.

Sometimes, the easiest way to think about a route’s crux is to isolate it. If it’s a sequence of five or eight hard moves, chances are it’s about the length of a boulder problem. In that case, it can be useful to describe the segment as a boulder problem and give it a grade on the Font or V scale.

Siebe Vahnee on the unrelenting crimps of Orbayu (8c). A hard sequence, or crux, can also be thought of as a boulder problem.

It’s common to hear a sport climber talk about a given route in segments. Typically, you would hear or read something like “the route starts with 10 metres of 7b climbing. Then you do a six-move boulder problem that’s probably 7B. After that, there are another 15 metres of sustained 7c.”

The above route has a distinct crux: Font 7B climbing is solidly harder than anything you would find on a route graded French 7c. Therefore, the climber grading the route must reconcile the hard crux with the otherwise more moderate climbing to land on a French grade that makes sense. In this case, the route might settle at French 8a/+.

A final point: in some cases, bouldering grades correspond directly to route grades. A 7B (or V8) crux could mean that the route is 8a (or 5.13b). However, that’s usually only true of short routes. Long routes with multiple cruxes and sustained climbing between cruxes often require more consideration.