On September 4, a six-strong team of mostly Canadian paddlers brought their canoes ashore in Waskaganish, a Cree community on James Bay. They had completed a 1,200km journey that began three months earlier in Tadoussac, Quebec, where the Saguenay River meets the St Lawrence.

Their route traced a line across lakes, rivers, and portages that once formed a vital artery of the fur trade, linking the Gulf of St. Lawrence to the shores of the Arctic Ocean.

The 97-day expedition, led by 33-year-old guide, writer, and adventurer Bruno Forest of Tadoussac, started on May 31.

“When I left for this expedition, I left my home by walking,” Forest recalled. “I went to the beach, and then we left for 1,200km. I didn’t have to take a car, it was directly into the canoes. This project was a mix between a passion for history and a passion for adventure, the outdoors, and canoeing.”

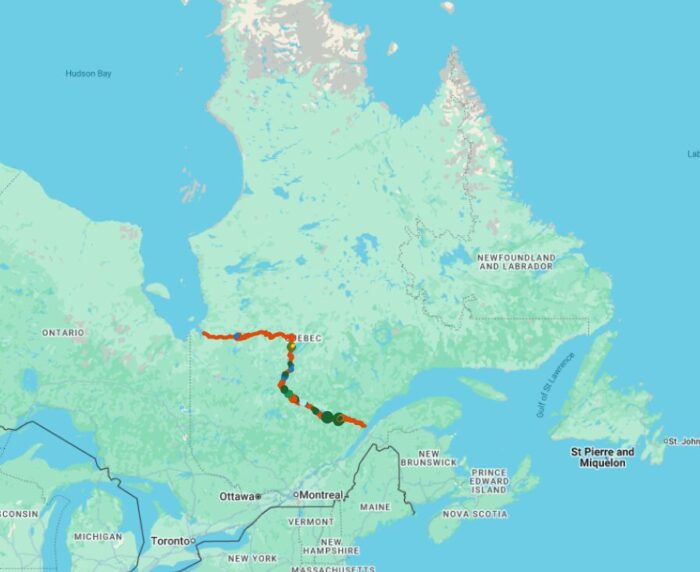

The 1,200km route. Edited map: À la Mer du Nord

Following those before them

Long before the French fur traders pushed west, these rivers were highways for Indigenous nations such as the Innu, Cree, and Atikamekw. They trapped and hunted on their ancestral lands, then gathered at the watershed divides to trade goods such as beaver pelts, shells, stone, and later, European tools.

The team often cooked on open fires along the route. Photo: À la Mer du Nord

“There was already a big trading system,” Forest explained. “It was accentuated when the Europeans arrived with merchandise that the natives appreciated…and eventually some explorers in the 17th century, like Father Charles Albanel and Louis Jolliet, went all the way to Hudson Bay.”

The route north

In the first weeks, the team paddled along the Saguenay River and into Lac Saint-Jean, a large lake that acts as a gateway to the north. This section is dotted with towns and fishing cottages, providing opportunities for the team to resupply and visit local communities. But beyond Lac Saint-Jean, the expedition entered wilder country.

From the lake, they pressed northwest into waters flowing toward Chibougamau, a large town in northern Quebec. Here, the challenge intensified. The team had to battle upstream, often unable to paddle at all.

“We were literally climbing a mountain in terms of altitude, going upstream on rivers with a big flow of water,” Forest explained. “We were mostly walking in the river on rocks…sometimes going up rapids just hauling our canoe.”

The team arrives in Chibougamau. Photo: À la Mer du Nord

Portages were hard. Trails that once served traders had long been reclaimed by the forest, so the paddlers often had to hack their own.

“Sometimes we would recognize the old traces of the portage that was now taken back by forest,” Forest said. “And then we would pass with axes, with saws, and create a new portage, sometimes for two kilometers, cutting all the trees so the canoes could pass on our heads.”

The rivers were swollen from summer rain, and the hard work continued, with the team pushing upstream for the first half of the route. Eventually, they reached the height of land, a watershed divide that First Nations used for centuries as a meeting point to trade. From this point, rivers began to flow north toward James Bay, and the character of the journey changed.

Liberation

“When we started to go downstream, something liberated in us, and we were suddenly having fun. It was not easy, but it was a more human, accessible travel, more comfortable.”

Some of the terrain the team covered in the Albanel Mistassini Waconichi Wildlife Reserve, a huge territory of lakes, rivers, and wild landscapes. Photo: À la Mer du Nord

The descent carried them through Lac Mistassini, the largest natural freshwater lake in Quebec. The lake is notorious for its winds, and local Cree had warned them of its dangers.

“On that lake, it’s a big deal. You can’t go if there’s wind,” Forest explained. “There’s an island they call Manitouk. They told us you should never point at that island because the wind will rise and be very bad with you.”

However, Forest and his team had no issues, paddling 50km in a day as they crossed the lake in calm conditions.

From Mistassini, the canoes followed rivers north and west into Cree territory until finally reaching the salt waters of James Bay. At various stops, the team discussed the region’s history with local families.

“They recognized some parts of their history in our travel, and it helped so many stories emerge,” Forest said. “We met a lady named Jane Voyageur, whose great-great-grandfather was a voyageur [early French and French Canadian fur traders] for the Hudson’s Bay Company.”

Reviving Tremblay Canoes

One of the most interesting aspects of the expedition was the team’s choice of boats. Instead of modern Kevlar or fiberglass, the team paddled cedar and canvas canoes built in the style of the Tremblay Canoes of Saint-Félicien, on Lac Saint-Jean.

Founded in 1914, the Tremblay company supplied working canoes for prospectors, hunters, and northern Indigenous communities until its closure in 1981. They were, in Forest’s words, “the last canoes of the fur trade route.”

Determined to honour that tradition, Forest tracked down five surviving Tremblay artisans now in their eighties and nineties and interviewed them about their craft. He even wrote and published a book about the company’s history to prove his seriousness to them. That effort persuaded one craftsman to reopen his old workshop.

A former Tremblay craftsman with the canoes in production. Photo: À la Mer du Nord

“I asked him, would you accept building canoes again for this great expedition that we planned? And he accepted,” Forest recalled. “I took care of finding the materials and the wood, and he cleaned his workshop. I was his helper all last summer, and he taught me how to build the canoes. We made five, and repaired an old one, so we had six in all.”

The finished canoes. Photo: À la Mer du Nord

The cedar and canvas canoes proved both resilient and fragile. Their wooden frames flexed through rapids, but the canvas skins needed nightly patching with tape. “Sometimes we took on so much water that the canoe was full, and we were just floating in it. [But] in some ways, they were the best canoes I’ve ever used.”

An Innu connection

Ten paddlers set out on the expedition, ranging in age from 21 to 62. The plan was for eight of them to complete the full distance, while two joined as ambassadors from the Innu community for the opening stretch. In the end, six paddlers — three women and three men, all Canadian except for one from France — reached Waskaganish. Three others withdrew along the way because of physical difficulties, including a back injury.

Francis Bossum, from the Innu Nation of Mashteuiatsh, only joined as an ambassador for the opening week, alongside his father, Stacy. But the young paddler quickly decided he wanted to continue.

Stacy and Francis Bossum, right. Photo: À la Mer du Nord

“During the week, Francis [Bossum] decided that he would like to stay with us, and we were very enthusiastic about it. He was a very good paddler and a good companion,” Forest recalled.

Bosum’s presence lent the expedition more than just muscle. As an Innu, his participation was a reminder that these routes predate European contact, that they were first and foremost Indigenous pathways.

After the journey

“When we arrived, everybody cried,” Forest said of the final landing in Waskaganish after the 97-day journey. “It was so strong, what we lived together. It was very intense.”

The six paddlers received matching tattoos while visiting Mistissini, a Cree community in northern Quebec. Photo: À la Mer du Nord

Plans are now underway for a documentary film, public events, and a book. For Forest, the goal is not only to document a feat of endurance, but to honor the memory of those who came before on these historic fur trading routes.