A pair of Japanese data scientists have published a paper exploring whether artificial intelligence (AI) can predict mountaineering accidents.

The paper’s senior author, Dr. Yusuke Fukazawa, claims that their model gives climbers “a better understanding of the risks associated with their planned actions, enabling safer decision-making and preparation.”

Fukazawa adds that by tailoring risk assessments to each climber’s unique situation, “our model offers personalized safety recommendations…instead of the traditional, one-size-fits-all warnings.” The paper appeared in the International Journal of Data Science and Analytics.

To the casual reader and mountain enthusiast, these snippets from the press release will mean very little, so we’ve dug deeper into the paper to give you a clearer perspective.

Dr. Yusuke Fukazawa. Photo: Sophia University Japan

What did they do?

Authors Sato and Fukazawa argue that most previous research has relied on surveys and accident data to explain why a mountain incident happened. These used details like the climber’s personal characteristics, the equipment they carried, and the terrain where the accident took place.

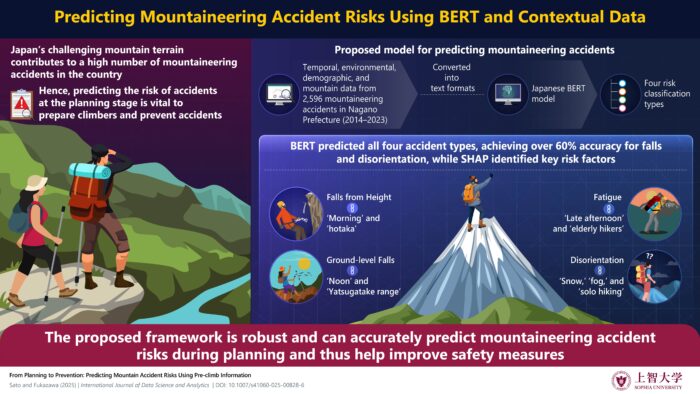

Instead, these authors focused on predicting the type of accident a climber or hiker might face using only the information available before a trip.

They considered four categories of accidents: falls from a height, falls on flat or gentle slopes, fatigue-related incidents, and cases of becoming lost or disoriented.

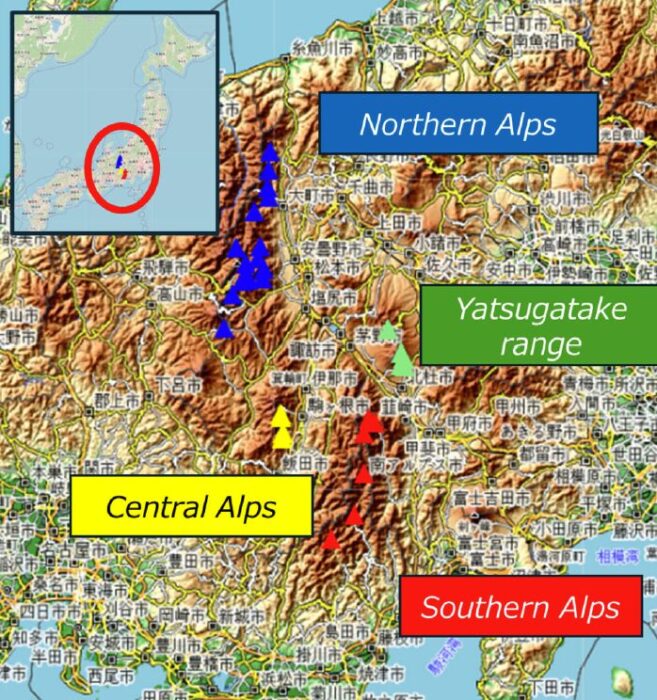

The mountain regions of Nagano prefecture. Photo: Sato/Fukazawa, Sophia University

Using records from 2,596 mountain accidents in Nagano Prefecture, Japan, between 2014 and 2023, they extracted data such as the date, season, time of day of each incident, weather, the hiker/climber’s demographic information (sex, age group, party size). They matched this up with information about the mountains sourced from Wikipedia pages, including terms like “ridgeline,” “snow,” and “famous peak.”

Sato and Fukazawa then converted these details into short, structured sentences. For example: “December 15, 2019, winter, around noon at 11:00, weather: clear. Male, middle-aged, 40s, party of 4. Northern Alps, Mt. Nishihotaka, features ridges and ridgelines.”

A range of particular AI methods were then used to see which could most accurately predict the type of accident from this “planning-stage” text data.

What were the findings?

The best results came from the Japanese BERT model (a type of AI language model), which correctly estimated the type of accident in about 57% of the accident cases. The model was also able to highlight which words were most linked to each type of accident. For example:

- Falls from height: “morning,” “Hotaka” (a steep peak)

- Ground-level falls: “noon,” “Yatsugatake range”

- Fatigue: “late afternoon/evening,” “older”

- Disorientation: “snow,” “fog,” “night,” “solo”

Photo: Yusuke Fukazawa/Sophia University

The analysis comes with some real-world caveats, though. The model was fed actual weather conditions from the accident reports, information a climber or hiker wouldn’t know before heading out, so its performance could differ when using forecasts.

Some mountain descriptions pulled from Wikipedia (which weren’t presented in the paper) could have included phrases like “steep and dangerous ridge,” which might have given the model clues too close to the actual accident outcome.

The data set also covered only accidents, not the countless safe days out in the mountains, so it can’t tell whether a factor truly raises risk or just reflects where people like to go.

In addition, the model was also never challenged with different time periods or mountain regions.

What’s the take-home message?

Put simply, the study suggests that with the right planning details, such as the date, route, group size, weather forecast, and basic information on the mountain, an AI model can identify patterns linked to different types of mountain accidents.

The premise becomes less abstract when you imagine it embedded in a hiking app. Sato and Fukazawa propose that if the AI model detected a high risk for a specific type of accident, the app could respond with tailored advice, such as checking gear, adjusting the route, or rethinking the timing.

Photo: Shutterstock

In practice, such a system could run quietly in the background, analyzing a hiker’s plans alongside forecasts and trail data, then flagging risks for situations like disorientation on a solo hike in poor weather, or fatigue on a long afternoon ridge walk in the heat. Timely prompts delivered via an app could encourage hikers and climbers to start earlier, pick an easier route, or carry extra food or gear.

While experienced mountain goers may scoff at the idea of relying on AI technology, the 2024 survey of 764 Pacific Crest Trail hikers reported that 99.2% used an app for route planning and navigation.

For now, though, these AI models remain an interesting concept rather than a proven safety measure. Without further development on larger datasets in different countries, and later real-world testing with app integration, it would be premature to conclude that this sort of AI model can reduce the risk of accidents in the mountains.