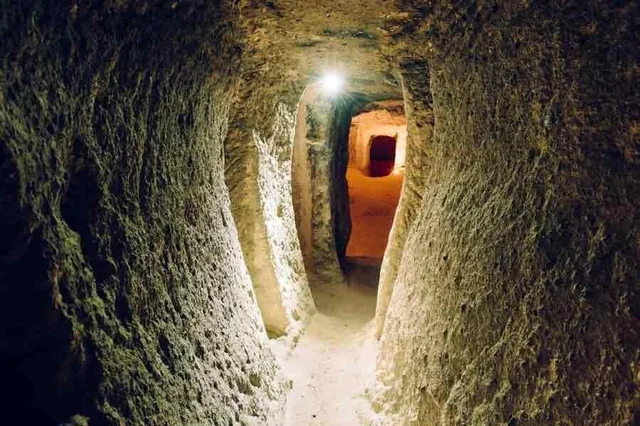

Walking along the boundaries of her farm in the Bavarian countryside, Beate Greithanner was shocked when one of her cows fell through a gaping hole in the earth. Hidden under thick shrubs and bushes, a series of strange tunnels ran through her land. Extremely narrow, with odd features, these so-called erdstall tunnels continue to baffle scientists.

Erdstall is German for “earth stable” or “earth place.” Other sources give the tunnels a mystical bent, calling them mandrake caves, goblin holes, or dwarven holes. The tunnels are extremely tight, one meter high and 60cm wide, with little oxygen. There is only one way in and out, no back doors or exits.

There are vertical or horizontal holes called schlupfs, which are slip-out passages measuring 30 to 40cm wide and 40 to 50cm tall. The schlupfs connect various levels of the tunnels, which can go on for 50m. There are also stair-like and bench-like features.

A young boy in a slip passage. Photo: Unknown

There are four main categories of these tunnels. Type A is long and horizontal, with a couple of slipouts and gentle downward slopes. Type Bs are more complex, with a multi-layered system, vertical slip passages, nooks, and possible seating areas. Type C are more spacious and have horizontal slipouts. Type D tunnels contain larger interconnected chambers.

There are 2,000 erdstalls in central Europe, including 700 in Bavaria and 500 in Austria. Typically, they are located in rural areas near historic settlements, often adjacent to old churches, cemeteries, and forests with gentle slopes or minor hills. Though many European countries have underground tunnel systems with their own unique stories, they look nothing like the erdstalls.

Discovery

In 1878, a Benedictine priest named Lambert Karner heard rumors about tunnels scattered through Lower Austria. Some farmers had found the entrances while plowing their fields.

Near Guglitz, Karner explored his first erdstall. Over the next 30 years, he studied over 400 in the region. He surveyed and documented each by candlelight, describing them as “strange winding passages where one can often only force oneself like a worm.”

Karner wrote a comprehensive work on the tunnels and their potential purpose, titled Artificial Caves in Old Times (1903). The work does not have an English translation, and so the erdstalls remain little known.

Josef Weichenberger in a horizontal slip passage. Photo: Josef Weichenberger

Few written sources mention erdstalls, and those that do fail to describe their purpose. A 13th-century Austrian poet named Seifried Helbling called the secret tunnels a sloufluoc, which refers to a hiding place for families during raids.

Research

In the 2000s, erdstalls made the news when dairy farmer Beate Greithanner found one on her property.

“The cow was grazing. Suddenly she fell in, up to her hips,” Greithanner told the press.

She called for her husband, Rudi, who decided to crawl into the claustrophobic space, hoping to find treasure. He found no treasure, only darkness and thin air.

They invited a team of geologists to the site, some of whom were members of a niche research group called the Working Group for Erdstall Research, led by Dieter Ahlborn. Dieter and a colleague went into the tunnel, which was only 70cm high. Dieter’s colleague, Andreas, cut his journey short due to a lack of oxygen, while Dieter continued until he found a piece of wood. Radiocarbon dating placed the wood between 950 CE and 1100 CE.

Exploration of more erdstalls in the region brought forth bits of charcoal or ceramic shards of the same age. However, investigators found most tunnels “swept clean” of any human presence.

A hideout?

Because of their proximity to human settlements, some people believe erdstalls were refuges for villagers during times of war or escape routes from villages.

Erdstall researcher Josef Weichenberger supported this theory and believed the tunnels were constructed as a temporary hiding place. The 11th to 13th centuries were called the “clearing period.” Bavarian farmers traveled down the Danube to find farmland further east, where they encountered Hungarian tribes. Weichenberger thinks they dug the tunnels as temporary hiding spaces during Hungarian raids.

He tested his theory by staying in an erdstall for 48 hours. The lack of oxygen eventually started to affect him and a colleague, but when they moved to a different section of the tunnel that was more spacious, they could breathe more easily.

Slip passage. Photo: Birgit Symader/Historiches Lexikon Bayerns

However, in an online article from Der Spiegel, spelunker Edith Bednarik challenged this theory. Bednarik says the tunnels don’t have proper ventilation and are too small to house groups of people. The slip passages can barely fit an average-sized adult. There’s also no back end and just one entrance/exit. A fire or flood would be fatal.

If it wasn’t a hiding place, perhaps it was used for food storage? The erdstalls are perfect for keeping food fresh and cold; perhaps medieval people turned them into ice houses, placing big blocks of ice into the depths. Yet, researchers have found no remnants of food or animal products.

Older than we think?

Dr. Heinrich Kusch, an archaeologist from Germany, does not think these tunnels were medieval at all. He thinks they are much older. He believes that people built the tunnels during the Neolithic period. He states:

Across Europe, there were thousands of these tunnels-from the north in Scotland down to the Mediterranean. They are interspersed with nooks; at some places it’s larger, and there is seating, or storage chambers and rooms. They do not all link up, but taken together, it is a massive underground network.

Of course, any weird phenomenon draws believers in the supernatural, and some think that goblins or dwarves carved the tunnels, hence their small size.

Some anthropologists wonder if the tunnels were a burial ground or a physical interpretation of purgatory, a realm where souls are purified before entering Heaven.

Paleo-burrows?

Some Redditors and YouTubers believe the tunnels are paleo-burrows, underground shelters created by mega-fauna in the Pleistocene Epoch (2.6 million to 11,700 years ago). They think animals like giant sloths and armadillos dug these tunnels. However, though paleo-burrows do exist in South America, they are much wider (up to two meters in diameter) and usually feature claw marks and animal bones.

Visiting an erdstall

Erdstalls are not usually open to the public as they pose a hazard. Inexperienced cave explorers can get stuck, suffocate, or drown when the tunnels flood during the winter. However, innkeeper Vinzenz Wosner in northern Austria takes tourists on a “guided crawl” through the erdstalls on his land.