Christian Spain was under assault. In 711 AD, invading Muslim forces defeated Roderic, the last of the Visigothic kings, at the Battle of Guadalete. Amid the chaos, several bishops and their followers traversed the perilous Atlantic in search of a new home. Antillia began to appear on nautical maps, beckoning explorers to a rich, Christian utopia whose inhabitants wanted for nothing.

What’s in a name?

The very name Antillia breeds confusion. The word “Antilles” refers to the Caribbean Islands. To the north are the Greater Antilles (Cuba, Haiti, Dominican Republic, Jamaica, and Puerto Rico), and to the south are the Lesser Antilles (from the Virgin Islands to Trinidad and Tobago). Antilles may have originated from Antillia, and over the centuries, the spelling of the name changed.

Antillia first appeared in 1367 on a nautical chart created by Venetian brothers Domenico and Francesco Pizzigano. The chart was advanced for its time, providing some measure of accuracy for sailors. The map did not focus on the interior of discovered lands, but rather on their locations. Ironically, the map depicted several imaginary Atlantic islands such as the Isles of the Blessed, Hy-Brasil, Mayda, and Saint Brendan’s Island. Though Antillia is not pinpointed on the map, the text mentions it: “statues on the shores of Atuilla.”

In 1424, Zuane Pizzigano, a relative of the Pizzigano brothers, produced a chart and placed Antillia slightly beyond the Azores. The island looks rectangular and is accompanied by other islands called Satanzes, Ymana, and Saya, forming an archipelago.

The mysterious island eventually appeared on Martin Behaim’s 1492 Erdapfel, the world’s oldest surviving globe. As we know, Christopher Columbus discovered the Americas in 1492. However, his discoveries were not reported until 1493, and the Americas were not included on the globe. Yet there are several phantom islands, including Antillia.

Historical backing

According to legend, Antillia was a Christian haven during a time of upheaval. In the 8th century, the reign of the Visigothic kings in Spain was coming to an end. The Umayyad Caliphate struck the heart of Visigothic rule in Toledo, and the surrounding Christian kingdoms fell like dominoes.

On Martin Behaim’s 1492 Nuremberg globe, it states:

In the year 734 of Christ, when the world of Spain had been won by the heathen Moors of Africa, the above island Antillia, called Septe Citade, was inhabited by an archbishop from Porto in Portugal, with six other bishops, and other Christians, men and women, who had fled thither from Spain, by ship, together with their cattle, belongings and goods.

In the 16th century, Spanish cartographer Pedro de Medina elaborated:

There are on Antillia people who speak the language of Spain, that of the king Don Rodrigo, last of the Gothic kings of Spain. When the barbarians entered Spain, it is believed that to this island he fled. This island has an Archbishop and six bishops, each one has his own city, because of so many, it was called the island of Seven Cities.

The island supposedly featured seven settlements led by seven bishops, which were Aira, Ansalli, Antuab, Ansesseli, Ansodi, Ansoll, and Con.

Writer Jerald Fritzinger, author of Pre-Columbian Trans-Oceanic Contact, suggests a possible connection between the Antillia myth and a real Visigothic figure named Sacaru. According to Fritzinger, Sacaru took his fleet and other refugees to the Canary Islands after a Muslim attack. We can find evidence for this in the writings of the 17th-century Portuguese historian and poet Manuel de Faria e Sousa. The Portuguese historian claimed Sacaru found an Atlantic island “populated by Portuguese, which has seven cities.”

Historian George E. Buker, who wrote The Search for the Seven Cities and Early American Exploration, detailed a variation of the story that describes a bishop ordering the burning of the ships after settling on Antillia.

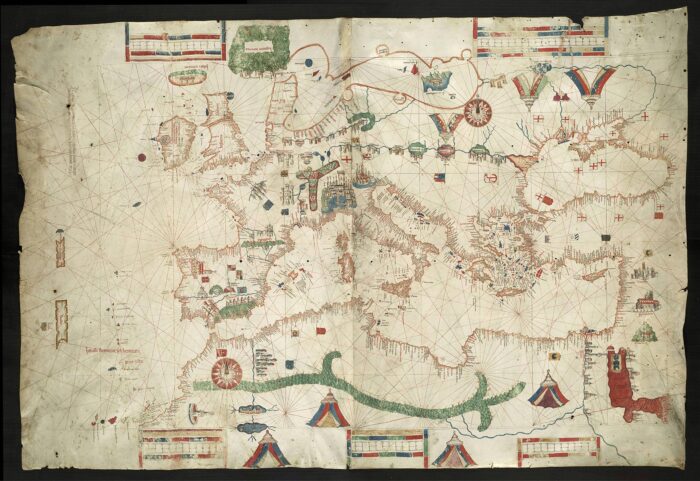

An early nautical chart shows Antillia to the west of Iberia. Photo: Albino de Canepa

Theories

Despite these references, there are no accounts of explorers setting foot on Antillia’s shores, and details of the story change between accounts. During the Age of Discovery, explorers often used mythical cities to convince Christian monarchs to fund their expeditions. But it wasn’t long before the legend of Antillia and its seven cities moved to the New World.

There seems to be an overlap between the myths of the Seven Cities of Antilia and the Seven Cities of Cíbola. Cíbola is the name given to one of the legendary Seven Cities of Gold, a Spanish obsession in the 16th century. Cíbola was supposedly a fabulously wealthy city somewhere in the unexplored lands north of New Spain (modern-day Mexico).

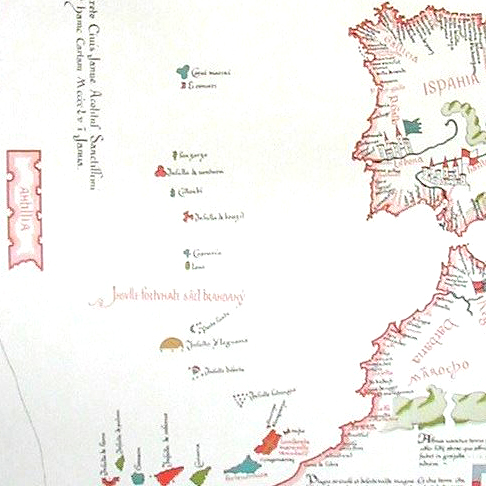

Map of Antillia and other islands. Photo: Bartolomeo Pareto

Rumors of other golden cities sprang up across the Caribbean and South America. Eventually, explorers began to call the Caribbean islands the Antilles, perhaps to persuade their benefactors in Europe to fund further exploration in the hope of finding gold.

Another theory is that Antillia could refer to the Azores and Madeira. Yet, on the 1424 chart and subsequent maps, Antillia was separate from the Azores.

The Savage Islands

There is another candidate. The Savage Islands are an archipelago 280km south of Madeira and 165km north of the Canaries. These islands have been mostly uninhabited since their discovery by explorer Diogo Gomes de Sintra in 1438. Settlement began in the 15th century. However, is it possible that a small group of people fleeing the Moors found refuge here? If so, they left no archaeological evidence.

A final theory points out the similarities between the shape of Antillia on early maps and the shape of Portugal. They are both rectangular, and their people speak Portuguese. Some medieval historians believed the New World reflected the Old World, the concept of “Harmonia Mundi.” Therefore, Antillia might have represented an extension of Portugal, a made-up island to inspire hope that a part of Christian Portugal had not fallen to the Moors. Or perhaps it was an invention to persuade faithful Christians to abandon Moorish Iberia.