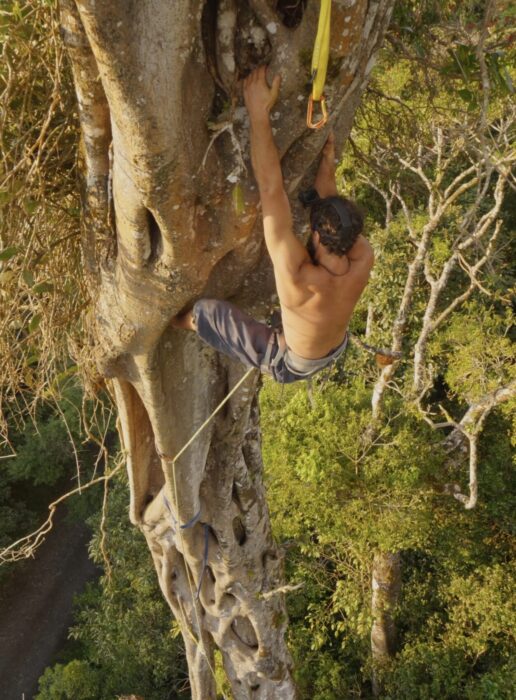

Most climbers learn on rock or at the gym, but 26-year-old American Noah Kane started with trees in Costa Rica, where he spent much of his childhood. He did not climb up the branches as a curious kid would, nor use the rope techniques of an arborist or canopy scientist. He climbed a tree like a rock climber.

After dropping out of film school, Kane, then 19, decided to head back to Costa Rica and the Monteverde Cloud Forest, where he reconnected with old friends Rafi Vargas and Izzy Moore and started climbing.

“This is where climbing actually started for me,” explained Kane. “I was like, ‘Oh, here are these old friends of mine. They’re doing this thing called climbing.’ ” He added that at the time, “They didn’t even really know that rock climbing really existed.”

Now six years later, Kane and his friends have pioneered climbing on strangler fig trees in Costa Rica and released a widely viewed documentary on this esoteric but wonderfully different type of climbing.

Strangler figs

Kane and his pals aren’t climbing any old tree, such as backyard conifers or maple trees. “The type of tree that we’re climbing is called a Strangler fig. It basically is a type of tree that starts out by growing on top of another tree.”

The Strangler fig begins life high in the rainforest canopy. “It gets pooped out by a monkey or a bird in the canopy, grows, and sort of starts its life as an epiphyte [a plant that grows on another plant but is not parasitic].”

Photo: Noah Kane

“It gets out its nutrients from the clouds and arboreal soil up there, grows its roots down to the main soil, gets access to all that superfood of nutrients, and then just grows a crazy trunk around the existing tree,” he said.

He explained that this process gives the tree its name. “So it gets the name Strangler fig because people thought that it strangles the existing tree. There’s actually some interesting evidence that maybe it doesn’t expedite the death of the other tree. It just uses it for support.”

Perfect for climbing

In the cloud forest, Kane and his partners climb mainly on private land during the dry season, from January to May. Cloud forests occur in high mountain regions where clouds and mist linger year-round. The constant moisture creates a cool, humid environment that supports a wide diversity of plant and animal life.

They climb barefoot to minimize damage. “We’re climbing barefoot, mostly out of an ethic of trying to protect the tree as much as possible,” Kane said.

Monteverde Cloud Forest Reserve is a lush, biodiverse protected area in Costa Rica, known for its cloud-covered forest. Photo: Shutterstock

He notes that the approach also toughens their feet over time. “I’m sure you could devise some sort of, like, leather moccasin that could also work, but once you climb quite a bit on the trees, you really get these tough calluses,” he added.

Strangler figs don’t have a solid trunk but rather a lattice of vines fused together into what Kane called “really strong wood.” Even vines as thin as a bicycle handlebar can hold his weight.

Natural protection

“The easier tree, you know, it will have more handlebars you can wrap your arms around, your fingers around. And so we’re wrapping slings around those full-on handlebar sections of the trunk. Sometimes they’re really easy to access. Sometimes, they’re kind of connecting against the old tree.”

“You’ve really got to kind of shove the sling in and work it out,” he said, describing how they protect their climbs using natural anchors such as slings or knotted rope known as a monkey’s fist, instead of metal hardware.

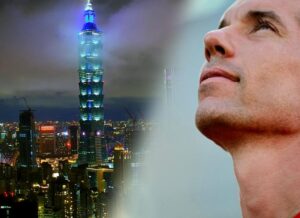

Photo: Noah Kane

“It kind of feels like traditional rock climbing, in the sense that you’re using the natural protection of the tree,” Kane explained. “We’re certainly not drilling in bolts or adding any other gear, but it also has this kind of sport climbing feel, in that it feels pretty safe once you get that protection.”

He added that the trees’ dense wood makes falls less risky than they might sound. “If you’re protecting anything really bigger than your wrist, it’s pretty much going to hold a fall…It’s really confidence-inspiring. And we’ve taken some big falls.”

Overhangs

Watching Kane’s videos, it’s clear this isn’t delicate climbing. He likens it more to muscular crack and off-width climbing. “Probably my strongest experience with a tree was on a tree called the porcupine tree, and it’s featured in loads of my films,” says Kane, now a filmmaker despite dropping out of film school.

“It has the really iconic seven-meter layback, so you’re sort of pulling on a pinchy tufa structure, putting your feet just on vertical bark, pretty much pulling and pushing as hard as you can. And that’s just sort of one of the most iconic sort of individual portions of tree climbing that we’ve ever found.”

An overhanging Strangler fig. Photo: Shutterstock

Some of the trees even go beyond vertical and overhang significantly, thanks to the unique way in which Strangler figs wrap around their hosts. Kane doesn’t tend to grade the climbs in traditional rock climbing standards, but has a sense of how they compare to grades on rock.

High in the canopy

Most of the Strangler figs that Kane climbs are doable in a single rope length, with few trees stretching higher than 40m. Though the trees naturally thin out towards the canopy, the lattice-like structure of the Strangler figs provides a lot of stability, so when the wind blows, the structure twists rather than sways violently.

He once spent a night high up in the canopy in a tent rigged up across branches, as the tree contorted itself beneath him throughout the night.

While Strangler figs exist in other parts of the world, Kane is happy focusing on Costa Rica for now. He’s wary of encouraging too much activity in a sensitive rainforest, but he has held a few low-key tree-climbing festivals, and occasionally collaborates with professional climbers.

“I think it’s super cool, super fun and and I hope that if folks are really interested in coming down and trying it. We’re usually pretty open to taking people out.”