After four years of COVID closures, the north side of Everest is finally open this season to foreign expeditions. Among the limited number of teams granted a climbing permit is Alpenglow Expeditions, led by American climber and skier Adrian Ballinger, who couldn’t be happier to be back on what he considers the safest side of Everest by far.

This spring will be Ballinger‘s 6th time on the North Side of Everest and his 13th time on the mountain. Who better to share the details of the route with us!

The Alpenglow summit team will have 7 clients, 5 guides, and 14 sherpa climbers.

Context: Why the North Side is safer

Ballinger has guided in the Himalaya since the 1990s. The first time he planned to climb Everest from the North Side was in 2008, but the Chinese decided to close the mountain in order to take the Olympic torch to the summit without any outside disturbance. That forced everyone else to go to the South Side.

So Ballinger learned to guide Everest via the South Side between 2008 and 2014. It taught him a lot. He crossed the Khumbu Icefall 31 times, nearly died there twice, and learned about both the bright side and the shadows of the quickly growing business on the Nepalese side.

All this time, he was looking forward to trying the North Side, but his clients found the South Side more appealing. Then in 2015, a lethal avalanche from the West Shoulder killed 16 sherpas. It solidified Ballinger’s feelings that the North Side was safer. From then on, it was the North Side or nothing.

Adrian Ballinger at 8600m below the Second Step. Photo: Esteban Mena

No avalanches

“To begin with, the North Side route follows ridges, so anything falling down the mountain falls away from the climbers, while the South Side route follows valleys, so when something falls down, it falls on the climbers.”

Ballinger also remarks that the Khumbu Icefall is dangerous for everyone, but most of all for workers who must cross it several times.

“That is something I cannot do to the people working for us,” he says. “There is no way to ensure zero risk on high mountains, but the Khumbu Icefall is so obviously risky… My ethical responsibility as a for-profit company manager and mountain guide is to make the right decision.”

In the four years that the North Side was closed, Alpenglow teams have climbed other 8,000’ers, such as Makalu and Manaslu, or did other, lower peaks rather than deal with the Khumbu Icefall.

Tougher rules in Tibet

The CTMA (China-Tibet Mountaineering Association) has set strict limitations on the number of climbers on the mountain and the previous experience they require. They must have reached 7,000m before attempting Everest. There is also a mandatory 1:1 client-high altitude worker ratio.

To Ballinger, that also contributes to higher safety standards. Currently, there are also environmental protocols, such as strict waste management and a prohibition against diesel generators.

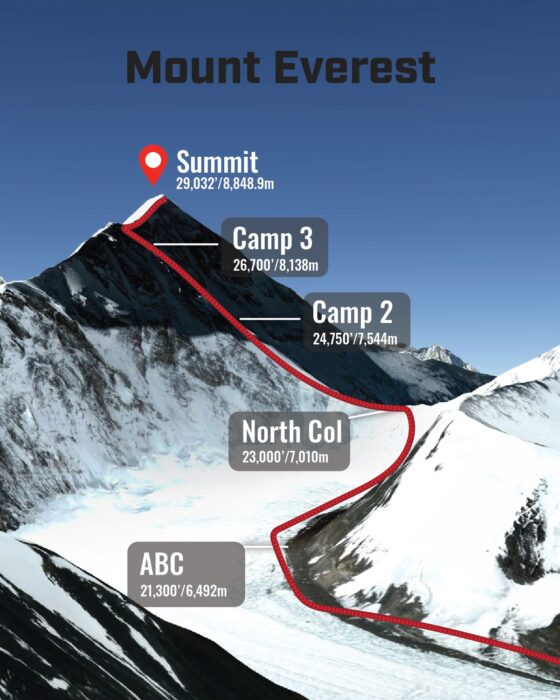

Everest North Side normal route: the NE Ridge

Everest Northeast Ridge route topo by Alpenglow Expeditions

Approach to Base Camp (5,500m)

Here comes the first surprise. You don’t trek to Everest Base Camp in Tibet. You drive.

For Ballinger, interestingly, this is a positive. It is a fast, clean way to get straight to the point of the trip.

“Even for clients on Nepal peaks, I do not recommend they trek to Base Camp. Instead, train at home with hypoxic tents and then get a helicopter airlift as close to BC as possible,” he said.

In Tibet, the already acclimatized clients meet in Chengdu. There, they fly to Lhasa and then drive for two or three days on a well-paved road across the Tibetan plateau. They stay in good hotels, visit some monasteries, and reach Base Camp within a week of leaving home.

The first acclimatization hikes take place from BC before moving to Advanced Base Camp.

Climbers stroll near Everest Base Camp in Tibet. Photo: Alpenglow Expeditions

BC to Advanced Base Camp (6,492m)

Climbers usually spend five to seven nights in Base Camp. They day hike to over 6,000m in sneakers on easy trails. Thus, they acclimatized while being treated to all kinds of comforts in BC, thanks to easy access by trucks instead of yaks and porters.

Once ready, the climbers move to Advanced Base Camp. Here, ABC feels more like Base Camp on the South Side. It’s on the edge of a glacier, and everything must be carried there on yaks.

The difference is that this ABC is slightly higher than Camp 2 on the South Side! Again, one can move around in sneakers, enjoying fresh food, heaters, and a fast internet connection while getting excellent acclimatization.

“That acclimatization, together with comfort, may be the main reason for the high rate of summit success, especially for no-O2 climbers,” said Ballinger.

The first trip from BC to ABC often features a one to two-night stay in an intermediate camp. “[It’s] a simple mountain camp, but it helps us make the 25km trip at a slower pace if needed,” Ballinger said.

Everest’s Base Camp on the North Side in 2019, the last time the mountain was open to foreign expeditions. Photo: Alpenglow Expeditions

Getting to ABC comprises the first round of acclimatization for commercial teams, whose members then return to Base Camp. “There are exceptions, of course, for very well-acclimatized climbers or in case a great weather window opens early in the season,” Ballinger said.

ABC (6,492m) to Camp 1 (7,000m): The North Col

Half an hour from ABC, the glacier begins, and the walking turns into mountaineering. Sneakers give way to mountain boots, crampons, and harnesses. Across the glacier, the route reaches the foot of the face leading to the huge North Col, where Camp 1 sits.

“The wall is similar to the Lhotse Face on the South Side,” Ballinger said. “Sometimes it’s all snow and quite easy, other times it has some ice and turns more technical. It’s never blue ice as on the Lhotse Face, but you can consider it real climbing.”

On the way to ABC. Photo: Alpenglow Expeditions

One must be aware of some seracs along the way, although Ballinger himself has never seen ice fall from these seracs.

“One year, I saw a ladder across a big crevasse, but the section can be safely done with only fixed ropes.”

Among seracs on the way to Camp 1. Photo: Alpenglow Expeditions

The trip from ABC to Camp 1 takes two to six hours. Camp 1 is huge but also very windy, a real mountain high camp.

“It also has an incredible view of the entire route above,” Ballinger said. It is in a very safe locale and high enough to be a great acclimatization destination.

Carla Pérez, Caroline Gleich, and another team member at C1. Photo: Carla Perez

The goal for climbers is to spend a night there without supplemental oxygen, says Ballinger, although some may choose not to overnight on their first rotation to 7,000m.

If one is fit enough, the best option is to climb higher, up the easy snow ramp that goes from Camp 1 to 7,400m, then return to ABC, ready for the summit push.

Above Camp 1. Photo: Alpenglow Expeditions

It is noteworthy that when the climbers return to Camp 1, preparing to move toward the summit, they will overnight there, sleeping on oxygen. From there, they are on bottled oxygen all the way to the top.

Camp 1 (7,000m) to Camp 2 (7,544m)

The previously mentioned snow ramp goes from Camp 1 to 7,400m, more than halfway to Camp 2. The slope is 20-30º and fixed with ropes. From that point, the terrain is windswept and mostly rocky, although it depends on the season.

Still, climbers wear crampons and go up another 200 vertical meters until Camp 2. It can get really windy there so it’s wise to check conditions before venturing on that part of the ridge, Ballinger notes. The move can take some four hours — six for those without supplemental O2.

Camp 2 spreads over a wide area, and the tents are pitched just under 7,600m to 7,800m.

Photo: Chad Peel

Camp 2 (7,544m) to Camp 3 (8,300m)

Climbers on oxygen will only go to Camp 3 on their summit push. No-O2 climbers typically need to reach 8,000m before their final push, so they go at least part of the way to Camp 3.

The trail involves scrambling up a rocky ridge, then a huge traverse across the side of the mountain at some 8,000m. Known as “The Sidewalk”, that section puts you right under the formidable North Face of Everest. The route then goes straight up the face again, on 30-35º snow, until Camp 3.

The Sidewalk, at 8,000m. Photo: Jaime Avila

For no-O2 climbers, it is a slow eight-hour day at a very high altitude. For oxygen-assisted climbers, it requires one bottle of oxygen and involves no particular difficulties except for altitude. It can be done in some four hours.

On the way to Camp 3 on Everest in 2019. Photo: Alpenglow Expeditions

Camp 3 is the highest camp on the mountain. Years ago, it was called Camp 4, because there was usually another camp between Camp 1 and Camp 2, but no one uses that anymore.

Camp 3 is 300m higher than the last camp on the South Side (Camp 4, located on the South Col). This is a great advantage for O2-assisted climbers, Ballinger notes.

“It makes for a shorter summit day and provides extra safety to have a camp so high up during the descent,” he said. “We make sure to supply Camp 3 with lots of extra oxygen and usually leave sherpas there to have hot drinks ready or serve as a backup in case of any trouble.”

Photo: Zeb Blais

It is not exactly comfy: None of the tents are level. On the other hand, it is safe, with no overhead hazards, but it is a very high, wild place.

“For no-O2 climbs, I find Camp 3 is quite challenging,” Ballinger said. “Climbers without supplementary oxygen usually don’t sleep there, since it is too high. Instead, they leave from Camp 2 in the afternoon, in order to get some warm hours. Then they stop at Camp 3 to rehydrate and rest, before leaving for the summit at around 9 pm.

“At least, that is what I did,” Ballinger said.

Camp 3 (8,300m) to summit (8,849m)

The summit push from Camp 3 treads on mountaineering history. Climbers follow the footsteps of Mallory and Irvine during their ill-fated 1924 climb.

“It’s incredible to see the famous three Steps, where the pioneers spent their last hours, wondering how far they got or if they ever reached the summit,” Ballinger said.

Although the route is completely fixed, it remains challenging.

Sunrise at the top of the world. Photo: Alpenglow Expeditions

“Unlike the South Side, the final push on the North Side alternates short, steep sections with flats,” he said. “The terrain is partly snow and occasionally low-angled rock as you progress under the ridge and continue on top of the ridge. Then there are the so-called Steps, the three steep rock bands that provide the most technical climbing of the entire route.”

Alpenglow team near the summit in the traverse around the white pyramid at 8750m. Photo: Esteban Mena.

The Steps

Here is Adrian Ballinger’s description of the crux of the Everest North Side route:

The First Step is all rock climbing with a fixed rope. it is a low-angled slab but it feels like real rock climbing. [Surmounting] this step gets you on top of the ridge, an amazing place with the North Face on one side and the Kangsung Face on the other side. And you get there as the sun rises. The views are just unreal!”

Summit day. Photo: Carla Perez

The Second Step is the most famous because of the ladders, installed every year by Chinese-Tibetan climbers. We also have some extra fixed ropes as backup, to avoid traffic jams in that area.

Without the ladders, the Second Step would be a 5.10 (5+, 6- in French grades) and it feels almost vertical. It would be very hard to climb without ladders at that altitude. It is short but intense and rewarding when you get to the top of it. Then some easy, flattish terrain follows until the Third Step.

The Third Step is like a chimney gully through a rock band. There are no ladders there, but of course, it’s all fixed. (The entire route is fixed from ABC to the summit.) It is not as difficult as the Second Step but it is very high up and it really slows people down.

After overcoming it, climbers have a wild traverse on a ledge system down to the North Face. They then zigzag back to the ridge and the final summit. Imagining the progression on that wild terrain in the 1920s without ropes is sensational.

Urken Sherpa on the summit of Everest, 2018. Photo: Topo Mena.

Overall, it is a shorter and less steep summit day on the North Side than on the South Side.

Also, with about one-fifth the number of climbers, it’s a quiet summit push compared to the South Side.

“There are rarely lines if you pick your summit day well, and the climb is quiet until you get to the top and meet a lot of climbers from the South Side,” Ballinger said. “Then you turn around, leave the summit chaos, and descend quietly again.”

Carla Perez, without oxygen on top of Everest, 2019, with Caroline Gleich in 2019. Photo: Rob Lea

Ballinger estimates that there will be 200 people (including foreigners, sherpas, and guides) on the North Side of Everest this year.

The descent

“The trip from Camp 3 to the summit can take four to six hours for climbers on oxygen,” Ballinger said. “But the descent is long. Attention is required on the three Steps, which must be rappeled down.”

Ballinger notes that since the terrain is not as snowy and steep as on the South Side, expeditions must have plenty of human power, oxygen, and resources if a climber has an issue, whether a twisted ankle or Acute Mountain Sickness, because dragging them down through the snow is not an option.

High camp on the North side of Everest. Photo: Jaime Avila

The good news is that, once the Steps are over, the descent is quick and straightforward. Ballinger remarks that he tries to ensure that team members never, ever have to spend a second night in Camp 3.

“It would be okay with enough oxygen, but clients will be much safer and better if they make it lower down,” he said.

The vast majority make it all the way down to the North Col that day. Some may stop for the night in Camp 2, and then about 20 percent of them go all the way down to ABC. The reward is great tents, sneakers — and a chef!