The Ecuadorian admits that she only begins to struggle on no-O2 climbs above 8,300m — which is why she wants to do all five peaks above that altitude.

Last week, Carla Perez climbed a different Makalu from most people. Hers was 8,463m. That is the mountain’s actual altitude, only reachable without supplementary oxygen. As she knows from experience, the altitude counter stops the moment the bottled oxygen starts flowing. If you turn it on at 6,000m, that is the height of the mountain you climb.

Raised on the outskirts of the Andes, Carla Perez is currently one of the strongest female Himalayan climbers, according to guides and fellow alpinists. She spoke to ExplorersWeb about her climbs, projects, mountain ethics, and the power of love and friendship in the thin air.

“I’ll try to be objective, but I will probably get driven by feelings, as I always do,” she warned.

Makalu’s strength test

How hard was it to turn back during your first summit bid, then find the strength and motivation to try again?

It was hard, obviously. But several factors were clear, starting with the weather. The most difficult thing is to know when to take that decision, to avoid serious consequences. You only know that from experience. It wasn’t that I was already freezing or exhausted, which did happen to me on my first Everest attempt. It was that previous experience that helped me to decide to turn around.

Soul mates: Carla Perez with Pemba Sherpa and Topo Mena (in red).

It must have been frustrating to see so many climbers heading down with the summit under their belts while you stayed in BC hoping for another window to open.

These days, most mountaineers go with huge support: O2, fixed ropes (which I also used), help pitching and supplying camps. All this support makes things happen very fast. And if you go without O2, you need more time, you need to climb as people climbed 20 years ago. That means three things: patience, a good strategy, and enough physical strength. I can’t just show up in Base Camp and go up. Don’t let yourself be tempted to hurry or feel down because others are summiting and going home. This is not a criticism of others choosing to climb in different ways. It is just that this is not my way.

What was your strategy for the second summit push?

The strategy includes choosing the right moment to begin the push, who to climb with, and the conditions.

So I was strong, patient, and ready for a second try. In addition, my partner Topito [meaning little mole – he gained that nickname after the glasses he always wears because he’s so shortsighted] said he would return from Kathmandu to climb with me. Also Pemba, a very dear friend of mine, said that he would really like to try and climb an 8,000’er without O2 and that he would come if he had time after guiding on Everest. And so they came – it was awesome! Pemba’s support was important. He didn’t do it for work or money, just for friendship. He’s a brother to me. How could I not be motivated? [Note that Pemba finally decided to use oxygen beginning at Camp 4.]

Summit at last: Pemba Sherpa, Carla Perez, and Topo Mena.

The summit push

What was the weather like on the second attempt?

Well, the weather this season has been great for oxygen-supported climbers, but not ideal for no-O2 ascents. Winds were 30 to 50kph. That’s okay with gas but really hard without. To me, 25kph is the limit. Yet there were some windows through the season: May 5, April 12, April 15, April 21, and the short one on April 24. The game is to be ready, acclimatized, rested, and with your things packed when the window opens. My mistake on the first attempt was to go for April 12 instead of April 15, as meteorologist Vitor Baia had recommended. But thanks to that mistake, I was later able to climb with Topo and Pemba. I can only be grateful for that experience. As for the climb itself, we had 16 hours of good weather. The rest was strong winds and heavy snow, just as Baia had forecast.

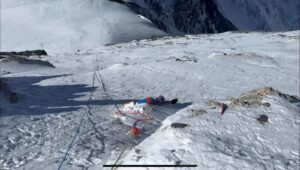

Dealing with seracs and mist on Makalu.

Beyond the “wall”

Why are you focused on climbing the highest five 8,000’ers without O2? Why not the rest? After all, you’ve climbed Cho Oyu and Manaslu no-O2 as well.

True, I did those two, and attempted Broad Peak, but these were all preparation. They were a chance to learn about my body and get ready for Everest. After climbing Everest without O2, I noticed something interesting that happens to me. I can’t tell whether other people are the same but it works this way with me. Below 8,300m, I am fine, clear-minded, and good. But at 8,300m, there is like a wall, beyond which the going gets extremely hard. I can’t keep warm, lactic acid accumulates and doesn’t go away, and my mind blurs. I get so vulnerable, and being vulnerable makes you grow as a human being. So that’s it. I want to experience what really challenges me, and the challenge is on the five peaks that surpass 8,300m.

The final steps before the summit of Makalu.

Everest with and without O2

How different is it to climb above 8,300m with or without O2?

I can speak from experience since I climbed Everest both without oxygen and then with oxygen when guiding for Alpenglow last year. The difference is HUGE. It’s more than a difference in fact. I believe that when you start using O2, that is as high as you ever get. I mean, if you start with O2 at 6,500m, that is what you have climbed: a 6,500m mountain.

Oxygen is something INCREDIBLE. First, it warms you immediately. In my case, I was never cold when on O2. Second, you don’t feel lactic acid accumulating in your muscles. You push, and the muscles work, they are not overloaded. Third, your mind is clear, you are well-coordinated, you think properly. On Everest [North Side], I used O2 from Camp 1 at 7,100m. The most difficult part of the entire climb was just reaching that point.

Fourth, it boosts O2 saturation immediately. On Makalu this spring, Topo climbed without oxygen until 7,500m, and his blood oxygen level sat at 75-78%. When he put on the mask and switched the flow to 1L/minute, his oxygen saturation rose to 97%.

The sun goes down from high on Makalu.

Uphill on a bicycle vs a scooter

So climbing with supplementary O2 is not really climbing?

Climbing with O2 is something you do for fun: to enjoy the landscape, the surroundings, the atmosphere…But from a sporting point of view, an O2 climb is not valid. In my experience, switching to O2 is like entering a hyperbaric chamber. You get younger, stronger, more powerful. Without O2, you are literally dying. You don’t eliminate lactic acid, your blood thickens and cannot circulate properly, you’re cold and confused, you suffer from ataxia, you must be extremely careful when changing your jumar from one rope to another not to do something really dangerous…It’s like facing a tough uphill with a bicycle or with a scooter.

Using O2 is fine, but don’t ever say it is “almost the same”. One has nothing to do with the other. Some of the strongest climbers in history understood the difference. Ueli Steck needed three attempts to do Everest without oxygen. Kilian Jornet, one of the climbers I most admire, came down completely exhausted and confused. David Goettler, who is a machine… they all saw how different it is.

My advice is, to go and try. Not on a lower 8,000’er, which is relatively easy to climb without O2 if you are very fit. Try one of the bigger ones with oxygen and then without, to experience the difference.

Natural adaptation to altitude?

You were born in Quito, at 2,800m above sea level, and climb often in the Andes. Do you think that you might have a natural adaptation to altitude?

My house is at 2,600m above sea level and my parents live at 3,000m. I think that may indeed have a positive impact on how I adapt to altitude, but there is a point at which we all reach our limit of acclimatization, and the suffering is the same. Every time my mum, for instance, reaches 4,500m or above, she starts bleeding from the nose and her ears feel like they are about to burst. So I can’t really tell how these adaptation processes work.

The fact is, though, that no-O2 climbs are becoming less and less popular, especially with younger climbers. Do you think there should be some limit?

One of the most wonderful things about this sport is the freedom it provides to choose your own rules. I can choose to go without O2 or without using the fixed ropes, but everyone decides what the rules of their game are. Anything that makes you dream and enjoy. I accept all the options available. I don’t believe I should lecture others on how things should be, either on the mountain or in their personal lives. But I know which I prefer.

During Perez’s no-O2 climb of Makalu.

I was inspired by Ivan Vallejo’s [Ecuador’s first 14×8000’er summiter] documentaries, in which classic-style expeditions involved climbing without supplementary O2, using little support, and enjoying the wisdom that the mountain provides. That is what really called me.

Guiding on Everest

What was it like to guide on Everest?

It was an amazing experience because I was hired as an assistant guide. That meant doing part of the work of the Sherpas: fixing ropes, carrying loads. And that established deep bonds of friendship with the Alpenglow staff. It was revealing. I feel that society tends to separate Sherpas and Westerners. Segregated, separated, as if we could never establish equal bonds of friendship. But Pemba is my friend, my climbing partner, my bro. Why is it all about “the Nepalis did this”, “the Westerners did that”? Why can’t we just climb together?

Topo Mena’s atop Makalu. It was his second ascent of the season, and first without O2.

In addition to Pemba, you also climb with your life partner, Topo Mena. Does your relationship make the climbs easier or more difficult?

Before being partners in life, Topo and I were very good friends and climbed together. We climbed Aconcagua’s South Face. So our relationship has grown out of our respect and passion for the mountains, and for each others’ mountain dreams. When we start a climb, we do our best to leave behind our sometimes clashing emotions. That is essential. The mountain is a temple for both of us. We used to fight more when we started climbing, but we’ve grown together. We need to forget about “I” and become “we”, ready to give our best for the common goal. Same with our other mountain partners.

Not interested in speed

What’s next — Kangchenjunga or Lhotse? Maybe something else?

Yeah, I know Kangchenjunga and Lhotse are part of the project, but I can’t really tell when I will go. I am a bit tired of high altitude. Climbing without O2 is extremely hard and also time-consuming. I miss doing more rock climbing, paragliding, technical routes… and of course, I want to finish my training as IFGMA guide. I have only two exams left.

As for the lower 8,000’ers, time will tell. I’d like to try a different route than normal on some of them. A new route would be a dream, of course. One of the people I most admire is Elisabeth Revol and her attempt on Nanga Parbat. But I also have my limits and I have to accept them and stay within. There is no need to do something beyond your limits if it jeopardizes not only your life but also your partners’.

Otherwise, I am not interested in completing the 14×8,000’ers. And I am definitely not in a hurry.